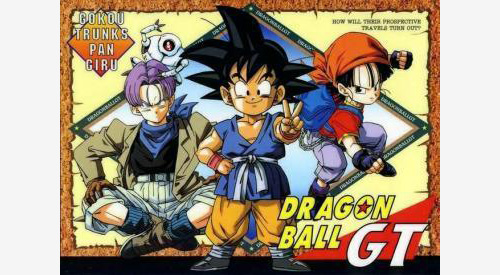

Dragon Ball GT Music – Composer Mark Menza Interview Part 1

American Dragon Ball GT. What do those words immediately make you think of? If it’s the controversial rap music intro, then today you’re in for a treat because I recently interviewed Mark Menza, the composer of FUNimation’s Dragon Ball GT.

Today you’ll discover how Mark earned the job working on GT, the challenges he faced, his musical influences, and what he thinks about Dragon Ball fans.

This article is for the hardcore Dragon Ball fan that wants all the details they’ve been missing since GT went off the airwaves.

You’ll learn exactly why GT ended up the way it did and discover the true story of GT’s development.

Dragon Ball Music and Mark Menza

Derek: Thanks for taking the time to speak with me.

Many Dragon Ball fans have stated that they love the American music, while as I’m sure you know, others have said they prefer the original Japanese. The Dragon Ball GT soundtrack is particularly controversial and still heavily discussed by fans 9 years after it was composed, so I thought who better to discuss this with than the composer himself!

Mark: There you go!

Derek: A lot of fans are interested in learning about the production and history of Dragon Ball’s music in the United States. Some of the questions here are from your fans that would like to know more about you and your Dragon Ball GT music.

Do you have any questions for me before we begin?

Mark: No, I read a little bit of your blog which was very interesting. I’m sort of surprised, maybe it’s more of an observation, that there’s still this huge interest in the show that has essentially been off the air for so long, particularly in Japan. I find it interesting that there is still this huge audience for it. It’s rather amazing.

Derek: I completely agree. People are still obsessed with Dragon Ball, and everybody wants a new series, but there isn’t one so they keep talking about the existing content.

And that is what brings us to our topic today, which is Dragon Ball GT.

First let me mention your background for a moment to introduce the reader to your experience.

You graduated from State University New York at Fredonia with a bachelor’s in music, correct?

Mark: Correct.

Derek: You taught guitar and Jazz from Brookhaven from 1989 to 1993. And then you opened your studio, Menza Music, in 1994, with a focus on scoring pictures. You’ve been doing it for 18 years and have worked on a number of documentary films, web media, and anime series, earning numerous awards.

Mark: Right. Actually, the reason I ended up working on GT was because I was in Dallas, in the area where they produced it. I came here to go to UNT (University of North Texas) and worked on my Masters for 4 years in Compositional Theory. So I was really here to write music.

I worked on other children’s properties; I worked on a show for PBS called Wishbone in the mid 90’s. I think that’s how I got involved with it. That was fun because we had a live, full orchestra to record, and we recorded some of it in Dallas and some of it in Seattle.

Then I worked on and scored the original pilot for Jimmy Neutron on Nickelodeon. I worked on that as the Audio Post Supervisor.

I started to write music for them and then Nickelodeon, the producers… and this applies to Dragon Ball as well, the producers really dictate what goes on.

Some of the other composers I’ve run into, we all sort of joke about this…

It’s always kind of amusing when the fans are like, “What have you done with our music?!” or “What were you thinking here?!” It’s like, “Agh, I don’t know, I didn’t really think about it. I did what I was told.”

Not that we’re robots, but on any project, whether it’s a film, TV show or even something simple like a commercial, the producers have really strong dictates about what they want. They’ll play all these things for you and say, “Can you make the music like this?”

Probably the most famous is the rap intro to GT, that people got…

Derek: Well, hold on, I’m going to ask you about that in a moment.

A Musician at a Young Age

Derek: Let me first ask, why did you get into music, and what type of music influences you the most?

Mark: I started playing and studying when I was 8 years old. I studied classical guitar as a teenager, about 13, 14, and 15. I studied with a guy name Michael Andriaccio at the University of Buffalo, which was a great privilege. My parents were a friend of the family and knew somebody who knew him. So he had a big influence on me, as well as several teachers growing up.

And of course all the music of the 70’s and 80’s was a huge influence, the Pop music for me and then later Jazz, probably the greatest influence, which you find in GT as well, is the Jazz idiom.

Derek: I noticed that.

Mark: Yeah, from the traditional stuff. Whenever I could sneak a hint of that in harmonically, I would. You never hear a jazz theme necessarily. I mean, rarely if ever did that show up in the GT landscape, but a lot of the harmony that went into it is probably more indicative of Jazz harmonies, such as moving tonal centers and keys changing around, that’s part of everything I write, and I think that comes from Jazz.

So to answer your question about what influences me, it’s always been the jazz tradition.

There have always been a lot of musicians in my family. I have a cousin named Don Menza, who is really known in the jazz world, and saxophone. If you Google him you’ll get hundreds of thousands of hits. An amazing player. Used to be on The Tonight Show. Toured with Buddy Rich for 10 years, which was almost unheard of if you know anything of the Buddy Rich era.

Derek: Unfortunately I don’t.

Don still lives in North Hollywood, he’s retired now. His son is Nick Menza, the one-time drummer for Megadeath. Nick is pretty well known in the heavy metal world.

Derek: So this is really in your family, then.

Mark: Yeah, and on that same side of the Menza family, there’s another drummer who lives in Ventura who was out with the Wallflowers for 7 years. His name is Mario Calire and he is my first cousin once removed. They opened for Tom Petty for years, and he’s now the host of Ozomatli. They’re a wild band. He toured with Liz Phair and they’ve gone all over the world. His dad, Jimmy Calire was a keyboard player and a cousin of mine.

All of that had an influence on me growing up. I would go and watch my uncles play in the garage, in orchestras. That was always around me.

Derek: Wow, I can definitely see why you’re doing what you’re doing.

Getting on Board the Grand Tour

Derek: How did you end up working for FUNimation making anime music?

Mark: Barry Watson was a friend, I knew his wife who was a wonderful classical guitarist in the Dallas scene.

Derek: Barry was a producer at FUNimation, correct?

Mark: Yes, with Gen Fukunaga [the founder and CEO of FUNimation] and all those guys, when it was that generation of FUNimation.

So, Barry I knew personally, and one day he said, “Hey man, would you ever be interested in this other series we’re doing?” I said, “Sure! That sounds like a ton of fun, I would love to work on something like that.”

And I didn’t really know a lot about anime, and I knew only peripherally about Dragon Ball Z. When that was going on I was really heavily into Wishbone and right after that, Jimmy Neutron. I didn’t grow up with anime. Age wise I missed that. When Dragon Ball Z came to this country and was popular, I was already out of school, teaching Jazz and being a studio musician, that kind of thing, so I didn’t really know it.

Derek: Yeah, in an interview in Wizard Anime Insider magazine, Gen Fukunaga said, “If you think you know Dragon Ball GT, just wait! Nobody has done Dragon Ball GT like we have.”

Mark: Yeah, and you’ve got to know some of that is going to be marketing speak, although I think he really did believe that. I think I only met Gen twice, and it was during big events. It was like, “Hey, nice work!” He was always very nice to me and I didn’t really know anything about him until much later.

And Barry, I still talk to Barry every now and again, and he’s entirely out of the business now. He got me involved with it, to answer the question. He was the guy that knew me, knew what I did, had been to my studio, knew that I worked on animation and kids stuff, and thought I would be a good fit.

Derek: So there was no audition process, you were hand-picked?

Mark: If there was an audition to speak of, it was that I helped score one of the Dragon Ball Z features, and he really liked that. I think it was Return of Cooler.

It’s like, “Wow, I’ve got to go back and watch all of them!” Which I did, I watched some of the stuff. I didn’t invest a tremendous amount of time because of time constraints.

Derek: It’s a huge series.

Mark: Right. It’s a huge saga, all of it! And I loved all the music that I heard, from the guys who did it here to the original stuff in Japan, that was all interesting.

I could see how FUNimation wanted to change it, and I scored in total, I think, seven Dragon Ball Z features, either in part or in whole, and then one GT feature much later on. Broly I did, and the others I can’t even remember the names of them now.

A lot of the times they had working titles, and only 6 months later I would finally see them for sale on the internet and I’d be like, “Oh, they called it that? Interesting!” So that’s why I don’t remember the names, because I had all these working titles.

So I had done these for maybe a year, a year and a half. I would do one, then I wouldn’t talk to Barry for a few months, then I’d do another, and so on.

Then he came to me with GT and pitched that idea. We came up with a deal, a contract, and away we went.

Derek: Wow, alright, very interesting. Nobody knew that story, so that’s a brand new exclusive. It had always been a mystery, so thank you very much for clearing that up.

You were only vaguely familiar with Dragon Ball before you got the project, but were you aware of the fandom behind Dragon Ball when you went into it?

Mark: You know, my understanding, as limited as it was, was that it was a show that was well known in Japan.

Making the Music

Derek: You mentioned that you did listen to some of the Dragon Ball music. I had heard that you were specifically advised by the FUNimation producers to not listen to the DBZ soundtrack AT ALL. Is that correct?

Mark: I don’t know that anybody ever told me that. They did say, “Mark, don’t pay any attention to what’s come before, because we really want to take it in a new direction.” But I don’t think anybody said don’t listen to it because you don’t want to be influenced.

From time to time they would give me notes. The way all composers work is that somebody pitches the project to you, or in this case there’s an existing piece that has a legacy, so you can immediately see the picture. They send you the scripts and you can watch the finished product, which doesn’t happen on newer shows where it’s often a work in-progress. It was a little unusual to see a completed show where you could watch the show before it and even the show after it! Sort of wrap your arms around the storyline.

So I said, “Okay, what kind of thing are you going for?” They would play some examples for me very early on, “What about this band, or this one?” They would send little samples, mp3’s, and honestly I’d be lying if I could tell you what they were. Here’s a clip of some heavy metal band, or some dark orchestral music from a game that they liked. They said, “Use that as a jumping off point because that’s kind of what we’re thinking. What do you think?”

I would take that and do part of an episode, first or second episode, and send it to them. They’d say, “Yeah, that’s good. Maybe more of this, less of that.” Though after about 5 or 6 episodes I never got any notes back. They were like, “This is great, keep going!” Of course we talked on a regular basis.

Like they’d say, “On episode 20 (or whatever) that’s coming up, there’s a new villain, try to come up with a theme for him.”

So I had, sort of, themes for all the characters, but I didn’t really, it wasn’t like, The Lord of the Rings things, where you had this leitmotif going on, which is this Wagnerian idea where you give each character a theme and every time you see this character you play his theme.

It’s almost too complicated in most instances to do that, because all of a sudden, 3 or 4 characters show up on the scene. Piccolo shows up at the same time a villain appears, and somebody else shows up, and then Vegeta shows up. Then all of a sudden you’re going, “Um, okay, this is going to be a musical mess.” I decided to go with a more overarching theme as we move through it.

Like, here’s the hero, something heroic happening, and all the heroes of the series. Then the villains were more transient, and they might show up for 3 to 8 episodes, and they might have a theme.

Derek: Like the Super 17 Theme.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FMiXWWMQw9w

Mark: Right, so those kinds of things would go on. But if you try to beat that to death, and be very literal with it, it gets goofy sounding to me. As a composer you have to figure out what’s working, and do that. So that was how the process worked and how I was introduced to it. I don’t remember anybody saying specifically don’t listen to this, that or the other thing.

My take on it, and some of this was influenced from what the guys at FUNimation were saying, is that GT would be for a much older American audience.

I think one of the main reasons they rescored the shows at all was that they found the fan base here, at least this is my understanding, was older here than it was in Japan. While at the same time that a Japanese 12 year old boy might be sort of, culturally, at a different place than a 12 year old kid here. So that 12 year old kid might be listening to what a 16, 17 or 18 year old might be listening to in Japan.

And a lot of the J-Pop stuff is very, almost what we used to call Bubble Gum music here. And I don’t mean that in a pejorative sense, I think it’s cool music and trust me, I write it, I’m involved in a lot of children’s music. I think that all that music fits for certain ages, and the idea with GT was they really wanted to, and I think FUNimation did this with all the stuff they worked on, they wanted to age it up, a little bit.

Not tremendously so, but when I compare it, at least in my ear, obviously fans who grew up listening to the original show, they’re going to tell you something completely different, but my ear, hearing the Japanese GT music for the very first time, the little bit I heard, it was like, “Oh, yeah, that’s definitely younger, sweeter, and in some cases kind of heartfelt.”

Derek: Yeah, more emotional.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PPAkg1ji6_E

Mark: Right, the Japanese wanted it more emotional. And I thought that was fine, but it seemed much younger than an American audience, and I think the pacing of it was much slower. It almost ran contrary to all the action on the screen. You had these very big, dramatic things going on, and sometimes the music was almost trying to be humorous, and I was going, “Wow, that doesn’t seem to work for me.”

Some of that may have been the translations, because I think the guys at FUNimation translated the script to make the characters older in how they talked and what they were saying, and how they interpreted the storyline. And I think they did the exact same thing with the music.

Derek: Yes, I would agree.

Mark: So that was the idea. The music was tougher sounding, and maybe a little grittier, and less sweeter.

[On second thought,] the Japanese was more emotional? Perhaps. I think it was simpler and more childlike in the original Japanese. Although I would be afraid to ever say that out loud because I think a lot of the fans really love it!

Derek: Yes, that’s exactly what they do.

Mark: And I totally get that. I would be the same way for The Simpsons, which I watch a lot of. If I had to watch The Simpsons dubbed in German and rescored with music more endemic to German culture, I might hate it compared to what Alf Clausen has done because to me that’s vintage Simpsons. Anything other than the Danny Elfman theme, to me, would make me crazy.

Making the GT Music

Derek: That leads me into the music itself. The GT soundtrack has big thumping bass guitar, heavy, grungy lead guitar riffs and a drum set backed by various effects. How would you describe this sound?

Mark: I think that’s sort of accurate. It was lots of layers of guitars. The themes were based around doing, kind of like the Evanesence thing, which was popular at the time. That may have also been something that was suggested to me. I listened to that very driving, very distorted guitar.

I had a guitar I had not used in years that I pulled out for the show. This white, custom made, Jackson guitar that Grover Jackson made for me years ago. It’s a very early serial number, a kind of collector’s item.

It’s a serious, heavy metal guitar. I pulled this thing out, dusted it off, and it went to work on GT. It was used almost exclusively. Big, etchy, loud, Jeff Beck pickup in the bridge position, for those people who are interested in that kind of stuff.

Derek: Yeah, there are people who would like to know these things.

Mark: It was a Seymour Duncan, Jeff Beck pickup that was series parallel and tapped. The guitar nutjobs will know what that’s all about. It means I can split the coils or I can shut one off and turn it into a single coil. All of this had a very specific guitar sound, so I was going for that specific guitar sound.

The reason that it gets to be so much is, probably the most challenging thing to do on GT was that they wanted it scored end to end. And I’ve never worked on another show that was scored end to end.

Derek: What does that mean?

Mark: There are two 11 minute segments that make up the 22 minute episode. When a piece of music starts at the beginning after the opening credit music finished and the episode began, it was a continuous piece of music for 11 minutes.

Derek: There was no silence?

Mark: Never! I mean, I would say…

You would be hard pressed to find a single movement in most symphonies that are 11 minutes long. Bach, maybe. Most symphonies have several movements that stop. It was very difficult to compose GT’s music because it was continuously in transition.

Derek: Why was that? Was that a direction from the producers?

Mark: Absolutely. Right from the get go! They felt like the show needed that level of pacing, because they couldn’t change the animation and they couldn’t make any new animation.

Which for me, on something like Jimmy Neutron, if you watch any other kid show aimed at the same demographic, say, anything on Nickelodeon or Cartoon Network, even something like Power Rangers, in a 22 minute episode you might have anywhere from between 8 to maybe 15 minutes of music. That would be a heavily scored show.

This was 22 minutes of music.

Derek: Every episode.

Mark: Yeah! Every episode. I got to where I was doing each show in about 3 days.

Derek: Wow, that takes a lot of work.

Mark: It was a stupid amount of work. But I had to do it that way for scheduling purposes, with everything else that I was doing and the schedule of GT.

In the beginning I would probably spend 10 days to 2 weeks on the first 2 or 3 episodes. But once I had a chunk of material to work off of, I would say, “Okay, I’m going to bring in this theme, I’m going to use this, and this and this, I’m going to play a new guitar line on top of it, so let me lay down this part.” And boom, if I could get 3 or 4 minutes a day, then I was excited.

Then when I got to where I could do 7 or 8 minutes a day, I was truckin’. And the continuous nature of it was REALLY challenging.

Derek: I bet. Did you have an assistant or staff that helped?

Mark: No. Not on this show. That was a budgetary constraint. I had to make it work by myself. When I worked on other shows I had audio post people, which I didn’t do on GT because FUNimation had their own in-house audio people, as that was primarily what they were doing. But they didn’t have in-house composers, necessarily.

They had audio engineers, dialogue coaches, and studios that were set up to record all of that dialogue. And that was a huge job, that ADR job of looping the picture and recording each line. Once these guys, the script writers, had written the show and figured out what they were going to do for each saga of the series, that was a tremendous job in and of itself.

Having an in-house composer is not a business model that makes sense. You can’t keep them busy everyday so you’re paying them lots of money and it makes no sense. And that’s the way most shows are done. The composer doesn’t work for the production company, he’s a separate entity.

When you’re talking about a film where they hire a famous composer like John Williams, or a TV show that’s on currently, like 30 Rock, that all goes out to a composer who is a guy like me who probably has his own studio, either in a facility like I do, or many of them even in their homes. I have a facility because I also do audio post production. I just didn’t do that on any of the stuff for FUNimation because they had their own sound effects editors and dialogue guys.

You asked about assistants. Usually I have assistants to help me out, other engineers to help me on the engineering side of things, and the sound effects and mixing side of things.

Derek: Were there synthetic instruments in the GT soundtrack as well?

Mark: The short answer to that is yes. A lot of it is strings samples. 90% of what you hear on TV, if you watch Law & Order, it’s all samples, they don’t hire a real orchestra anymore. They do on the Simpsons, interestingly enough. That is one of the few shows that has a 30 to 40 piece orchestra that they record each episode with. But that is a rarity. It’s a hold over. Most television shows, because of both the schedule and the budgets that have shrunk over the years, almost all of those are sampled strings. Meaning a live string section recorded into a sample library that go into these elaborate computers.

Derek: Through the keyboard.

Mark: Right. And they’re all virtual instruments in the computer, or I have stand alone sample players to play the strings, the brass, or the woodwinds.

As far as synth stuff goes in GT, all the bass was live, all the guitars were live, there was some actual acoustic mandolin that was recorded, some acoustic guitar, steel string and nylon string that was used. All of that I played, recorded and engineered myself.

Derek: That is fantastic. It’s amazing you did all that by yourself.

Let’s a take a break for a moment and then we’ll continue.

Conclusion of Part 1

Today you learned how Mark was chosen to be the composer for FUNimation’s version of Dragon Ball GT, how he composes music, and how he overcame the challenges of end to end music by working super hard, just like a Saiyan!

Continue reading Part 2 of the Mark Menza interview, where you’ll hear about Bruce Faulconer, corporate direction of GT’s music by FUNimation staff, the chances for a Dragon Ball GT album, and the origins of the infamous Dragon Ball GT rap intro!

For all you guitar lovers, Mark shared the specs with me on his white guitar:

Jackson Soloist:

Dinky Neck through body

Serial Number 0547

Kahler Vibrato with Palm bar

Seymour Duncan pickups:

2 Single coil are there 4 conductor that are wired in phase/out of phase with mine 3 way switches

Bridge is a Seymour Duncan Jeff Beck 4 conductor that is also wired to be Split/Series/Parallel [in phase/out of phase] with separate on/off

So, yeah, I’m not sure what that means, but there you go! :)

Man it has to be hard, and you can hear it in his vocabulary, to have worked so hard on something that ended up so controversial. There is a lot of hyperbole on the Internet and fans have really latched onto the name Menza in a negative way despite him being just a hired gun. I suppose it’s fortunate that the reception for GT is lukewarm in general so there isn’t any major resounding backlash like some of the other bone-headed calls FUNimation made in the past. Menza sounds like a very talented man! I rather enjoyed his scores for some of the Z movies and the theme song he did on the DBZ Season orange box sets.

Mark was really nice to talk with. Changed my whole perspective on the guy since I had always been a fan of the original Japanese. In Part 2 of the interview we discuss his response to the more hardcore fans.

Yeah, I had no idea it required so much effort to score the episodes. He’s right that it’s absolutely crazy to require end to end music. And then to have the fans be so angry at the finished product. If I were in the same position I think that would have hurt my confidence or emotions in a lot of ways.

I gotta know…. what were Funimation’s original working titles for the movies? I’d be very curious to know.

Let me ask him and see if I can find out.

UPDATE: Here was his response.

"I really don’t remember any of them. They were always short and just something we could refer to."

Awesome interview, Derek. I’ve always liked Menza’s music compared to Faulconer’s, and his jazz influences make a lot of sense to me. I’m surprised to here how much of the music influence for the show comes from the producers, but I don’t think I should be. Sort of changes my whole perspective on how and why certain things were done with DBZ/GT.

Also, it’s cathartic to see him talk about the lack of silence so incredulously. That has always irked me about the American DBZ/GT scores more than anything else – its obvious lack of subtly.

That said, Mark seems like a talented guy. I’ll be sure to keep this interview on-hand for the next time I see some fanboy bad mouthing him on the internet!

I agree completely about the silence. What’s funny is that even when I was 14 years old I noticed it and was put off. But I still watched the show everyday because it IS Dragon Ball after all. But then one day my dad was like, "It’s just constant noise." And that’s when I realized that yeah, it is constant.

Later as I did more research for the book I found out this was done on purpose. Gen Fukunaga said that according to American demographic studies, little kids need constant sound, otherwise they won’t pay attention to the TV. So it was completely a business decision in order to keep the children glued to the television set.

This ideology trickled down into every facet of American Dragon Ball Z and GT’s production, including the voice acting. That’s why they are like they are. Only in Dragon Ball did they use the original Japanese music, and that’s why there is silence. But of course the voice acting and direction still involves near constant sound, even when it’s uncalled for, such as grunting for no reason.

And please do share it with others! Facebook likes, Tweets and all that. :)

I think pretty much only the ending of DBGT really had any silence during the credits.

There was still an end credits theme:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jHIbjEkPQwM

If that’s what you were referring to.

Lol, I meant the ending ending. (ep 64) Can’t remember know for sure, but I remember it was very quiet then.

Btw, when’s part 2 coming up?

Ah, okay.

I’m working on a big website project for a client right now. I may be free by the end of tomorrow or the day after, but no guarantees. There’s a lot to do.

Glad to know you’re looking forward to it!

The music makes GT so much better!!

The darkness and intensity adds immense emotion to the show. My favorite music was from the Baby Saga. Great job!