Piccolo is Black is Not What You Think! – Book Review

Piccolo is Black is a good book, but it’s so disappointing!

That’s because in spite of the title, Piccolo is Black is not a book about Piccolo, nor Dragon Ball, and it’s not written for Dragon Ball fans, anime fans, pop culture experts, or any specific audience.

You shouldn’t read Piccolo is Black if you’re a Dragon Ball fan expecting to learn more about the series.

Instead, Piccolo is Black (aff) is a book about what it’s like to grow up as a black man in Detroit who was raised as a Seventh Day Adventist with hyper-religious parents, and who was influenced by the so-called black characters in the cartoons he was forbidden to watch.

In this regard, the book provides an eye-opening and conversation-starting perspective on life, trauma, and growth that everyone can benefit from reading.

But is that enough to save it for Dragon Ball fans?

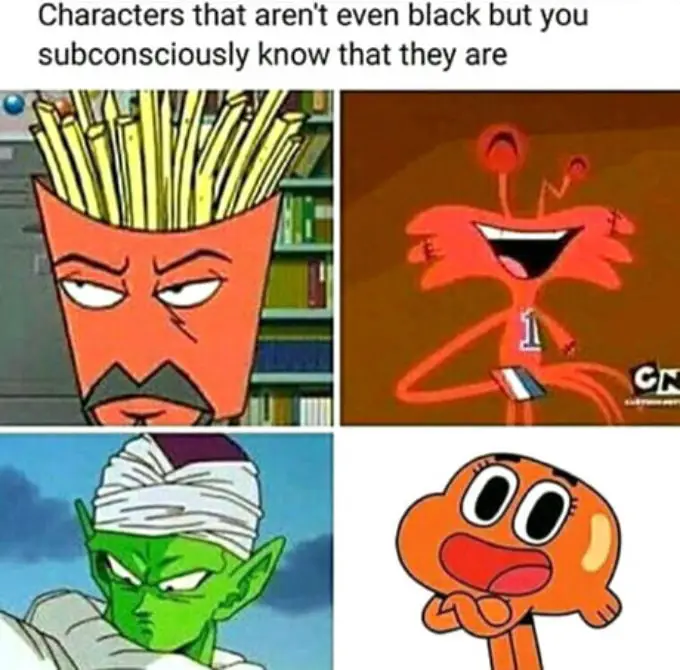

Piccolo is Black Meme

Jordan M. Calhoun is a New York-based Editor in Chief of Lifehacker and a contributing writer to The Atlantic.

Before I read Calhoun’s Piccolo is Black: A Memoir of Race, Religion, and Pop Culture (published by Lit Riot Press on April 26, 2022), I was intrigued by its title.

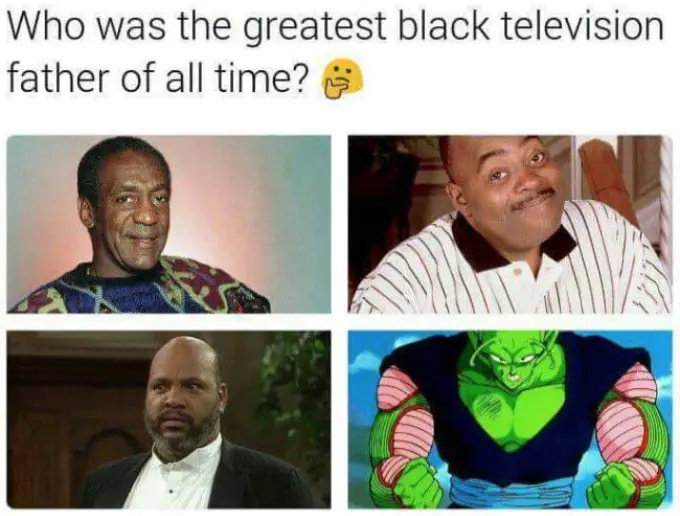

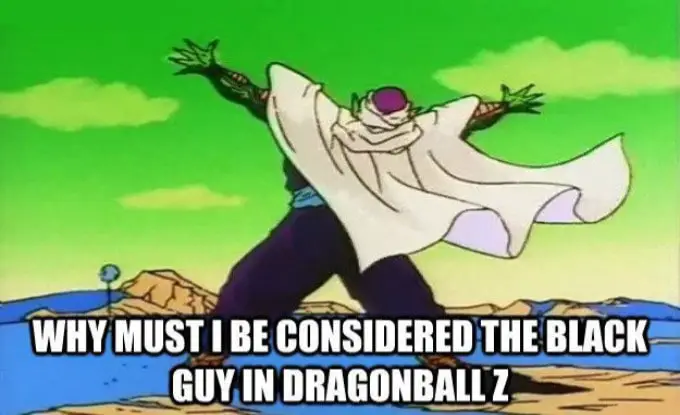

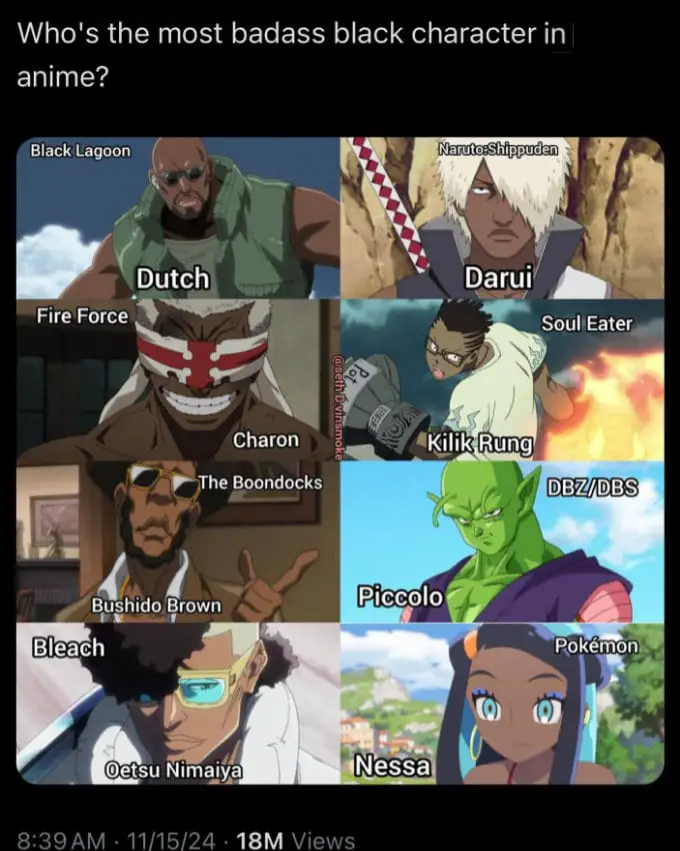

Dragon Ball fans are familiar with the meme that ‘Piccolo is black.’ It’s the idea that Piccolo, the green alien from the Planet Namek, is actually a black man.

Through the ‘Piccolo is black’ meme that originated in the early-2000s, English-speaking black men took an extraterrestrial bipedal slug man that was created by Dragon Ball’s Japanese author, Akira Toriyama, and appropriated him into Western culture.

How does the meme work? First, black fans noticed that Piccolo’s behavior aligned with black stereotypes as minorities in American society.

For example, he is a loner and misunderstood outsider who talks with a deep and gruff voice; comes from a struggling race that suffers from genocide by a white, land-owning tyrant; is masculine and quick to anger; and is a young and overbearing ‘parent’ who beats his ‘adopted son’ Gohan from another man’s baby mama in order to raise him well.

These stereotypes were then appropriated into comedic images with Piccolo and shared on an anonymous Internet.

They were also used as a tool for black racial empowerment and identification—as Piccolo is superhumanly strong, disciplined, and stoic.

After decades of the meme’s existence that continues to this day, the idea that ‘Piccolo is black’ has seeped into black culture and reached the point where most black fans I meet will chuckle at the joke, yet at the same time believe that Piccolo is indeed ‘the blackest’ main character in Dragon Ball—his green skin notwithstanding.

This sociological subtext of Piccolo’s ‘blackness’ among the fandom continues to be fueled by the on-going official Dragon Ball Super manga and anime. It’s here where Gohan’s daughter, Pan (who is Piccolo’s ‘granddaughter’), has a black female preschool teacher.

Even though Piccolo is asexual and no romance has been shown in their relationship, fans like to imagine that Piccolo should be dating this black woman because ‘Piccolo is black,’ and they make fan art showing them as a loving couple.

Or of Piccolo as a symbol of adoration for black woman in general.

So with the meme in mind, prior to reading the book, I wondered, will casual readers who are unfamiliar with anime read this book’s title and know who Piccolo is?

Conversely, will anime fans or fans of the meme read the book just because of the title?

And in either case, will this meme-based title be explained and elaborated on?

What is Piccolo is Black About?

I wanted Piccolo is Black to be an analysis of Dragon Ball’s culture, its social influence on black men in America, and how the author saw himself in Piccolo.

From my own experiences while growing up in the ‘90s, I already knew there weren’t many black characters in cartoons, so the book must be about how the author accepted Dragon Ball, in-part, because ‘Piccolo is black,’ and the positive effect this character had on him, right?

But after reading the intro and first three chapters, there was zero Dragon Ball content. Not even a mention of it until Chapter 4, where Calhoun describes watching Bible-based cartoons instead of the standard Saturday Morning cartoons that were forbidden in his home.

Here he makes a single-sentence analogy that Cell, a villain from Dragon Ball Z who taunts his opponents and waits for them to challenge him to a fight to the death, was analogous to Goliath, from the Biblical story of David and Goliath, who did likewise with the Philistines.

At first I was taken aback because Toriyama does not make such an analogy. But when I looked at Calhoun’s comparison from a Biblical perspective, and from the author’s eyes of a 12-year-old who was indoctrinated by religious stories, it became clear that he was comparing the pop culture that he enjoyed a few years later in life as a rebellious teenager to what his head was filled with as an obedient child. Pop culture overlapped with traditional culture.

That’s fine, except that’s where he stops. He gives no further analogies comparing David, to say, Gohan—as a smaller man who defeats Cell (the stronger giant)—and defends his people from a life of servitude or death. Nor any analysis about race, persecution, or the struggles of youth against the pressures thrust upon them by adults.

There’s no depth of thought.

Instead, what the Piccolo is Black book amounts to is Calhoun taking a particular subject, show, game, or film, summarizing a relevant section of it, and then talking about how it related to his development as a young man at the time he experienced it. For example, ‘here’s Transformers,’ ‘here’s Gargoyles,’ and so forth, with each one progressing his life story forward in a chronological order, from boy to young adult.

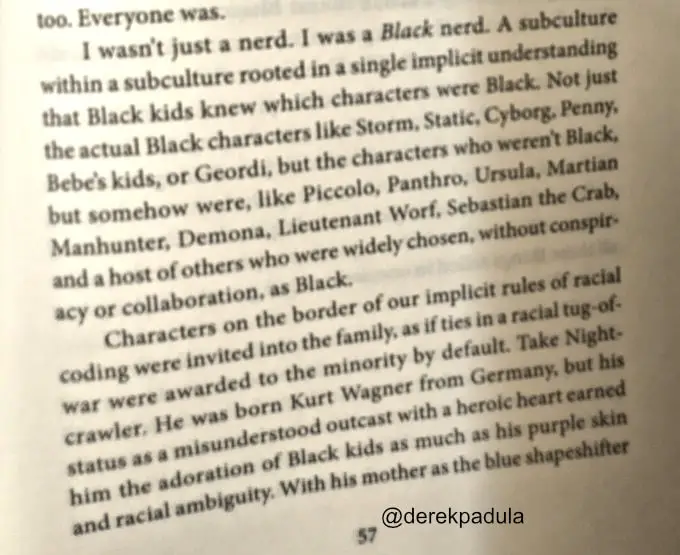

Yet it isn’t until page 57 when he finally touches on his thesis and title of the book, one quarter of the way through the text. He makes the argument that each cartoon, show, or movie he grew up with in the ‘90s has a single ‘black’ character in it, at a ratio of 1:5. They are the lonely man, the stoic, and the outsider who nevertheless is essential because he supports the others or holds the group together. Here, Piccolo is mentioned among many other non-black yet somehow black characters.

That’s when you understand what Calhoun is getting at with the title, not in an explicit statement, but by putting the pieces together, that these ‘black’ characters are an analogy for black people in general. He carries this argument for 4 pages and drops it at the end of the chapter.

Next, ‘here’s Robin Hood,’ ‘here’s Street Fighter II,’ continuing until the end.

Having detected this pattern and structure, I kept reading in the hopes of getting to Dragon Ball. I figured that once he was attending a public university, away from his well-meaning but discipline-obsessed parents and faculty, that he’d be free to watch Dragon Ball Z and discuss it in detail.

But he never gets to DBZ!

The book is titled after a Dragon Ball character, but there is no chapter dedicated to Dragon Ball or this character. Not even a full page.

Instead, you’ll receive an intriguing book about what it’s like to grow up as a black man in Detroit with divorced parents—and lack of a strong-but-compassionate father figure—and this boy’s traumatic experiences walking the line between devout and sinful, private and public, as he absorbed an increasing amount of pop culture. You’ll learn a lot about a life you didn’t live; which, to be fair, is the goal of a memoir.

Despite the superficial differences between us, I found Calhoun’s story relatable because I also grew up on television, in Michigan, and my parents were from Detroit.

Growing up in Grand Rapids, on the west side of the state, I often traveled to Detroit on the east side to visit my relatives for holidays and other events. And I grew up enjoying the same cartoons, video games, anime, and other forms of pop culture that Calhoun would eventually be able to experience. We even both attended Western Michigan University—at the same time. This delivered a feeling of nostalgia and affinity for this man I have never met.

And I often found myself coming across a new topic, term, or person I was unfamiliar with, and searching for it online to learn more about it before I continued to read. For example, the Seventh Day Adventist’s religious beliefs, which I found to be extreme, albeit admirable in principle (not execution).

But I’m still disappointed by the lack of Dragon Ball content.

Misleading Title

My initial concern about Piccolo is Black proved valid. It’s a misleading title that seems to be meant to pull in readers by capitalizing on the ‘Piccolo is black’ meme.

Dragon Ball is only mentioned in this book about 10 times across its 200 pages, with reference to a character’s name or quote, in a single sentence at a time.

Even with that aforementioned 4-page thesis on so-called black characters, 97.5% of the book’s page count (195 out of 200) has nothing to do with Piccolo or the series in which he’s found.

Calhoun says in his introduction and Acknowledgements section that his book is based on prior individual articles he had written for various websites, that he was then convinced by others to bring together and flesh out into a full memoir. He wrote it to express his feelings about the shows he grew up with, and his unique life experiences in relation to these shows.

That means he didn’t start with a strong thesis and then fill in the book with proof of his thesis; nor an intended audience.

As a result, it feels like a story where a bunch of stuff happens but you’re left wondering, ‘What was the point?’

To speculate, perhaps when the book was done and the publisher needed a title, someone chose the popular meme of ‘Piccolo is Black’ in order to entice you to read it.

I can’t blame them for wanting to sell copies, but the title feels disingenuous when you never come across an in-depth discussion of Dragon Ball or the titular Piccolo.

I’m no stranger to using memes in a title, as you’ll find in my Dragon Ball Z “It’s Over 9,000!” When Worldviews Collide book. But my book begins with this topic of the “It’s Over 9,000!” meme, analyzes it, and ends with it.

And while I use the meme to attract readers, I also use it as a vehicle to explore a psychological analysis of Dragon Ball’s main characters and how their upbringing shapes their views of each other, our views of them, and of how we view real-life people through the ideas that Akira Toriyama imparted to us through Dragon Ball. So, by the end of the book, you know why the meme is in the title.

Piccolo is Black doesn’t do that. It’s a title to get your attention, chuckle while thinking of the meme, and think, ‘Hm? What’s this book about?’

After finishing Piccolo is Black, I can see what Calhoun is alluding to. I understand his message through the dozens of references he makes to various programs and how they reflect his experiences growing up as a black man. But he doesn’t make this point by stating it, and instead leaves it up to the reader to connect the dots.

He never even explains the meme or why he chose this title. I just explained the meme in this book review, so why couldn’t he have done the same in the actual book? I guess he figured that you’ll get it through repetition, or assumed you already know it based on you being in his target demographic.

This leads me to conclude that Piccolo is Black: A Memoir of Race, Religion, and Pop Culture is actually about the sub-title, not the title.

As a result, the title is a double-edged sword.

After Akira Toriyama’s death on March 1, 2024, Calhoun was interviewed by Slate magazine to discuss Dragon Ball’s positive effect on black fans. He told them, “I was pretty young when I realized that recognizing black-coded characters is a shared cultural experience,” and “I didn’t have the academic language for it … but me and my friends just knew that Piccolo was black.”

I wish the book focused more on exploring this idea, instead of others.

Is Piccolo is Black Worth Reading?

Piccolo is Black has an identity crisis, much like the author does over the course of the book. It’s not for Dragon Ball fans. It’s not for casual anime or pop culture fans—unless you grew up watching the dozen-or-so series he discusses. And it’s not for religious people—although post-religious readers could find it cathartic.

In addition to this lack of focus, there are occasional typos and repetition, a too-casual use of swear words, stories of parental abuse, and graphic descriptions of masturbation; all of which may limit its audience.

There’s also no index, which bothers me as a non-fiction author. This made it harder for me to write this review because I couldn’t search the book for all instances of “Piccolo” or “Dragon Ball”.

Nevertheless, I recommend reading Piccolo is Black.

Calhoun does a good job of bringing you into his world and the experience of growing up under his difficult conditions. I felt a connection to the author due to our mutual experiences and interests. Likewise, empathy for his pain that was caused by other people—as any nerd can relate to. His story was enlightening, entertaining, and memorable, as a good memoir should be.

But I’m left with mixed feelings because of the misleading title.

Of course, if it weren’t for that title, I never would have read the book.

' . $comment->comment_content . '

'; } } else { echo 'No comments found.'; }