Hong Kong Comics Inspired Dragon Ball?

Did Hong Kong comics inspire Dragon Ball? There’s a theory going around in the fan community that they did. But is it true?

On September 16, 2015 there was a Dragon Ball fan who created a lengthy forum post on the fan site Kanzenshuu.com where he attempted to prove that Dragon Ball’s true genre was wǔxiá.

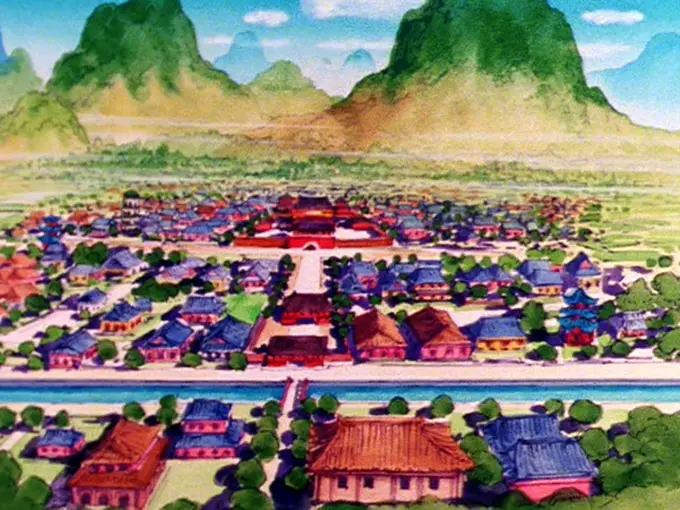

Wǔxiá (武侠, pronounced ‘woo-shya,’ “martial hero”) is a genre of Chinese martial arts novels, films, and comics popular in East Asia and Southeast Asia.

This genre features wandering martial artists who fight one another in a mystical Chinese-style fantasy land. Think “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon,” and you’ll get the basic idea. They usually involve a master swordsman fighting against an assortment of different experts in secret and deadly arts.

Wǔxiá is a rich topic, and to explain its full history is a massive effort. As a result, more detail will have to wait for a future article.

The author of this post, Kunzait_83, argues that Dragon Ball is a wǔxiá series, that Street Fighter is a wǔxiá series, and other pop culture products like them stem from the same source of Chinese culture.

His post is detailed and full of multimedia and impassioned statements, with countless examples of different movies, character archetypes, and supernormal kung fu that are found in each medium. He then shows you the origin of the wǔxiá genre, and of each series, and compares them to Dragon Ball. He shows examples that predate Dragon Ball (1984) as proof that Dragon Ball was inspired by them. He also shows examples that postdate Dragon Ball, for further examples of how the genre has evolved.

Kunzait_83 admits he isn’t a scholar. Nonetheless, he presents direct similarities that are hard to ignore. As a result, there are now fans in the Western fan base who believe Akira Toriyama intended Dragon Ball to be a wǔxiá manga from the start.

I was blown away after I read his article because I thought I had Dragon Ball figured out. I make my living by studying Dragon Ball’s culture and writing about it, and then all of a sudden this new theory comes along that attempts to explain the entire series in a new light. And it makes sense. It just clicks. It feels right. It’s like a ‘theory of everything,’ or a universal theory of physics, and you’re just pulled into believing it.

As a result, I was driven to discover the truth. I wondered, ‘Is Dragon Ball wǔxiá?’

Digging Deep

I’ve spent the last 6 months researching wǔxiá, Hong Kong cinema, and Hong Kong comics. I’ve read every scholarly and non-scholarly article I can find on the subject, including the only book that’s ever been published in English, titled Hong Kong Comics: A History of Manhua (2002), by Wendy Siuyi Wong.

I’ve read all of the comics that Kunzait_83 cites as sources. For example, Dragon Tiger Gate (龍虎門, aka “Oriental Heroes,” 1975) and The Force of the Buddha’s Palm (如來神掌, “Buddha’s Divine Palm,” 1982). I’ve also watched hundreds of kung fu and wǔxiá movies, including the ones he mentions in his post.

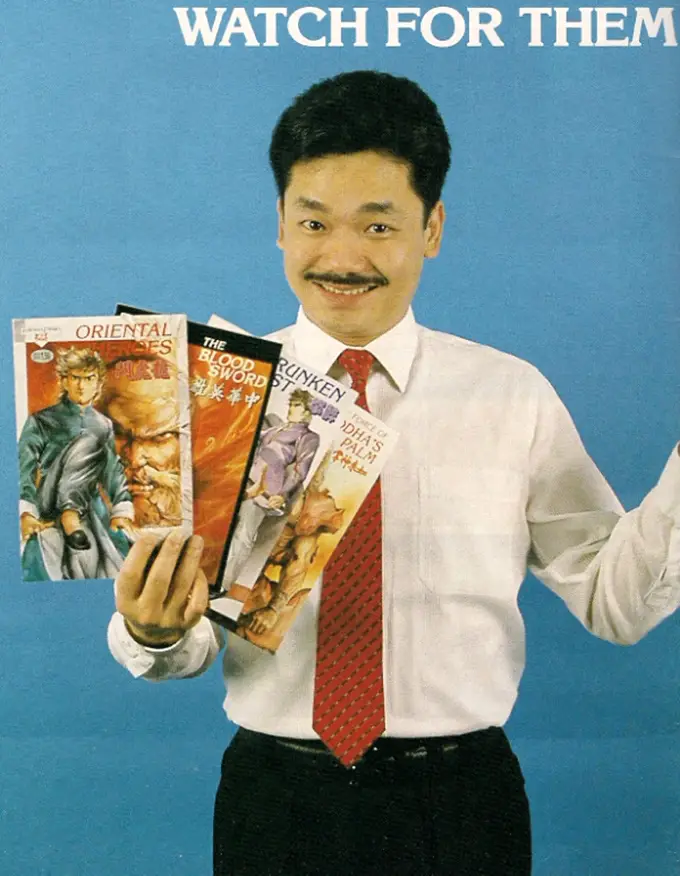

Beyond that, I contacted experts in Hong Kong comics and East Asian culture from around the world and asked them to weigh in on the topic. This includes the actual creators of these comics; namely, Tony Wong and his associates. Tony Wong is the ‘Godfather of Hong Kong comics,’ and a veritable ‘Stan Lee of East Asia.’ He created the entire industry.[1]

And as if that weren’t enough, I reached out to Akira Toriyama and his editor, Kazuhiko Torishima, through my contacts at Viz, who I asked to forward my request to Shueisha.

After all was said and done, only a few experts replied, and the people at Viz and Shueisha never responded.

That means I was on my own and had to blaze my own trail in this area of research that has never been conducted. I wanted to know, is it possible to connect Hong Kong comics and Dragon Ball?

The Verdict

In the end, while I can see the similarities in the combat, the characters, and in rare cases the plot, I find it impossible to agree with Kunzait_83’s main argument that Dragon Ball is a wǔxiá series, and in particular that it’s inspired by Hong Kong comics. This is because the argument he’s making is broad, consists entirely of circumstantial evidence, and unfortunately has no citable proof to back it up.

I’ve spent months writing articles that I intended to publish in my books that breaks all of these different subjects down and explains them in a way that’s easier for a novice to understand. But it is extremely challenging, and I’ve discovered that the topic could be a book unto itself. I had to stop because it’s an insurmountable task at this point in my production schedule.

So while I’d love to address all of Kunzait_83’s claims at once in a massive post, instead, what I’m going to do here is focus on a single subject. That is, Hong Kong comics. And in particular, the claim that Akira Toriyama used these comics as a source of inspiration in creating Dragon Ball.

The primary issue at hand is the supernormal Chinese martial arts which are dependent on qì (氣, Japanese: ki, 気, “energy”), and strengthening the mind-body connection to pull off incredible feats. These include supernormal speed, power, toughness, projection of external energy as a weapon, self-powered flight, energy healing, supernormal vision, cross-dimensional travel, and so on.

Intro to the History of Hong Kong Comics

Most of my readers are fans of Japanese comics and anime, and likely have not read Hong Kong comics. Even I wasn’t familiar with them until I started researching wǔxiá in greater detail. So here’s a brief history lesson to provide context.

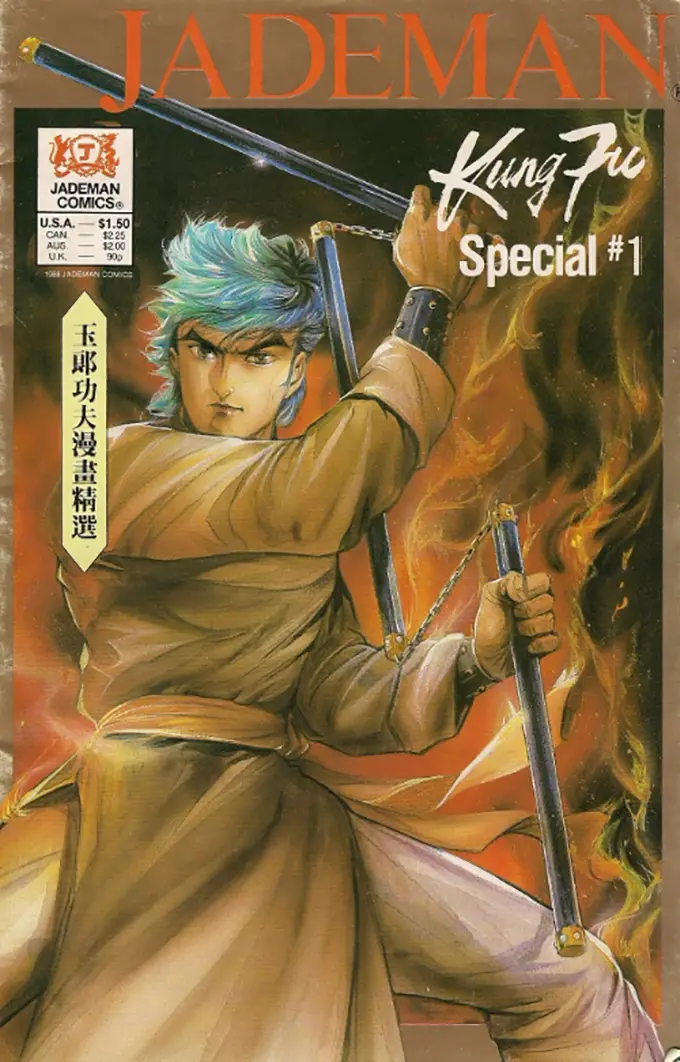

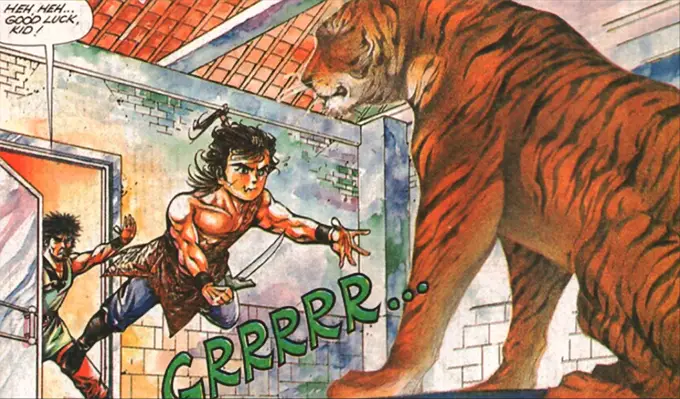

For the sake of keeping it brief, I’m just going to show you a few examples of the comics that have similar elements to Dragon Ball. In particular, the martial arts comics of the 1970s and early 1980s. These are what Kunzait_83 uses as examples, and they’re also the most famous and primary examples of the medium.

These comics were directly inspired by Hong Kong cinema, which boomed in the early 1970s thanks to Bruce Lee. After Lee’s death, there was a huge surge in production by the Shaw Brothers and Golden Harvest companies. During the 1970s and early 1980s, these two companies made over 1,000 kung fu films. They were a lucrative business, and the comic creators were so inspired by them that they decided to create their own comic style equivalent.

They then combined the movie archetypes and tropes with wǔxiá archetypes and tropes, while exaggerating the supernormal aspects. For example, Tony Wong says in the description to The Force of Buddha’s Palm, “The Force of Buddha’s Palm is my attempt to bring a novelistic approach to the comic book. Similar in tone to traditional Chinese kung fu novels, the The Force of Buddha’s Palm combines exaggeration of movement with modern animation techniques to bring the story alive in a visually exciting way.” By ‘Chinese kung fu novels’ he’s referring to wǔxiá novels.

These comic creators were also directly inspired by Japanese manga.

In the early 1960s, Japanese manga had not yet reached Hong Kong in an official format. However, the pirated Taiwanese editions of manga became incredibly popular among children. The manga reached Taiwan, had its text whited out, and was then rewritten with Chinese lettering. After that they were shipped to Hong Kong and neighboring countries. Other times the manga were redrawn by local artists and passed off as original works without any mention of the Japanese creator’s names. For example, Chaoren Zhizi’s The Son of Ultraman (1969) was a faithful recreation of the Japanese television program, turned into a Hong Kong comic. There were similar equivalents of Astroboy and Tetsujin-28, all of which were illegal.

There were no copyright laws in Hong Kong, nor official deals in place for legitimate copies until the mid-1990s. In addition, the Japanese did not enforce their copyright outside of Japan, so Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Southeast Asian countries were flooded with hundreds of thousands of illegal comics for the next 30 years. In fact, 100% of all Japanese manga in these countries was illegal.[2]

These pirated copies cost 10 cents per volume, compared to the 20 cents of their home grown competitors, and they included twice as much content. As a result, they were much more popular. The young children and teenagers of Hong Kong read these illegal manga and became inspired by them to create their own. The question was, what to write?

Seeing the ensuing boom in martial arts movies, the young authors in question decided to emulate these stories in comic book form. But since they were raised on Japanese manga, they also incorporated many elements from manga. For example, the use of Japanese / Chinese written characters for sound effects, the variety of speech bubbles, speed and motion lines, visual cues, and above all, long-form storytelling with plots that can last for dozens of chapters. Indeed, much of what we call Hong Kong comics is an emulated Japanese manga.

The main difference is the art style, which is the result of an evolution of mainland Chinese artists fleeing to Hong Kong during the Chinese Communist revolution, and then being influenced by American comics that were also illegally published on the island in the 1950s and ‘60s. Of course, this changed in the 1980s, as more artists copied the popular style of Ma Wing-shing (馬榮城), author of the best-selling Chinese Hero (Zhōnghuá yīngxióng, 中華英雄, 1982) comic, who himself emulated the Japanese artist, Ikegami Ryōichi, among others.

The end result is a style that is both Western and Eastern, with realism at the forefront and a vivid use of color. This contrasts against the black and white Japanese manga, with its big-eyed characters that are full of expression. But what these martial arts comics have in common is the action and adventure.

Examples of Hong Kong Comics

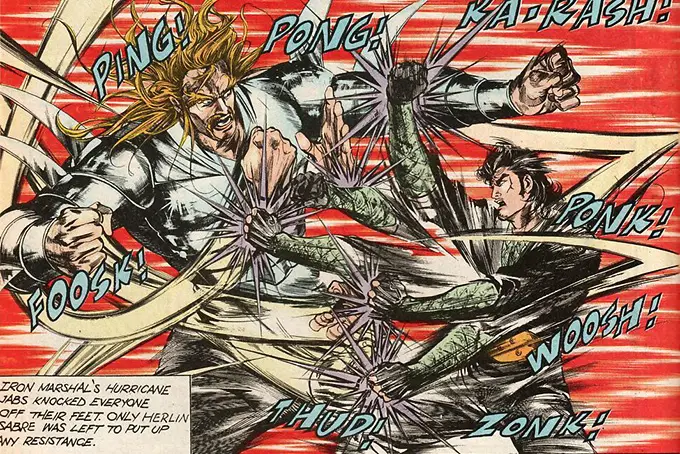

Now let’s look at some examples of these supernormal powers in action.

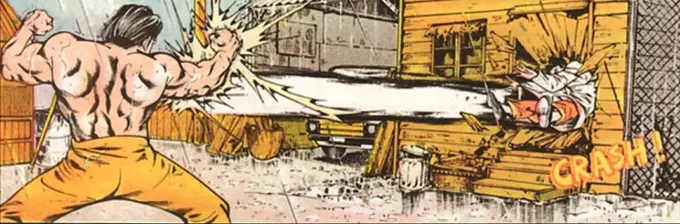

Super strength:

Oriental heroes:

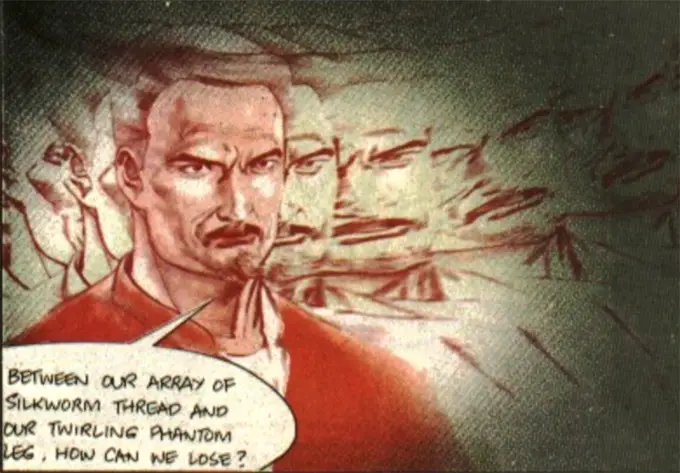

The Force of the Buddha’s Palm:

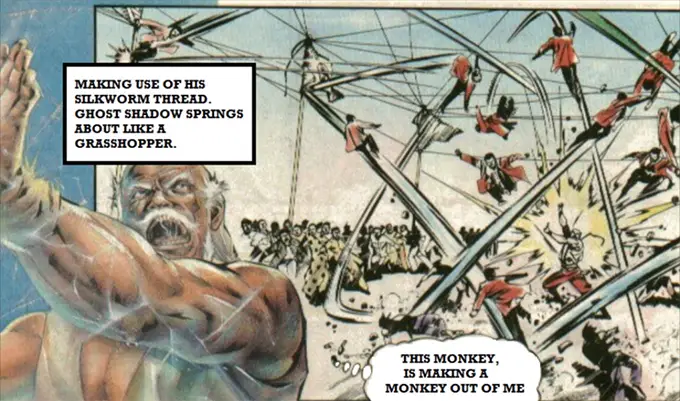

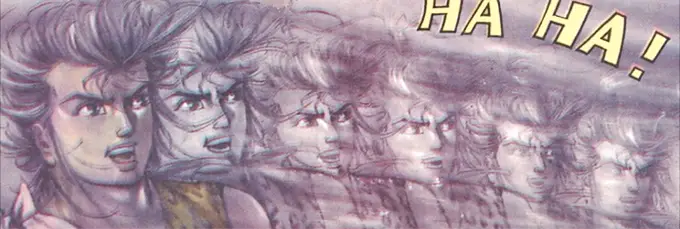

Super speed:

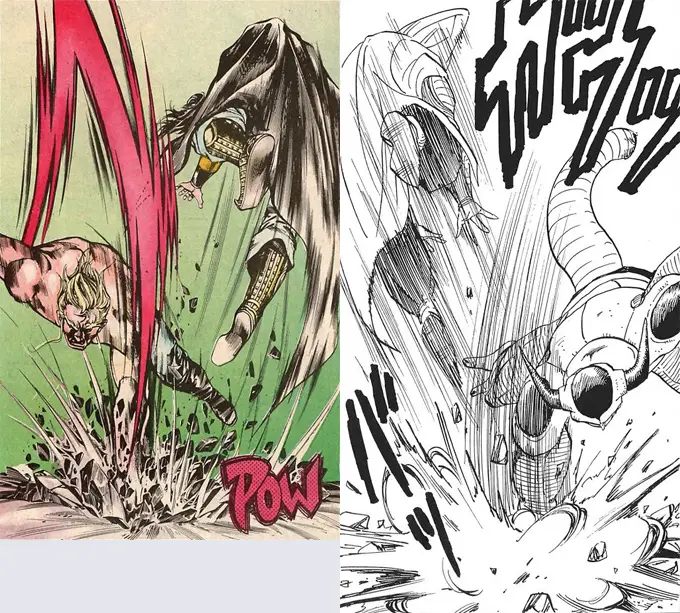

Oriental Heroes:

The Force of the Buddha’s Palm:

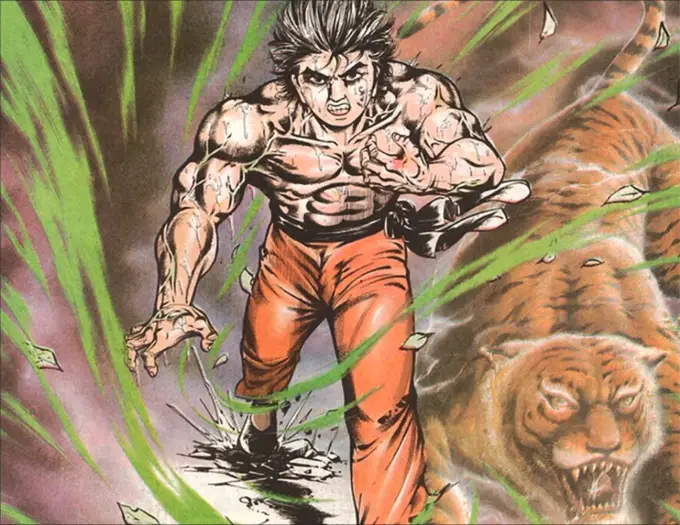

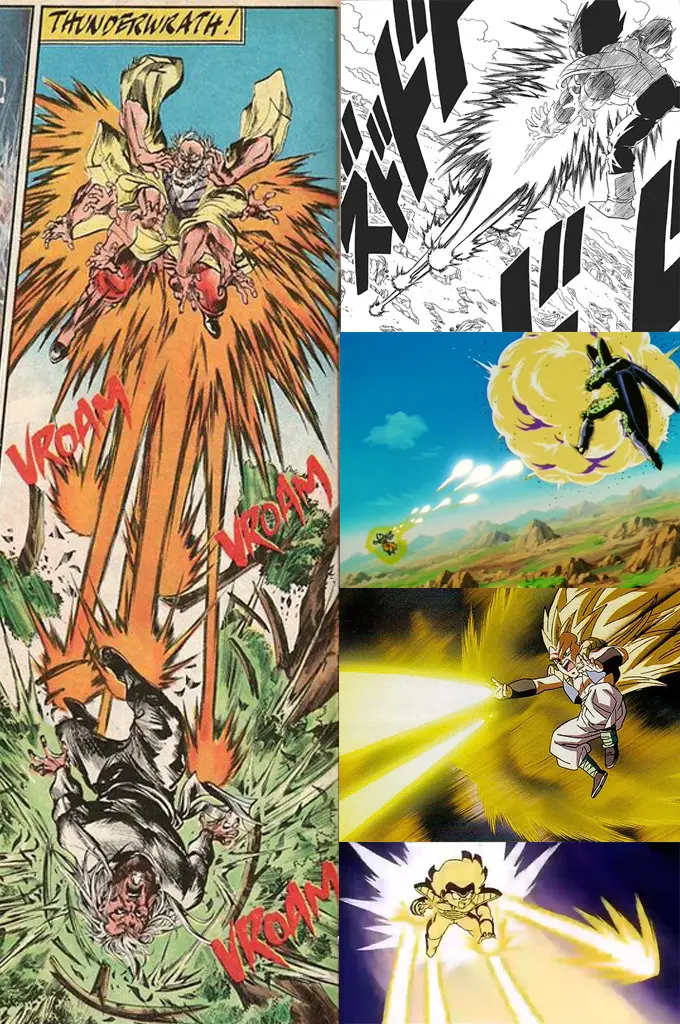

Powering Up and Transforming:

Energy healing:

Blood Sword Dynasty (Chinese Hero):

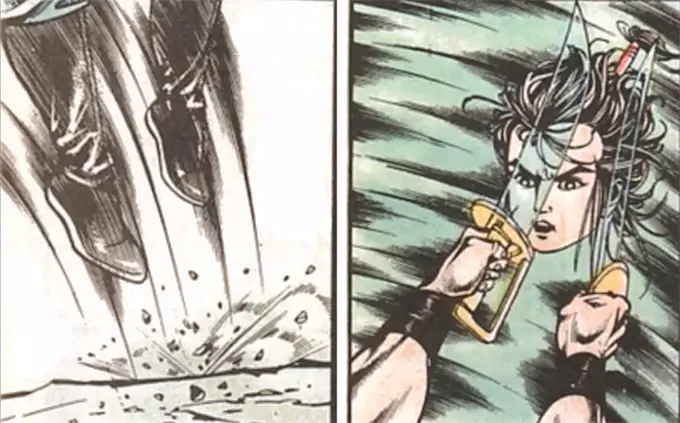

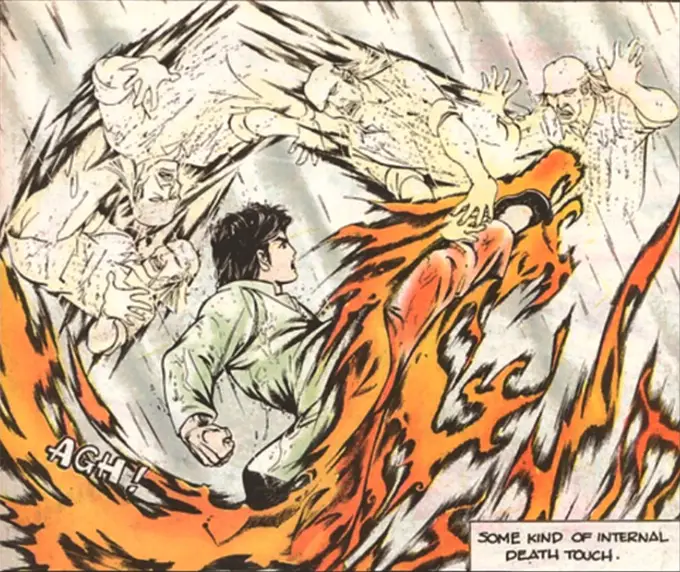

Side by Side:

These two are from Iron Marshal (1989), compared to similar actions in the Dragon Ball Z portion of the series, from 1989 onward.

All in all, the visual similarities of these battles and techniques is strong. This is why it’s so tempting to assume that these comics lead to Dragon Ball.

However, most of the plots are different, and involve Chinese heroes fighting against evil Japanese organizations, or they involve fight after fight with little comedy or Dragon Ball style escalation. Above all, no science fiction and fusion-style writing like we find in Toriyama’s masterpiece. So Toriyama certainly wasn’t emulating their writing style.

The one big exception regarding the plot that I’ve found is in The Force of the Buddha’s Palm Volume 5. Here, a young boy named Devilito is raised by a group of murderous men in the Valley of Ten Demons; assassins who specialize in different techniques, from brute force to necromancy. He is forced to survive in the wilderness, kill wild animals, and overcome do-or-die scenarios. This sounds a lot like what happens to Gohan when he has to survive in the wilderness and is trained by the demon, Piccolo.

In one encounter, Devilito uses a technique similar to Muten Roshi’s multiple zanzō-ken (“after image”) technique, where he moves at such great speeds that he appears to be everywhere. He uses this to dodge around his uncle, who is trying to catch him and possibly kill him, ala Piccolo against Gohan.

Later, he avoids the uncle’s deadly qì-powered drill hand by plunging into the earth using his qì powers, and then reappearing behind his uncle and kicking him in the back. It’s just like when the characters in DBZ are submerged in the earth, but then reappear later behind their opponent and burst out of it with an attack.

Likewise, Devilito’s brother Samsun, who is separated at birth, uses the zanzō-ken style technique to avoid an evil martial artist’s punch. The punch passes through the phantom image of Samsun, and the man exclaims, “What the hell’s goin’ on?” Then in the next frame the boy is behind him. “Hey, bozo! I’m over here!” It’s exactly like in Dragon Ball, when Goku does similar things.

And we also find a similar technique in Blood Sword Dynasty, showing that it’s common throughout the genre.

As you can see, the similarities are there, so the big question then, is ‘did Akira Toriyama read these Hong Kong comics?’

I argue there is zero chance that Toriyama read these comics because the Japanese publishing industry didn’t give a crap about them.

One-Way Traffic

Hong Kong comics owe their existence to Japanese comics. Professor Ng Wai-ming writes in International Journal of Comic Art, “The relationship between Japanese comics and Hong Kong comics has been largely one-way traffic. … The history, art, industry, and culture of Hong Kong comics have all been under the spell of the Japanese.”[3]–[4]

Professor Ng is a leading expert on the study of Hong Kong comics and Japanese popular culture. He is a Chair in the Department of Japanese Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. When I asked for his opinion on the matter in question on March 5, 2016, he replied via email: “I don’t think Hong Kong comics have any influence on Dragon Ball. Of course, the story was inspired by the Chinese classic Journey to the West, and in its combat you can see some influence of Chinese martial arts, but these are not directly related to Hong Kong comics.”

Kunzait_83 argues that Journey to the West is likewise a wǔxiá story. But I don’t agree. Journey to the West is a folk tale based on a real-life Buddhist monk that became increasingly exaggerated as time went on. While it does have a lot of supernormal characteristics, it is in no way about a wandering martial artist who fights to become stronger. It’s about a Buddhist monk on a trip to India to recover sacred texts. Yes, there’s lots of fighting and other paranormal activity, but that only happens out of necessity while defending themselves along the journey. Most importantly, wǔxiá didn’t exist as a genre when the story was published in 1592, and the author did not intend it to be a wǔxiá story. So the term should not (and I believe cannot) be retroactively applied with a 20th century mindset. Alas, that’s a topic unto itself.

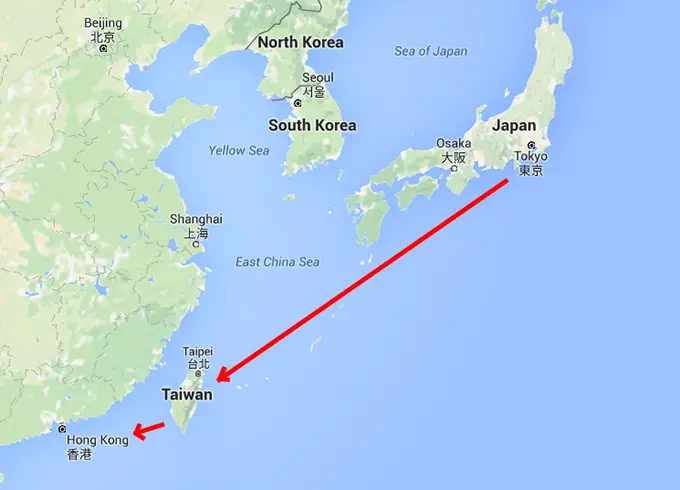

Back to the point—Japan is the origin of comics in East Asia. Throughout the 20th century the cultural flow of comics traveled from Japan to its neighbors of Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Korea. From there they would spread to China and Southeast Asia via pirated copies, including Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Indonesia.

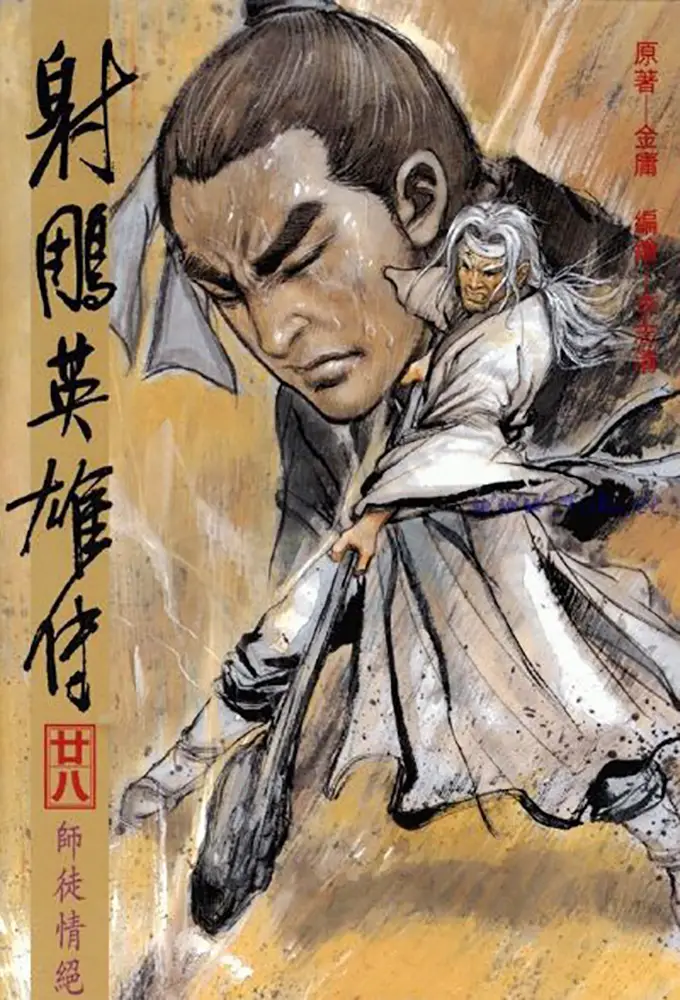

This cultural flow never flowed the other way. Hong Kong comics were never published in Japan prior to or during Dragon Balls serialization, from 1984 to 1995. The first Hong Kong comic to be published in Japan was The Legend of the Condor Heroes (射雕英雄傳, Chinese publication date of 1998) by Lee Chi Ching (Chinese: 李志清, born 1963). This comic is a popular adaptation of wǔxiá author Jīn Yōng’s novel The Eagle Shooting Heroes (射雕英雄傳, Shè diāo yīngxióng chuán, 1957). This is a genuine wǔxiá comic, and it’s one of many based on the same novel.

Never in the 20th century did the Japanese look to Hong Kong as a source of inspiration. It was always the opposite, as Hong Kong looked to Japan for inspiration in their art, storytelling, and genres. The martial arts comics mentioned in this article only existed in the first place because their creators read illegal copies of Japanese comics and became inspired by them to the point of making their own. They then combined manga with kung fu films and occasional wǔxiá films. In turn, this created a new industry.

In all of my research I have not found a single example of Hong Kong comics influencing Japanese comics. And I’ve purposefully searched for them. Instead, it is a well-established fact that the opposite took place. Only in the mid to late-1990s did Japanese manga publishers begin to recognize original comics outside of Japan’s borders. And still today, it’s a rare occasion when a non-Japanese creator will be asked to collaborate on a manga. The exception is when a Japanese company tells a Hong Kong or Korean artist what to do with their licensed adaptation, such as for a comic about a video game, ala Street Fighter.

So to argue that Akira Toriyama read a select few Hong Kong comics prior to or during the creation of Dragon Ball and was so inspired by them that he decided to change his story to emulate these comics is a groundless claim. Not only were the comics not available for him to read, but even if they were, Toriyama does not read or speak Chinese. In addition, he has said several times in his interviews that he was too busy to read his fellow authors works in Japanese, so how would he find time for these Hong Kong comics in Chinese?

You might be thinking, ‘It’s possible that someone at Shueisha picked up copies of these comics on a business trip to Hong Kong, took them back to the office, and showed them to Toriyama, saying, ‘Make them like this!’’ I’ve considered this, but not only is that a far-fetched theory, there isn’t a shred of evidence to back it up. And it also ignores the fact that in the 1970s and ‘80s the Japanese disliked the Chinese and in no way wanted to copy what they were doing. Actually, the Japanese were rather elitist about their comics’ superiority, and would have made it a point to not copy from Chinese comics.

Furthermore, in the over 170 official interviews with Toriyama, his editors, and the producers, actors, and staff of the anime, none of them has ever mentioned Hong Kong comics, nor the Chinese novels they are sometimes based on. You’d think that if these comics were such a large influence on Dragon Ball, that someone would have mentioned them at least once in the last 30-plus years, right?

So on whether or not we should regard this theory as plausible, Professor Ng adds, “The best way is to ignore this ridiculous view.”

Parallel Development

How then are we to explain the similarities between Hong Kong Comics and Dragon Ball?

The most logical argument is that Hong Kong comics and Dragon Ball were influenced by the same sources of Hong Kong cinema.

It’s a case of the Hong Kong movies inspiring Hong Kong comics, and then later on in a separate country, the Hong Kong movies partly inspiring Dragon Ball. Not a case of the ‘Hong Kong movies’ leading to ‘Hong Kong comics’ leading to ‘Dragon Ball.’ There is no direct connection between Hong Kong comics and Dragon Ball.

For example, Toriyama has cited Jackie Chan’s Drunken Master (醉拳, 1978) and Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon (1973) as the two main sources of inspiration on the creation of Dragon Ball. Without these movies, Dragon Ball wouldn’t exist. In contrast, he has never once cited Hong Kong comics or any wǔxiá film in particular.

However, with that said, there are hundreds of films that had an influence on Dragon Ball that Toriyama does not mention by name. This is why I was so open to Kunzait_83’s theory in the first place. There’s a ton of Hong Kong films that influenced his work, but also many Hollywood films, Japanese movies, and TV shows. I reveal these connections in great detail in my Dragon Ball Culture book series.

For example, Dragon Ball episode 81 is titled Gokū · Makai e Iku (悟空·魔界へ行く, “Gokū Goes to the Demon Realm,” September 30, 1987). In this episode Goku visits the Demon Realm and fights against Shura, a demon king. Well, it turns out that Shura’s appearance is directly inspired by a demon in the movie Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain (新蜀山劍俠, 1983), by director Tsui Hark.

The anime staff lifts his appearance straight from the film. They then turn him into a young and cocky man with a 1980’s clothing style mixed into his robes. And this is just one of countless examples of how Hong Kong cinema influenced the series.

Nonetheless, Hong Kong comics were not a source of influence because 1) the Japanese didn’t care about them, and 2) Toriyama would never have had a chance to read them.

To argue that they were a big source of influence when there is no concrete evidence, only circumstantial, is a fools errand, because there is no way to prove it. I tried for months, and I wanted to believe it was true, but it’s not. And on top of that, experts in the field of Hong Kong comics disagree with the very notion.

While I’ve only addressed Hong Kong comics in particular here, the root of Kunzait_83’s argument that Dragon Ball is intended to be a wǔxiá series is also flawed. Not because it’s 100% wrong, but because Dragon Ball is a combination of countless different influences, and kung fu movies is only one of them, with wǔxiá being a subset of those films. You can argue that it’s a kung fu inspired series, for sure, but not that Toriyama intended it to be a wǔxiá series. The similarities are mostly by happenstance as he made the story up week to week. In part, through his subconscious sublimation of countless tropes and character archetypes as a result of watching thousands of hours of these films as he drew each chapter.

I’d love to explain this in further detail, and I’ve tried writing it, but it’s a daunting task, just like Kunzait_83’s original post, and it would be a really long, multi-part post that would delay the publication of my books. Of course, sales of those books are what allow me to keep doing this full time, so I have to prioritize.

In any case, in the last 6 months I have collected an enormous amount of research material on Hong Kong pop culture, and there is literally an entire book’s worth of more content that I could share with you. So if you like reading about the influence of Hong Kong culture on Dragon Ball, then let me know what you want to hear!

Ultimately, only Akira Toriyama and his editor know for sure. So what do you think of this issue? Would you say Dragon Ball is inspired by Hong Kong comics or wǔxiá?

Footnotes

[1] Read more about Tony Wong: http://www.tcj.com/this-week-in-comics-7214-a-beginners-guide-to-jademan/

[2] “A Comparative Study of Japanese Comics in Southeast Asia and East Asia,” International Journal of Comic Art (New York), Vol. 2. No. 1, Summer 2000, pp. 45-56. http://www.cuhk.edu.hk/jas/staff/benng/publications/doc05/02.pdf

[3] Professor Ng Wai-bin’s Info:http://www.cuhk.edu.hk/jas/staff/benng/ and http://www.jas.cuhk.edu.hk/en-GB/people/prof-ng-wai-ming-benjamin, plus a list of further publications

[4] “Japanese Elements in Hong Kong Comics: History, Art and Industry,” International Journal of Comic Art, 5:2 (US) (Fall 2003), pp. 184-193, available here: http://www.cuhkacs.org/~benng/Bo-Blog/read.php?456 and here: http://www.cuhk.edu.hk/jas/staff/benng/publications/doc110/jpn-element-in-hk-comic.pdf

' . $comment->comment_content . '

'; } } else { echo 'No comments found.'; }