Cultural Origin of Zen-ō’s Button

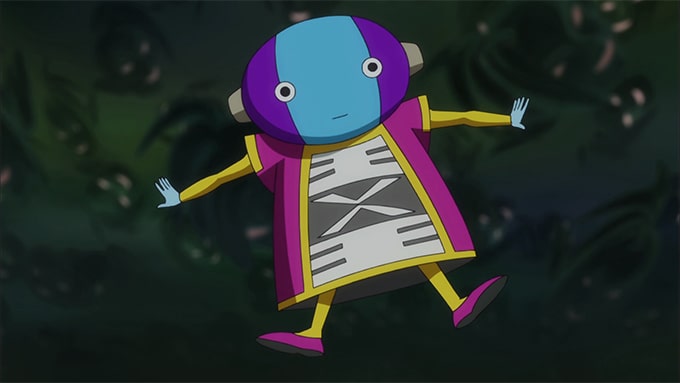

Zen-ō’s button allows anyone to summon the lord of all gods to their side. But where did Toriyama receive the inspiration to create this device? Read this article to learn the cultural origin of Zen-ō’s button in Dragon Ball Super!

Zen-ō’s button first appears in Episode 55 of Dragon Ball Super, titled “Hey, I Wanna Meet Son Goku — A Summons from the Omni-King!”

In Episode 55, Zen-ō summons Goku to ask Goku to become his friend. Goku then invites him to Earth for a visit. In response, Zen-ō gives Goku a call button that he can use to summon Zen-ō to Goku’s location anytime he wants.

He says, “If you press this button, I’ll come immediately.”

Goku then presses it while it’s in Zen-ō’s hand, and of course it does nothing because Zen-ō is already standing there.

The call button looks like a small round disc that fits in the palm of Zen-ō’s childlike hand. There’s a large button in the center of it. On the reverse side is another button, which will bring Goku to wherever Zen-ō is located.

This button doesn’t have a special name. In the original Japanese, Zen-ō just calls it a botan (ボタン, “button”), which is the foreign loanword for such a device.

However, I know Dragon Ball fans like to give everything in the series a special name even if there isn’t one. So I suppose if you had to give it a name, then you could call it Zen-ō-sama no botan (全王様のボタン, “Omni-King’s Button”).

So where did the creator of Dragon Ball Super, Akira Toriyama, get this idea?

According to my research, Toriyama was inspired by a similar device in a Japanese superhero series about an all-powerful robot from outer space who loves to protect children.

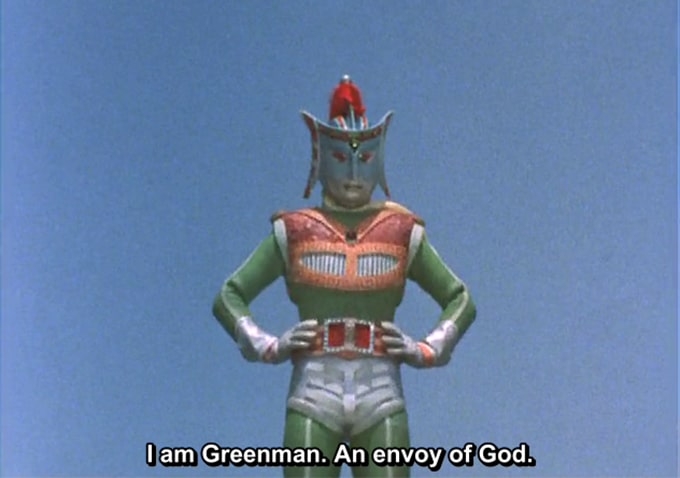

Calling Greenman

Tokusatsu (特撮, “special effects filming”) are a genre of television show starring a hero who fights a unique monster of the week.

The most famous tokusatsu show is Urutoraman (ウルトラマン, Ultraman, 1966). However, there are others aside from Urutoraman, including many low-budget and lesser-known series.

It’s in one of these low-budget series that we find the original inspiration for the call button used by Zen-ō in Dragon Ball Super.

I discovered this in the show called Ike! Gurīnman (行け! グリーンマン, “Go! Greenman”).

Ike! Gurīnman is an early tokusatsu TV show produced by Toho that ran from November 12, 1973 to September 27, 1974.

Toho is the producer of Godzilla and other kaijū (怪獣, “strange creature”) films. Many of the monster costumes from these movies were reused or re-purposed for these shows, such as the Japanese King Kong equivalent, and Godzilla’s son, Minilla.

In each of Gurīnman’s 52 episodes, the hero, who is a giant green man sent by Kami (神, “God”), would fight a monster of the week in order to “protect the children.” The main villain of the series was named Ma-ō (魔王, “Demon King,” or “Satan”).

If you’re familiar with Dragon Ball, you’re already seeing a similarity here, as Dragon Ball has both a Kami and a Ma-ō of its own. There are other similarities as well, which I’ll talk about in other posts.

The thin plot is that the Ma-ō was sentenced by Kami to live in an underground cave-like prison. Ma-ō’s underlings then go to the surface and cast evil magic in an attempt to capture children so that Ma-ō can suck their energy away and escape from his prison.

Fortunately, Gurīnman loves children so much that he comes flying down from outer space to save them.

At the end of the first episode, he gives a call button to the children called Gurīn Kōru (グリーンコール, “Green Call”).

The device is shaped like a circle with a large button in the center, similar to Zen-ō’s button, except with a more complicated design. This one has flashing lights on it!

Similar to what Zen-ō says to Goku, Gurīnman tells them, “Whenever you need my help, just push the button.”

True to form, anytime the children are threatened by monsters—which happens every episode—they simply push the button and Gurīnman appears! He then rescues the children and defeats the monster.

Afterward, he jumps into the air and returns to outer space!

This idea of an ultra-powerful being who appears at the push of a button goes on to establish a trope for other tokusatsu series intended for children, where they can summon the hero to their side whenever they are threatened. Similar shows have them summon giant robots that they either control remotely or pilot from inside.

As far as I can tell, Gurīnman was the first to introduce this concept, but there are countless shows just like Gurīnman published throughout the 1970s, ‘80s, and up to today.

Calling Zen-ō

Toriyama portrays this scenario in Dragon Ball Super Episode 67.

In this episode, Goku and Vegeta have exhausted their options in trying to defeat their immortal opponent. Goku reaches into his uniform for a senzu, but instead finds Zen-ō’s button, which he had forgotten about.

He then remembers what the button does and pushes it.

With bright light, Zen-ō appears, defeats the monster, and ‘rescues the children.’

Zen-ō and Goku

Why does Zen-ō give his call button to Goku, of all people, for the first time in the history of the cosmos?

Zen-ō’s defining characteristic is that he is the mightiest being in existence, yet instead of appearing all-powerful, he looks, talks, and acts like a child. That is, until he destroys a universe with the closing of his hand.

He is a prime example of what I call Toriyama’s Rule of Opposites. This is when Toriyama puts contrasting characteristics, themes, or people together, in order to make one trait stand out against another.

Goku is also a contrast of opposites. He is ultra-powerful and loves to fight, yet is the most childlike, pure-hearted, and innocent character in the series.

This similarity of opposites is what draws Zen-ō to Goku. Zen-ō recognizes a trait in Goku that he sees in no one else, and as a result, he chooses to make Goku his friend and gives him the button.

In addition, the classical idea of summoning a deity to provide salvation can only be done by the pure-hearted because they are the only ones fit to receive the gift that allows them to connect with the divine.

This concept hearkens back to spiritual ideals found in Shintō, Buddhism, and Dàoism, that profess a man must be pure of heart in order to find communion with the divine and to attain salvation. It’s only by being pure that you can have a personal relationship with the enlightened and immortal.

According to this school of thought, the goal of self-cultivation is to shed our attachments and defilements in order to become childlike once again, as we return to our original, true selves. Those who succeed gain great supernormal powers and can commune with deities. The higher they ascend up the spiritual ladder, the higher-level deity they can interact with.

Of course, this is what we see in Goku, as he reaches higher and higher levels, up to the point of Zen-ō.

Japanese pop-culture often emphasizes this ideal of a strong yet pure hero who can fight yet remains innocent because it is rooted in their traditional spiritual culture.

As we see in Gurīnman, it’s the innocent children who have the greatest power in the universe, because it’s the children who can summon the servant of Kami (“God”), so long as they are willing to make the choice to call for him.

Thus, Zen-ō giving his call button to Goku is the same idea as Gurīnman giving his call button to the children of Japan.

Eternal Inspiration

Toriyama grows up watching tokusatsu shows and falls in love with them.

As a result, Dragon Ball has countless references to tokusatsu shows throughout the series, from the first few chapters of Dragon Ball in 1984, all the way up to Dragon Ball Super in 2016.

You can read about dozens of examples of devices like this one, as well as transforming heroes, giant monsters, and the lighthearted spirit of this era of Japanese television in my Dragon Ball Culture book series.

It should come as no surprise that Toriyama continues to pull ideas from shows that he enjoys from this era of his life and then adds them to Dragon Ball Super without telling anybody. That’s his modus operandi.

To conclude, the origin of Zen-ō’s button is that it’s a device inspired by the divine ideals of Eastern spirituality, which are manifest in superhero shows for children starring giant divine robots that fight demons, that are then portrayed in the world’s most-recognized anime and manga.

' . $comment->comment_content . '

'; } } else { echo 'No comments found.'; }