What Genre is Dragon Ball?

You might think you know Dragon Ball’s genre, but the real answer will surprise you.

I’ve been a fan of Dragon Ball since 1997, and I’ve seen Dragon Ball’s genre classified in dozens of different ways.

That’s why in this article I will use statistics, quotes, and facts to show you what genre Dragon Ball truly is.

Genre

Let’s start by defining the word ‘genre.’ I define genre as “a classification of artistic expression defined by a set of characteristics.”

We create genres to help us classify poetry, paintings, music, movies, literature, and other forms of artwork. For example, within cinema we have genres such as adventure, comedy, science fiction, romance, suspense, and horror.

Each of these genres has self-defining characteristics, which means comedy is different from romance. But if there are enough characteristics in the work that are shared among both genres, then you have a cross-genre of “romantic comedy.”

Genres help us categorize our world, but it can be difficult to classify a work of art when it falls into more than two genres at a time.

Such is the case with Dragon Ball. It’s not just an adventure story or a martial arts story, because as you’ll see, it has traits of both plus several others, such as action, comedy, and fantasy.

In addition, Dragon Ball’s genre changes at different points in the story, so it depends on when you examine it.

Official Genre

When being definitive, it’s important to return to the source. So rather than guess at the genre, I asked the official creators and localizers of the series for their answer. This includes Tōei Animation—the creators of the anime; Viz Media—the American licensor and publisher of the manga; and FUNimation—the American licensor and dubbing company of the anime. I contacted them by Twitter and followed up by email, asking, “What is Dragon Ball’s genre? Is there an official answer?”

Unfortunately, they never replied.

On to step two: examining their websites.

Unfortunately again, it turns out that they either don’t define Dragon Ball’s genre or it has several genres.

For example, Viz’s website has no genre for the manga. Instead, it describes Dragon Ball Volume 1 with the following text. “Before there was Dragon Ball Z, there was Akira Toriyama’s action epic Dragon Ball. … With a magic staff for a weapon and a flying cloud for a ride, Goku sets out on the adventure of a lifetime…”[1] There we see ‘action,’ ‘epic,’ and ‘adventure,’ with the first two attempting to define the series with adjectives, if not a specific cross-genre of ‘action epic.’

According to Jason Thompson, a former editor of Dragon Ball at Viz from 1996 to 2006, “Dragon Ball is, basically, a martial arts story with elements of fantasy, science fiction, and comedy.”[2] This is true, but Jason doesn’t outright define a genre. That’s why I followed up with Jason by Twitter on February 9, 2016, and he replied, “’Battle manga’ is the katakana term. Beyond that, ‘martial arts-science fiction-fantasy…’”

So that’s ‘martial arts, fantasy, science fiction, comedy, and battle.’ Combined with ‘action epic’ we already have 6 genres.

Tōei Animation’s English website defines the Dragon Ball, Dragon Ball Z, and Dragon Ball GT anime as “action/adventure.”[3] This is accurate, but take note at what’s missing. They don’t mention the fantasy, humor, martial arts, or other aspects.

FUNimation’s site for the Dragon Ball anime says: “action, adventure, comedy, fan service, fantasy, martial arts.”[4] For Dragon Ball Z it says the same thing except it replaces “fan service” with “mystery.”[5] Then for Dragon Ball GT it says the same as for Dragon Ball Z, but adds “shōnen.”[6] It’s odd that “shōnen” would be in GT, but not the original Dragon Ball – the definitive shōnen series.

Combining the official company’s definitions we have: ‘action, action adventure, action epic, adventure, battle, epic, fan service, fantasy, martial arts, mystery, science fiction, and shōnen.’

That’s 12 different genres.

How can a single series be classified as 12 different genres?

That defeats the purpose of having a genre!

Ideally, a genre should classify a piece of art into a single category so it can be made easier to understand. Two, maybe three, at most. But here we have 12 different genres.

If the official companies can’t agree on Dragon Ball’s genre, then we have a problem.

With that in mind, I asked the fans. Maybe they know better than the creators.

Fan-Defined Genre

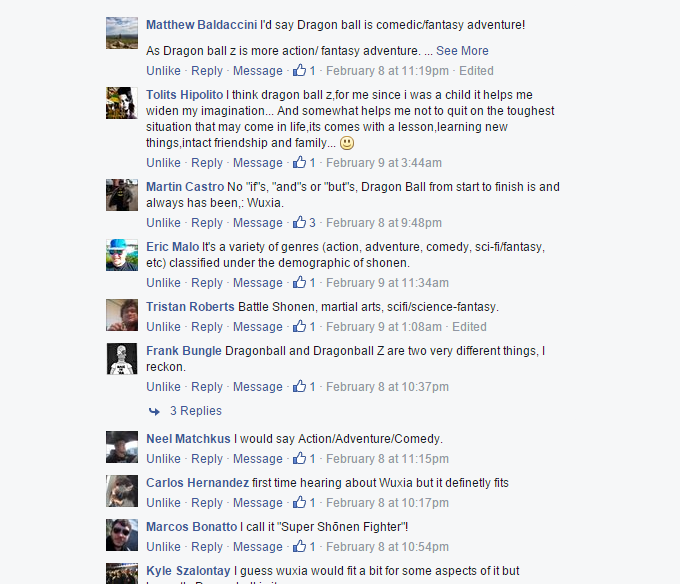

I asked Dragon Ball fans on Facebook, Twitter, and Reddit, “What genre is Dragon Ball?”

They replied: ‘action, action martial arts, adventure, action adventure, action adventure comedy, action comedy, action comedy adventure, action fantasy, battle, comedy, comedic fantasy adventure, family, fantasy, fantasy adventure, martial arts, martial arts adventure, martial arts comedy, martial arts-themed fantasy, parody martial arts, science fantasy, science fiction, shōnen, shōnen battle, super power, super shōnen fighter, and wǔxiá.’ Plus the cross-genres: ‘superhero-fantasy-comedy-science fiction-action, martial arts-science fiction-fantasy, martial arts-science fiction-adventure-comedy-soap opera, martial arts-science fantasy-space epic-adventure-comedy, and martial arts-science fiction-fantasy-adventure-comedy-epic.’

That’s 31 genres. Some are exclusive, some are inclusive, but why is there such variety? The answer to our question should be objective, but instead it’s subjective. In the end, which genre is it? Or is it all of them at once?

Why can’t fans unanimously state, “Dragon Ball is THIS genre!”?

Dividing the Series with Genres

Some fans also said that “Dragon Ball” is one genre while “Dragon Ball Z” is another genre. This is because in the West, the Dragon Ball series is marketed as two different stories, with different buzzwords and emotions. So fans are taught to perceive the one series as two series.

For example, an American fan named Tsali said, “Dragon Ball was about adventure and new surprises. Dragon Ball Z was about pushing yourself and always having the apocalypse around the corner.”

Dividing the series into two is not what Akira Toriyama had in mind. His manga is 42 volumes long and is titled “Dragon Ball” from beginning to end. “Dragon Ball Z” is a title exclusive to the anime that begins at the start of Volume 17 of the manga and concludes at Volume 42.

To be fair, this decision was made by Tōei Animation in Japan, long before it was exported overseas. However, when brought to America, the Dragon Ball Z anime was a bigger success than the Dragon Ball anime, which was initially a failure, so Dragon Ball Z is what caught on. It’s only after Dragon Ball Z was successful that, years later, the original Dragon Ball anime was dubbed in its entirety. The same applies to the manga published by Viz, where they divided it into two different series, with the emphasis being placed on Dragon Ball Z.

As a result, fans were taught to apply different genres to each portion at large. Whether consciously or subconsciously, we all pretty much do it this way because it’s how we’re conditioned.

Maybe this approach seems warranted, but in addition to not being what the author intended, it just doesn’t work when you break it down into specifics.

To find out why, we first have to understand Toriyama’s intention. Then we have to analyze each of these genres in turn and see what’s true and what isn’t.

Toriyama’s Intention

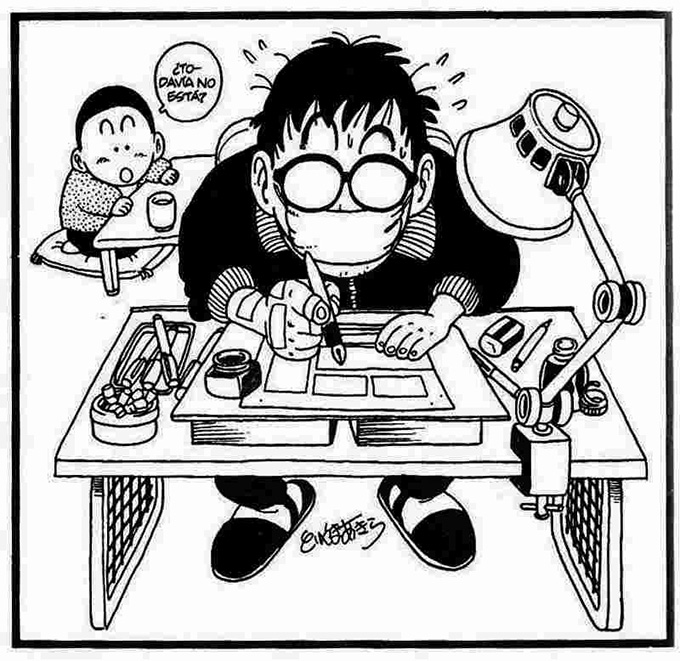

Akira Toriyama creates Dragon Ball because he’s forced to do so. As I describe in Dragon Ball Culture Volume 1, in 1984 he’s been working on Dr. Slump for 5 straight years and is burnt out. He wants to quit Dr. Slump, so his editor, Kazuhiko Torishima, tells him that he can quit if he starts working on a new series right away.

Toriyama doesn’t want to do this, but he doesn’t see an alternative. So they sit down inside Toriyama’s home in Nagoya, and they try to come up with an idea. They struggle for several hours, and then Toriyama’s wife, fellow manga creator Mikami Nachi, tells Torishima-san about her husband’s peculiar habit while he works. It turns out that instead of listening to the radio like other manga authors, Toriyama watches TV. This shouldn’t be possible because illustration and TV are both visual mediums, right? But somehow Toriyama makes it work. She goes on to say that he obsessively watches Jackie Chan’s movies while he works. In particular the film titled Drunken Master (1978).

Torishima-san jumps on this as an opportunity. He figures if Toriyama loves Chinese martial arts movies, then he should make a Chinese martial arts manga. Toriyama refuses, saying, “The things I like and the things that I can draw in manga are different, so I don’t want to.”[7] But Dr. Slump is Shueisha’s biggest cash cow, so he can’t have his star author refuse to create a new series. With no alternative idea, Torishima-san sets up a schedule and forces Toriyama to do it.

Weeks go by and Toriyama hasn’t come up with anything. It’s at this point that he decides to use the Chinese folktale of Xīyóujì (西遊記, pronounced ‘shee-yoh-jee,’ Japanese: Saiyūki, ‘sigh-yoo-key,’ “Journey to the West,” 1592) as the storytelling framework. He says in Daizenshū 2 that this story is, “absurd and has adventurous elements, so I guess I decided to make a slightly modernized Saiyūki. I thought it would be easy if that story served as the basis, since all I would have to do would be to arrange things.”

But, being the contrarian that he is, he decides not to make it a simple arrangement. Instead, he creates an original story with original characters, inverted characters (where males become females and religion become science), and adds more humor.

Dragon Ball is coming fresh off the heels of Dr. Slump, a gag manga to the core. So there’s bound to be a lot of jokes. And since Dragon Ball is based on Xīyóujì, the quintessential East Asian adventure story, it only makes sense that Toriyama’s version begins as an adventure story. In this case, he switches the Buddhist sūtra to the dragon balls, and this fetch quest serves as the story’s motivation. He then mixes Chinese and Japanese culture with Western Hollywood culture and martial arts to create the story’s first arc.

With that in mind we can define the first arc of Dragon Ball as an ‘adventure-comedy-fantasy-martial arts-science fiction’ manga.

Torishima Changes Dragon Ball

Here’s the kicker.

Unfortunately, Toriyama’s version of the story isn’t popular with fans. Dragon Ball only exists in the first place because of Jackie Chan films, but in the first story arc there are hardly any fights, and the ones that are present are over quickly.

The manga is on the verge of being canceled. As a result, after the first story arc is complete, Torishima-san forces Toriyama to change the format. He transforms it from an ‘adventure manga’ into a ‘battle manga.’

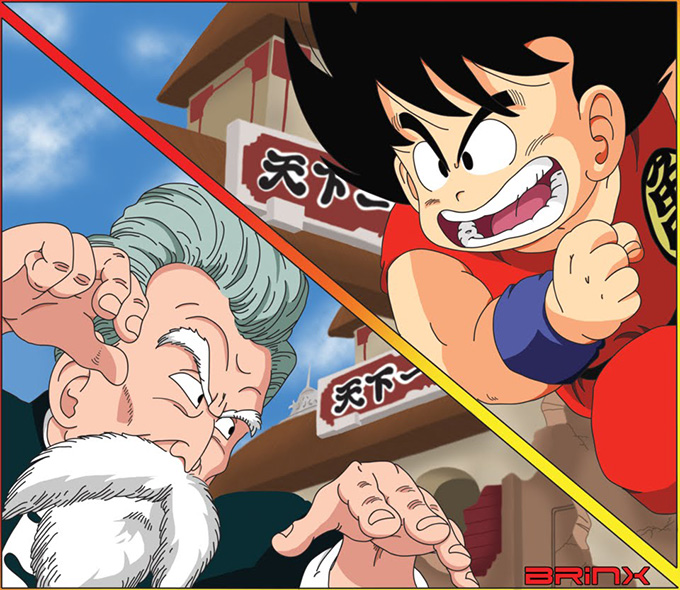

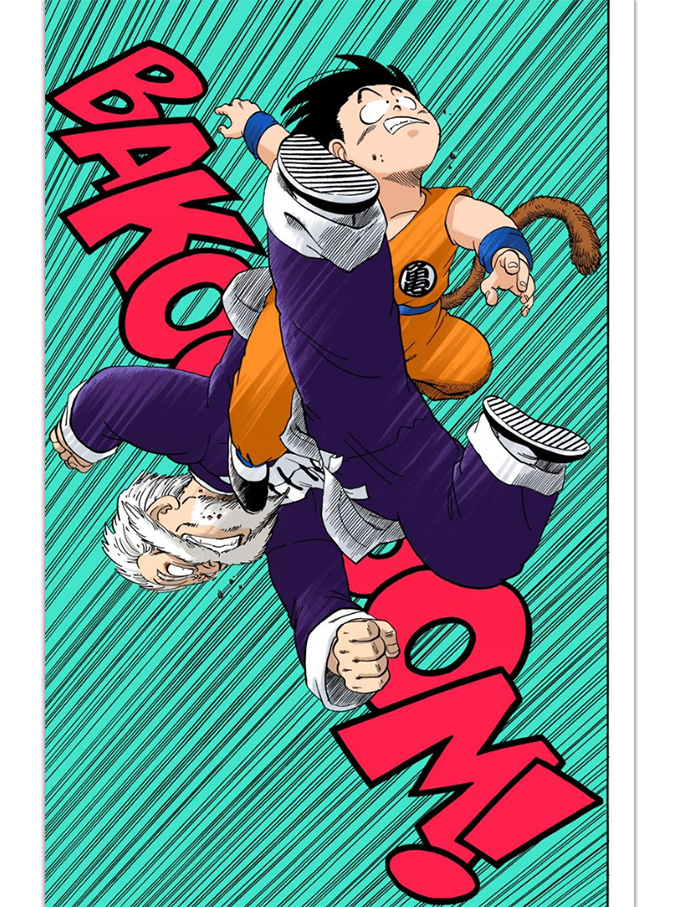

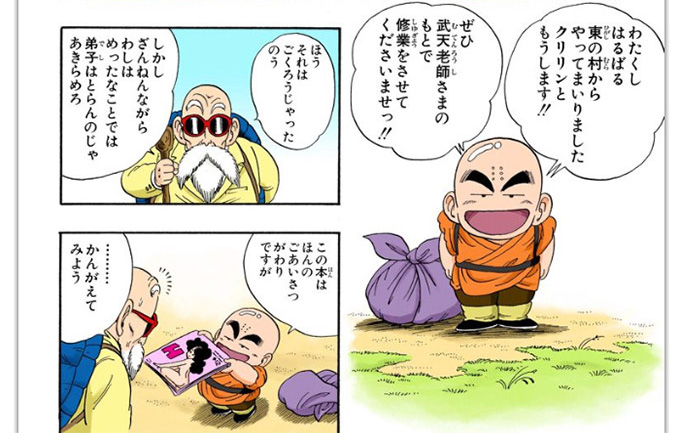

From Chapter 24 onward, Dragon Ball is now focused on Goku’s ever-constant ‘quest for greater strength.’ He becomes a disciple of Muten Rōshi, meets Krillin, and competes in the 21st Tenkaichi Budōkai. As a result, the battles excite the fans, and the series becomes the biggest financial success of the 1980s and early ‘90s manga and anime scene.

With that in mind we can call the second arc of Dragon Ball a ‘martial arts-battle-comedy’ manga. There’s no adventuring to be had. They just train and fight.

So the first arc is ‘adventure’ and the second arc is ‘battle,’ and it would be great if we could end this conversation here, but it’s anything but that simple.

That’s because after the second arc is complete, Goku goes on another adventure. It just so happens that this adventure is full of battles—against the Red Ribbon Army.

After that, he enters the 22nd Tenkaichi Budōkai for another round of battles. Then, his best friend dies and it becomes a revenge story that propels Goku into another adventure which, you guessed it, leads to more battles. And it’s here where the story becomes even more action-oriented and shifts toward how fans perceive the “Dragon Ball Z” content.

This cycle repeats itself throughout the series, where Gokū has battles, goes on adventures, and has more battles.

So which is it? One of these two genres, or maybe both?

Transforming Manga

Like the characters within its pages, Dragon Ball transforms itself over its 10 years of publication. The adventure-to-battle format eventually evolves into a ‘science fiction Bangsian fantasy’—which I’ll explain in a moment—and after that, it bounces between genres at will, finally coming back to the sillier humor that it started with.

What’s the reason for these changes?

Toriyama loves movies and they have a great influence on his work. Like a manga-fied version of a film director, Toriyama uses Dragon Ball as a playground where he can direct his own movies and do whatever he wants. He makes it up week to week, and as he’s coming up with ideas and drawing his illustrations he gets influenced by the movies he’s watching on TV. This chaos is then guided by his editors who either “reject” his ideas or alter them to suit the interests of the audience.

As a result, Toriyama changes the genre from story arc to story arc.

That makes it hard to define Dragon Ball as a single genre. It also makes it possible for fans to subjectively define the series as whatever genre they connect with the most. If they connect with the humor, then they’ll be sure to say it’s a comedy, and if they connect with the action, they’ll be sure to say it’s an action series.

Let’s take a deeper look at these genres and see why fans still can’t make up their mind.

Adventure

Dragon Ball begins as an adventure story. It’s right there in the introduction to every episode, with a theme song titled Makafushigi Adobenchā! (魔訶不思議アドベンチャー!, “Mystical Adventure!”).

The series is inspired by the Chinese adventure story of Xīyóujì, which becomes the Japanese Saiyūki. The Tang Monk’s adventure from China to India and back again was thousands of years in the making, and Toriyama uses it as the basis for Goku and Bulma’s adventure to collect the dragon balls. So the first arc of Dragon Ball, which I call the Saiyūki Arc, is an adventure story.

This includes Chapters 1 to 23, out of a total of 519 chapters, and represents 5% of the story.

Afterward, it experiences its first transformation.

Battle

Dragon Ball becomes a batoru manga (バトル漫画, “battle comic”) at Chapter 24, which is the start of what I call the Shugyō Arc (修業, “Austere Training Arc”). Goku trains with Muten Rōshi to become a supernormal martial artist. Then he enters the 21st Tenkaichi Budōkai and begins his battles.

The batoru genre is dedicated to the advancement of the main character’s strength through battle. Batoru manga has three principles: yume (夢, “dreams”), yūjō (友情, “friendship”), and batoru (バトル, “battle”).

In batoru manga the main characters have a big dream, so they challenge themselves to be the best. The road to success is difficult, but along the way they’ll make friends and rely on them to overcome hardships. Their hardships arrive in the form of battles with opponents who have different motives than their own, and who represent external goals to overcome as they climb the ladder toward higher levels of internal realization.

A batoru manga places emphasis on the idea of the main character and his friends getting stronger. As they gain strength, their minds and bodies transform, which allows them to take on the challenge of the next highest level. This continues until their dream is achieved.

In the case of Goku, the story never ends because his dream never ends. There is no limit to “becoming stronger,” so Goku continues to train.

Dragon Ball is the world’s #1 batoru manga, so it’s safe say that this genre should always apply to any story arc after the first. Even if it’s an adventure arc, those adventures are only occurring because Goku is heading toward his next battle as he chases his dream. The amount or severity of fights isn’t important; what’s important is that they’re dedicated to the advancement of Goku’s strength. He is fighting an internal battle as he fights his external battles, and that applies to the entire series from the moment he becomes Muten Rōshi’s disciple.

That means Chapters 24 to 519, which is 95% of the series, are a “battle manga.”

Martial Arts

When Dragon Ball becomes a batoru manga it also becomes a “martial arts manga” because that’s the form through which the characters fight their battles.

“Martial arts” is considered a subgenre of “action.” In Japanese this would be called the budō-no-manga (武道の漫画, “martial arts comic”) genre.

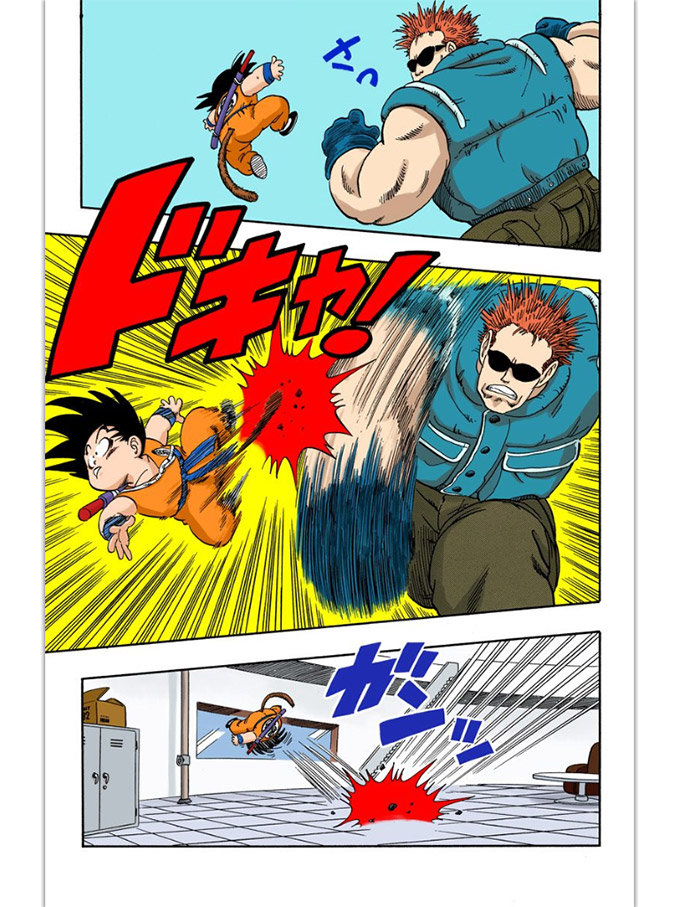

Dragon Ball is inspired by Jackie Chan and Bruce Lee’s martial arts films. In Chan’s case his action is mixed with humor, while in Lee’s case they’re serious and realistic. Dragon Ball has both styles of martial arts combat and Toriyama bounces between them depending on the mood of the battle.

Even the first story arc still has occasional martial arts action. The only reason it wasn’t overflowing with martial arts is because Toriyama is a self-declared “contrarian” and purposefully reduced that action in order to not give fans what they wanted to see. Sounds silly, but that’s how his mind works. It’s only because of Torishima-san’s influence that the series becomes more martial arts-focused after this first arc finishes.

For that reason, 95% of Dragon Ball is a “martial arts manga,” even if Toriyama didn’t want it to be at first.

Kakutō Manga

Speaking of battles and martial arts, I have to add this to the list, because according to the Japanese Wikipedia, Dragon Ball is defined as a kakutō manga (格闘漫画, pronounced ‘kah-ku-toh,’ “fighting comic”). Not battle, but ‘fighting.’

Kakutō manga refer to manga in which a single martial art is the vehicle through which the story is expressed, such as through boxing, karate, kendō, or jūdō.

For example, Ashita no Jō (あしたのジョー, “Ashita no Joe,” literally, “Tomorrow’s Joe,” 1968) is a seminal boxing manga that became an icon of Japan’s 1970s generation. Another is Karate Baka Ichidai (空手バカ一代, “Karate Master,” literally “A Karate-Crazy Life,” 1971), which is inspired by real-life karate master Ōyama Masutatsu (大山 倍達, “Mas Oyama,” July 27, 1923 – April 26, 1994).

Both stories focus on a single sport, as do most others defined as kakutō manga. If we go by that definition, then I’d argue against Dragon Ball being defined as a kakutō manga, because it’s not focused on a single martial art.

However, kakutō manga can also be translated simply as “martial arts comic,” which broadens the definition. This then includes hundreds of manga where fighting is the norm, regardless of the type of fighting it is – whether unarmed or armed. So long as martial arts are the vehicle through which character development is expressed, then it’s a “martial arts comic.” With this loose definition, Dragon Ball is a kakutō manga.

Even though Dragon Ball can be a kakutō manga if you purposefully define it that way, I prefer the stricter definition where it’s focused on a single martial art; otherwise the definition loses meaning. I feel that if you’re going to call it a kakutō manga with a loose definition, then you might as well just call it a “martial arts manga.”

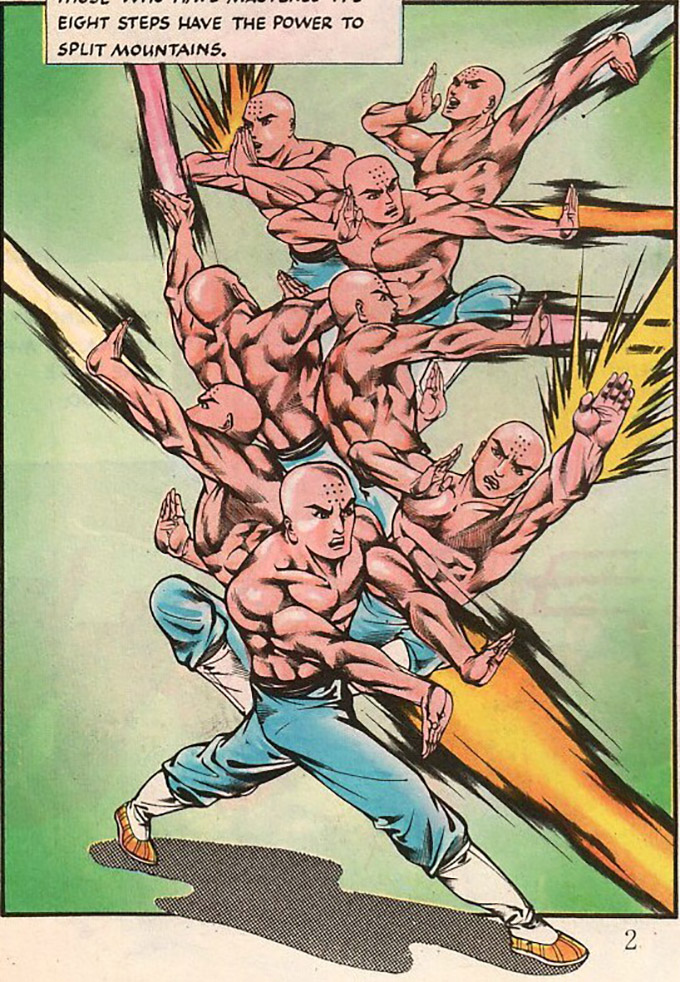

Wǔxiá

Coinciding with the above switch to a batoru manga, Toriyama and Torishima-san (arguably) begin to add in elements of wǔxiá.

Wǔxiá (武侠, pronounced ‘woo-shya,’ “martial hero”) is a genre of Chinese martial arts novels, films, and comics popular in East Asia and Southeast Asia. Wǔxiá stories are set in a fantasy world that is similar to China – but not actually China – called jiānghú (江湖, “rivers and lakes”). It’s made of lush plains, grandiose mountains, mystical temples, lavish Chinese cities and villages, and inhabited by monsters.

Within this fantasy realm is a secret community of martial artists collectively called wǔlín (武林, literally “martial forest,” but meaning “martial world”). The young hero of the story is often an idealistic martial artist who trains under a master or within a secret society, and during his adventures he encounters supernormal Buddhist monks, Dàoist magicians, immortal sages, villains, and other wandering disciples. The hero has to train hard, look within, and continually reach the next level in order to attain his dream.

These stories often involve major themes in Chinese culture, such as endurance, truth, or compassion, where the character is an idealist who suffers great pain and faces near-death adversity, yet offers mercy to his enemies, making allies and friends along the way.

The biggest similarity is the reliance on supernormal martial arts techniques which are dependent on qì (ki). These include supernormal speed, power, toughness, projection of external energy as a weapon, self-powered flight, energy healing, supernormal vision, cross-dimensional travel, and so on.

At the moment it’s unclear where Toriyama receives his inspiration for adding wǔxiá-like elements into Dragon Ball. Toriyama loves movies, so the immediate reaction is to look to the movies. But in an attempt to find cinematic predecessors, I’ve watched hundreds of kung fu and wǔxiá films released prior to the creation of Dragon Ball in 1984, and unfortunately I haven’t found much evidence to support this argument.

The next is to look to Hong Kong comics that feature similar martial arts fighting and character archetypes. The combat does look similar to Dragon Ball, but the chances are high that Toriyama never read these comics. He has said multiple times that he didn’t have time back when he was creating Dragon Ball to read manga from his own peers, let alone Chinese language comics which were likely never exported to Japan prior to 1984.

You can read more about the evidence (or lack of evidence) that connects the two in my upcoming “Dragon Ball and Wǔxiá” article.

Even though there is nothing beyond circumstantial evidence to link Toriyama’s development process to the wǔxiá genre, in the final product there are a lot of similarities. Perhaps too many to be coincidental. So if we’re going to say that Dragon Ball is of the wǔxiá genre, then just like with “battle” and “martial arts,” it begins at Chapter 24 and consists of 95% of the series.

Action

“The #1 action anime of all time!!” Oh yeah, here we go!

Wikipedia describes the action genre as, “A genre in which one or more heroes are thrust into a series of challenges that typically include physical feats, extended fight scenes, violence, and frantic chases.”[8]

That’s Dragon Ball alright!

But with that said, I’d argue that the first story arc does not count as “action.” Same for the Shugyō Arc, because that’s just training. Likewise the 21st Tenkaichi Budōkai Arc, because even though it has a lot of fighting, that’s a definitive “battle” genre period.

The fact is, Dragon Ball becomes an action series at the start of the Red Ribbon Army Arc when Goku is traveling on his own and facing one threat after another. That whole arc is like a giant action film. In particular, the James Bond series mixed with Bruce Lee’s Game of Death (1978), plus a few others, like Indiana Jones (1981) and Alien (1979).

The Red Ribbon Army Arc starts at Chapter 55. That means the first 54 chapters of Dragon Ball are not an “action manga.” And since they account for 10% of the series, it isn’t accurate to define Dragon Ball as an “action manga” from beginning to end.

That said, the other 90% is action, so it is logical to call Dragon Ball an “action manga” overall.

Toriyama incorporates action into his story by setting Goku on another adventure, thus turning Dragon Ball into an “action adventure” story. Goku travels across the world in search of his 4-Star dragon ball, and as a result of that search he fights battles, meets his friends, trains, and has more fights, with movie-like set pieces tying each segment together.

Following this arc he enters The 22nd Tenkaichi Budōkai, which is another “battle” period. The conclusion of this leads to a revenge story straight out of Hong Kong martial arts films, which is more “action adventure,” and includes further training and a huge battle. Then we enter the 23rd Tenkaichi Budōkai for another “battle” phase, and it continues into more “adventures.”

Goku’s action-oriented adventures, followed by battles, continue like this for the life of the series. He’s either adventuring, fighting, or training for a fight – sometimes by adventuring. For that reason it can be tough to divide the series up into ‘adventure’ or ‘not adventure,’ because Goku’s adventures lead him to new battles; which can last for a long time.

Simultaneous Genres

That’s almost it in terms of linear progression and transformation of genres, but there’s a lot more to Dragon Ball than action, adventures, and battles. These next genres all occur simultaneously across the series, and Toriyama uses them at will.

I present them in order of their relevance.

Comedy

Dragon Ball is one of the funniest manga ever made. There are jokes on almost every page, and you’ll laugh from beginning to end. This is because Akira Toriyama is, in his heart, a gag manga artist. He writes gag manga because this is what he’s inspired to create as a young man. Dragon Ball was a process of an artist and writer being forced to learn how to draw exciting adventures and battles, when really, he’d prefer to write short stories full of perverted humor and whacky scenarios.

This is why the first arc of Dragon Ball is so funny, and again, why the last arc, the Majin Buu Arc, is so silly. He started off that way, and then in the end he decided to return there.

Toriyama is always eager to add more humor into his work. That’s why even in the most serious arcs, such as the Freeza Arc, you have humorous moments. For example, the Ginyu Force are super powerful martial artists who almost kill the heroes, yet are a parody of color-coded tokusatsu characters like the Power Rangers. And Majin Buu is a terrifying and unstoppable killing machine, yet a pink blob monster with a cute face who likes to eat candy.

I argue that 100% of Dragon Ball is a comedy because that’s who Akira Toriyama is as a creator. He wants Dragon Ball to be funny from beginning to end, and he succeeds at it. There are times where it’s funnier than others, but it’s always funny.

The reason I say this genre is the most relevant to Dragon Ball is because everything that’s included in the story is only there because Toriyama wants to tell more jokes. The fantasy, the science fiction, the fighting, and everything else, is a way for Toriyama to tell his story. He uses culture as the vehicle for his jokes.

Fantasy

Wikipedia defines fantasy as, “A genre of fiction that uses magic or other supernatural elements as a main plot element, theme, or setting. Many works within the genre take place in imaginary worlds where magic and magical creatures are common.”[9]

Dragon Ball is inspired by Xīyóujì, which is a fantasy folktale based on the real-life adventure of Xuánzàng, a Tang Dynasty monk. He travels to China and returns with Buddhist scriptures, becoming famous throughout China. Then as time passes, legends grow around his adventures, and they become increasingly outlandish and mystical. Xīyóujì is filled with fantasy elements, from a talking Monkey King, Pig man, and Sand Demon, to dragons, immortals, all-powerful Buddha’s, physical transformations, demons, gods, heaven, hell, and Dàoist magic aplenty. It’s a fantasy in the truest sense of the word.

Dragon Ball uses Xīyóujì as the framework for its first arc, so there are a lot of parallels. We have talking pig men, dragons that can grant wishes, immortal Dàoist sennin’s, high-flying martial arts, supernormal uses of ki energy, magical powers, demons, gods, an afterlife of heaven and hell, and several iconic elements, such as Goku’s magic cloud and staff.

Xīyóujì is set in China, but it’s such a fantastic story that readers often feel that it takes place within its own world. Dragon Ball likewise appears to take place in a “Chinese” setting, but within its own imaginary world, with its own history, official timeline, and geography.

So right from the beginning Dragon Ball is a fantasy. Some might argue that it becomes ‘less fantastic’ as the story progresses, in favor of science fiction, but I’d argue that this isn’t the case. When a man dies, goes, to the afterlife, and trains under a deity, that’s more fantastic than otherwise. Yes, there’s more science fiction as well, but the fantasy doesn’t disappear. Giant dinosaurs are still walking around and wearing hats!

For that reason, 100% of Dragon Ball should be defined as “fantasy.” Fantasy provides the setting for the Dragon Ball world, and in turn, the story.

Bangsian Fantasy

This one isn’t in the ‘official genres’ list or the ‘fans genre’ list, but I’m adding it to the list because of what I just mentioned: Goku’s death and trip through the afterlife.

A Bangsian Fantasy is a genre of literature or film that focuses on a character entering the afterlife and then returning to normal life. Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy is a good example of this genre. It’s an epic poem that tells the story of a poet who is able to keep his mortal body as he enters Hell, adventures through Purgatory, then goes to Heaven, and finally back to Earth.

This is what happens to Goku after he dies in the Saiyan Arc. He is able to keep his body and enters the ano-yo (あの世, “other world”). There he is judged by Enma-Daio, the King of the Underworld in East Asian culture. Afterward he runs across Snake Way, falls into Hell (in the anime), and trains with a deity in higher level martial arts. Afterward, through the power of the dragon balls, he is brought back to life and returns to Earth where he fights in a big battle.

From that point onward the “other world” and the characters within it play a major role in the story.

Therefore, the series is a Bangsian Fantasy from Chapter 204 to Chapter 519. That’s 60% of the series.

Science Fiction

Some fans argue that Dragon Ball becomes a science fiction series at the beginning of “Dragon Ball Z,” which is Chapter 195. But the truth is, Dragon Ball is a science fiction series right from the start.

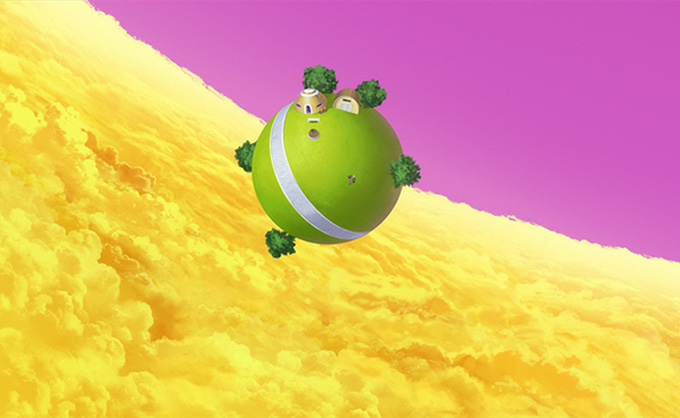

In Dragon Ball Chapter 1 we are introduced to Bulma, a genius scientist who carries a scientific device in her hand called the Dragon Radar, which she invented herself. When Toriyama created this device in 1984 it was way ahead of its time. A palm-sized radar device with geosynchronous location tracking and terrain mapping, with a glossy and simple design, was unheard of in this era. It would take another two decades for the first smart phone with geosynchronous mapping capabilities to be introduced. The Dragon Radar was science fiction at its best; meaning that it was a projection of technology the creator wished existed at the time, but would only be invented years later.

Following that we see the kapuseru (“capsules”). These tiny pill-sized objects can contain any material object, shrinking their particles down while retaining their form, but not their weight, and then at the push of a button returning them to their original state. Bulma uses her first kapuseru to summon a motorcycle out of thin air. This motorcycle has a futuristic design that is likely inspired by the design of the light cycles in Tron (1982). Then in Chapter 2 she uses the kapuseru to summon an entire house.

Shortly afterward, we see levitating air cars inspired by Star Wars (1977), the seminal science fiction film series that Toriyama adores. Then we get to see androids like Major Metallic, cybernetic enhanced men like Cyborg Tao Paipai, space aliens, intergalactic travel, artificial humans, and in Dragon Ball Super, multiple dimensions.

Sometimes the series is more science fiction-focused and other times less, but science fiction is there in the very first pages. It is a “science fiction manga” from beginning to end. 100%.

Science Fantasy

What makes the science fiction elements so interesting is that they coexist with the fantasy, traditional martial arts, and various elements that are otherwise considered the opposite of science fiction. Toriyama places hermit huts, Chinese kung fu, and supernormal ki blasts, demons, and gods, alongside space travel, aliens, cyborgs, androids, mechanical jets, robots, and futuristic training devices like the gravity chamber.

Rod Serling, Hollywood writer and creator of The Twilight Zone (1959), made the distinction between the genres through the voice of the narrator of a 1962 episode titled The Fugitive, saying, “It’s been said that science fiction and fantasy are two different things: science fiction, the improbable made possible; fantasy, the impossible made probable.”

What he then alludes to is that the coexisting of science fiction and fantasy creates a new genre called “science fantasy.” In this genre, the scientific elements give the fantasy elements a realistic coating that makes them seem possible within the setting of the story; often to the point of making rational sense within our own world. It goes so far as to fuse the elements together, whereby they rely upon one another for their coexistence.

Dragon Ball is 100% science fiction and 100% fantasy, thus, 100% of Dragon Ball is of the “science fantasy” genre.

In fact, Dragon Ball is a perfect example of the science fantasy genre and should be recognized as such. When you can’t tell where the ‘fantasy’ ends and the ‘science fiction’ begins, you know the author has done a good job. It all blends together into one seamless experience and you never stop to question it.

Epic

Dragon Ball is a long series, and it covers Goku’s life from his birth to his multiple deaths. For that reason fans sometimes define Dragon Ball as en epic.

An “epic” is by definition a genre of classical poetry. However, in modern times, “epic” is also used in theatre, literature, and films. For example, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings is considered a quintessential example of the “epic fantasy” subgenre.

Wikipedia says, “Epic fantasy has been described as containing three elements: it must be a trilogy or longer, its time-span must encompass years or more, and it must contain a large back-story or universe setting in which the story takes place.” With that in mind, I’d say that Xīyóujì is an epic, and in turn, Dragon Ball.

I think the ‘trilogy’ aspect is meaningless, because that’s just an arbitrary division made by an editor. In Tolkien’s case, he hated the idea of splitting the story into 3 books. Likewise, in Dragon Ball’s case, it wasn’t Toriyama’s idea to divide his manga into the “Dragon Ball” and “Dragon Ball Z” portions. That’s just marketing driven. What matters is the length and scope of the story.

Of course, Toriyama didn’t intend for it to become an epic. He was barely able to complete a new chapter each week, and he thought about ending the story multiple times. It’s a wonder that it lasted as long as it did.

And consider this: the individual arcs within the series do not qualify as self-inclusive epics. It’s the points ‘between’ the arcs where Toriyama skips ahead by 3 to 5 year increments that advance the plot forward so many years. In fact, most of the arcs occur within the span of a single day, a few days, or weeks. It’s those long ‘time-skips’ that allow Dragon Ball to advance forward in years so quickly. And it’s this long expanse of time that makes fans feel the series – as a whole – is an “epic.”

This is to say, Toriyama created his epic by accident.

The question is, ‘what type of epic?’ Is it a “fantasy epic,” a “science fiction epic,” or a “martial arts epic”?

If we’re going to call Dragon Ball an epic, then you have to say that 100% of the story contributes to this definition. Therefore you have to tack “epic” on to any genre definition you come up with for the series as a whole. For example, ‘action-adventure-comedy-science fiction-fantasy-epic.’

Family

A fan in the Philippines named Dexter said Dragon Ball is part of the “family” genre. This response took me by surprise and I immediately wanted to dismiss it, but let’s take a closer look.

“Family” is a popular genre of literature and film. It may not be a main genre, but its right up there with documentaries. Hundreds of family-focused works are produced every year across the world, often intended to promote family values.

Dragon Ball is marketed as a family friendly show in Japan. It is aimed at young boys from age 8 to 16, and it’s filled with positive values of perseverance, endurance, and optimism. This is true despite the martial arts action and occasional violence. In fact, the martial arts are the vehicle through which the family values are passed on, so you can’t throw the baby out with the bath water if you don’t like the violent aspects. Like genuine martial arts paths of self-cultivation, Dragon Ball teaches self-improvement, fortitude, self-understanding, and in turn, understanding of others.

When I followed up with Dexter to ask why he chose this genre, he said, “From what I can see, in DBZ they care for each other even though they don’t all come from the same planet and race.”

I understand this to mean that a theme in the series is having tolerance. That does seem to play a role. In fact, ‘mercy and redemption’ is one of the central themes, whereby Goku makes it possible for the villains he fights against to find gradual redemption and even salvation. They start off as his opponent and then become his ally and friend. We see this with just about everybody, including Bulma, Oolong, Yamcha, Krillin, Tenshinhan, Piccolo, and Vegeta.

In addition, “family” is presented to us in marketing images, along with anime intro and outros, where we see Goku holding arms with his extended family, giving big smiles.

The question is, ‘Is this “family” content there because it’s conforming to this genre’s characteristics on purpose, or just a causal result of Toriyama telling his story?’ Maybe the morals and ethics are happenstance, like so much of the deeper meaning in the series.

I don’t have an answer, but it can’t be denied that this content is found from beginning to end. With this in mind, it’s fair to say that 100% of Dragon Ball is the “family” genre, whether intentional or otherwise.

I don’t think it’s the main genre, but that’s my opinion, and it all depends on how you want to market the series or present it to others. It’s marketed as a family-related show in Japan, but it certainly isn’t marketed that way in America. I’ve been indoctrinated by the American marketing machine, so it’s possible I’m looking at it from a different perspective. Maybe Dragon Ball really is supposed to be a family show.

Shōnen

A lot of fans say, ‘Dragon Ball is a shōnen manga.’ This is correct, however, shōnen (少年, “young boys”) is not a genre, it’s a target demographic of boys aged 8 to 16. Within the shōnen demographic there can be multiple genres of stories, from sports, to mysteries, high school dramas, adventure epics, and battles. That’s why Weekly Shōnen Jump, the manga anthology Dragon Ball is published in, can have so many different types of stories within each issue.

The reason ‘shōnen’ is one of the most common answers among fans is because shōnen is a widely spoken term in the industry and a buzzword used in marketing. You see it associated with Dragon Ball all the time, so it seems natural to equate the two. When you see something like ‘#1 shōnen manga’ you’re bound to presume that shōnen must be its genre.

Shōnen is an overarching umbrella under which Dragon Ball falls into being classified, but it is not a genre unto itself. For that reason, 0% of Dragon Ball can be classified as belonging to the shōnen genre, because there is no such genre.

That said, Dragon Ball is the #1 shōnen manga and anime of all time.

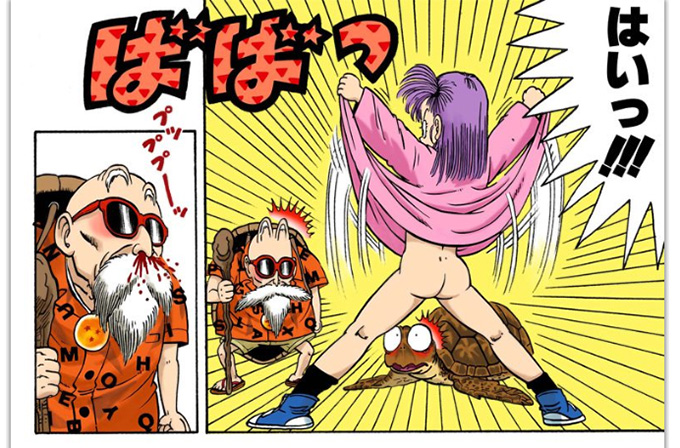

Fan Service

FUNimation listed the original Dragon Ball anime as being in the “fan service” genre. Fan sābisu (ファンサービス “fan service”) is an anime and manga specific term used to describe content in a series that exists solely for the sake of pleasing its fans. It’s most often used to add gratuitous sexuality, violence, explosions, or self-referential humor that pokes fun at the medium itself, in an attempt to give fans what they want. For example, a young girl bends over and shows off her panties, exciting the young male audience.

The only possible reason I can conceive of for defining Dragon Ball as “fan service” is the brief amounts of nudity and perverted humor in the first story arc, plus the continual escapades of Kame-sennin. Perhaps it’s there as a warning to potential buyers that yes, you will see boobies.

The term wasn’t used prevalently in the manga and anime industry when Dragon Ball was being made, so it’s only in hindsight that you can look back and apply it anyway. And I don’t think it applies. Any instance of supposed ‘fan service’ is just Toriyama doing what he does best.

For that reason, I say that 0% of Dragon Ball is “fan service.”

Mystery

FUNimation lists the Dragon Ball Z anime as being of the “mystery” genre, but I have a difficult time figuring out why. Dragon Ball is a suspenseful series because of the way Toriyama writes each chapter. There are a lot of sudden twists and revelations, such as the surprise origin story for the main character. In addition, he always leaves you on a cliffhanger and you never know what’s going to happen next. This, in turn, gives Goku his motivation for the next arc and propels the cast forward.

But does that qualify as a “mystery?” It’s not like in a mystery novel where a particular event happens, and then the hero spends the rest of the story trying to put the clues together and solve the mystery.

The only arc that comes close is the Cell Arc, which is contained within the greater Artificial Humans Arc (i.e. “Androids Arc”). You’re not sure who the main villain is, and it escalates until we reach Cell. Maybe that’s what FUNimation had in mind. But I think that’s just more of Toriyama’s writing style at work, where you’re left questioning what will happen next.

For that reason, I will say that 0% of Dragon Ball can be defined as “mystery.” Same for “horror” while we’re at it. I don’t care if some parts seem scary – like Cell drinking people with his tail; Dragon Ball is not a horror series.

Genre Percentages

That’s all of the genres!

Here is a recap of my classifications for the percentage of each genre within Dragon Ball.

Adventure: 5%

Battle, Martial Arts, Kakutō, Wǔxiá: 95%

Action Adventure: 95%

Action: 90%

Comedy: 100%

Fantasy: 100%

Bangsian Fantasy: 60%

Science Fiction: 100%

Epic: 100% – by happenstance

Family: 100% – by happenstance

Shōnen: 0% – by disqualification, but 100% in principal

Fan Service: 0%

Mystery, Horror: 0%

The Best Series Ever: 9001%

Arc by Arc Genre Classification

Here are my own genre classifications for each arc of the series.

Saiyūki Arc: adventure-comedy-science fantasy-martial arts

Shugyō Arc: martial arts-comedy-battle

21st Tenkaichi Budōkai Arc: battle-comedy-martial arts-science fantasy

Red Ribbon Army Arc: action adventure-martial arts-science fantasy

22nd Tenkaichi Budōkai Arc: battle-comedy-martial arts

Piccolo Daimao Arc: action adventure-martial arts-science fantasy-battle

23rd Tenkaichi Budōkai Arc: battle-comedy-martial arts

Saiyan Arc: action adventure-martial arts-science fantasy-bangsian fantasy-battle

Freeza Arc: action adventure-martial arts-science fantasy-bangsian fantasy-battle

Artificial Human Arc: action adventure-martial arts-science fantasy-bangsian fantasy-battle

Majin Buu Arc: action adventure-martial arts-science fantasy-bangsian fantasy-battle

Defining Dragon Ball’s Genre

If Dragon Ball has 100% of this, 90% of that, and another 95% of this and that, how can it be all those things at once, and yet none of them at the same time?

It’s tempting to say that ‘Dragon Ball’s genre is “Dragon Ball.” It is a genre unto itself!’

However, that’s a circular argument. It also doesn’t help us when new series are made that are inspired by Dragon Ball and share similar cross-genre traits, such as Naruto (1997).

To solve the fundamental problem, I have to create a new genre and coin a new term.

Fusion Manga

I define Dragon Ball’s genre as “fusion manga,” and in turn, “fusion anime.”

The purpose of genres is to classify a work of art into an easy-to-understand box. That’s why you’re only supposed to use one or two genres. A fusion manga is a series that defies the boundaries of one, two, three, or even twelve genres.

Toriyama creates Dragon Ball by fusing multiple genres together right out of the gate. Then after that, his story and his characters experience a transformation and he adds more genres into the work. This is why it’s impossible to define Dragon Ball as a single genre. This is why the official companies can’t agree on its genre or don’t try to define it. And this is why fans have over 30 different ways to describe it.

Here is Dragon Ball’s actual genre:

“Action adventure-martial arts-battle-wǔxiá-comedy-science fantasy-bangsian fantasy-family-epic.”

That’s a mouthful. Instead, you can say it’s a “fusion” genre. Then if you need to add more, say it has the subgenre written above.

This works for other series too. For example, Naruto would also be a “fusion,” but with its own unique subgenre elements.

Fusion is a common trend nowadays in the restaurant industry, where it’s called ‘fusion cuisine.’ For example, in New York City there is a restaurant that combines Israeli and Spanish food together. Others have Mexican and Chinese, or Italian and Japanese. With this model you can combine any two cultures of cuisine together. But the key here is that it’s two cultures. If you do more than that, you end up with a dish that is neither fish nor fowl.

Toriyama’s accomplishment is that he mixes these different genres together inside a pot, bakes it for 10 years, and has it come out tasting delicious.

Dragon Ball is Fusion

In Dragon Ball’s 30-year history no one has ever attempted to do what I just did.

I believe my conclusion is the most logical argument. Otherwise you will leave something out and your definition will be incomplete.

Dragon Ball’s genre should henceforth be defined as “fusion.”

Footnotes

[1] Vizmanga.com – Dragon Ball

[2] Jason Thompson’s Article on Dragon Ball

[3] Toei-Animation.com – Dragon Ball

[4] FUNimation.com – Dragon Ball

[5] FUNimation.com – Dragon Ball Z

[6] FUNimation.com – Dragon Ball GT

' . $comment->comment_content . '

'; } } else { echo 'No comments found.'; }