The Origin of the Tenkaichi Budokai

http://youtu.be/x2exacC3KwY

Have you ever wondered where the idea of the Tenkaichi Budokai came from? Did Akira Toriyama think of it himself, or did he “borrow” it from somewhere else?

This article will reveal the true origin of the Tenkaichi Budokai, and you’ll never see it the same way again.

Re-Translating Tenkaichi Budokai

The standard translation of Tenkaichi Budokai (天下一武道会) by FUNimation is “World Martial Arts Tournament,” but this strips the deeper cultural meaning of the term away. That’s why I’m going to re-translate it and explain its etymology.

Tenkaichi (天下一) is a combination of 3 Japanese Kanji based on the Chinese Hanzi.

Ten (天) means Heaven, and refers to the Upper Realm where the Buddha’s, Dao’s and Gods live in the Chinese pantheon, and is the same Heaven that the characters refer to in Dragon Ball.

Ka (下) means Below, and is the character for One (一) with a line below it. The One character by itself refers to the unification of all things in Heaven, a period of time before the duality of Yin and Yang. Once Earth was created there then existed an “Above” and “Below,” so anything Below (Heaven) is described with Ka, and simultaneously means “on the Earth.”

Ichi (一) means One and refers to a singular unification or simply the number one.

So Tenkaichi (天下一) really means “Number One Under Heaven.”

Budokai (武道会) is also a combination of 3 Japanese Kanji based on the Chinese Hanzi.

Bu (武) is the single character that epitomizes the Martial Arts, including martial ethics, techniques and history.

Do (道) is the Way, or Path. It’s a transliteration of the Chinese Dao (道). It implies a spiritual path or journey for practitioners, and when combined with Bu becomes Budo (武道), the Way of the Martial Artist.

Kai (会) means a gathering or conference under one roof. It’s a moment where people or things are brought together.

So Budokai (武道会) really means “Martial Arts Practitioners Gathering,” or “A Conference of Those Who Walk the Martial Path.”

Thus a more accurate translation of Tenkaichi Budokai (天下一武道会) is “The Number One Under Heaven Martial Arts Gathering.”

I feel that saying “World Martial Arts Tournament” is a disservice to the original meaning of the term, because even if it does describe the external event, it strips away the internal cultural and historical depth that’s implied by Toriyama’s usage.

Toriyama didn’t write Tenkaichi Budokai in Japanese Katakana or Hiragana, or in English like he has with other aspects of Dragon Ball. He purposefully wrote it in Kanji to reference the Chinese history, just as he did with Shenron (神龍) (Chinese: Shenlong), the God Dragon. This is important to understand properly because it’s something the Japanese audience would automatically grasp as a result of living in Japanese society, but has heretofore been lost on foreign audiences.

It will also help you understand the historical and cultural context of the following sections.

Ancient Battleground

The Tenkaichi Budokai is not a normal tournament. It’s a global, mixed martial arts event where anyone is able to enter regardless of age or weight, where there is no protective gear, and where only the most expert of warriors fight until knocked unconscious.

That’s so rare it seems like fantasy.

But as with many other aspects of Dragon Ball, I’ve traced it back to an historical predecessor in ancient China.

To briefly bring you up to speed on East Asian martial arts history; The martial arts spread from India to China and then continued through Korea to Japan. The dispersal of techniques and systems occurred over thousands of years, and due to differences in culture and location produced a huge variety of styles. This bred conflicts and eventual rivalries between schools and even kingdoms in the war of martial arts superiority.

The most famous martial schools in China are the Shaolin Temple to the North and the Wudang Temple to the South. There are also the Emei Temple, Guang Dong Temple, Fu Jian Temple, and dozens of famous family styles. According to Master Eric Ling in the documentary Needle Through Brick (2008), “There are over 600 different styles of Kung Fu in the world.”

This huge variety of styles was ripe for competition. Statements such as, “My style is better than your style,” and “Your Kung Fu is no match for mine,” are easy to imagine being said by prideful fighters. These phrases even became cliché in Hong Kong Kung Fu films during the 70’s and 80’s, and these are the films that inspired Akira Toriyama to create Dragon Ball and Goku’s character, based partly on Jackie Chan in Drunken Master (1978).

How did they settle their disputes?

Firstly, on the battlefield.

Secondly, through challenges and tournaments to determine “The Number One Under Heaven.”

These challenges and tournaments were held on the Lei Tai.

Lei Tai – The Thunder Hand Platform

The Lei Tai was the ancient Chinese precursor to the Tenkaichi Budokai.

A Lei Tai (Chinese: 擂台, Traditional: 擂臺) is a raised platform without any ropes or walls, where martial artists compete for supremacy.

No divisions or classes. No pads. No time limits. No restrictions. Just two opponents on a raised platform, fighting to the death.

The first one to be knocked unconscious, surrender, be thrown from the platform, or die, is the loser. The winner remains as the “platform occupier” and waits for another challenger to appear.

Lei Tai dimensions vary depending on historical time or location, but could for example be 24 feet square and 3 to 6 feet tall, or in some cases circular.

What makes the Lei Tai so unique is that you could fall off or be thrown off at any time. Because there are no ropes or walls you must be an expert at either holding your ground or at evading attacks. It is inherently more dangerous, as a misplaced fall or displacement from the ring could lead to serious injury. The smaller the ring, the more intense the conditions.

The Lei Tai was also a form of entertainment.

Martial artists would travel to foreign cities, set up a Lei Tai, and issue challenges while selling tickets. The longer they could stay on the platform and the more challengers they beat, the larger the crowds. People would place bets on the outcomes and root for their local champions. As a result, rigged bouts were not unheard of. These matches were for sport and likely didn’t end with death, as murder was a punishable offense often paid for with execution in the town square. Even so, rivalries between towns, martial arts schools, or different clans did occur.

The etymology of Lei Tai, like Tenkaichi Budokai, is equally significant.

The first character (擂) (Chinese: Lei, Japanese: Rai) combines the radicals for “[striking] hand” with “thunder” and is often translated as “to beat” with the hands. The second character (臺) (Chinese: Tai, Japanese: Dai) shows a man standing on a stage, and means “platform,” so Lei Tai literally means “[striking] thunder hand platform.”

From a cultural perspective Lei Tai meant “martial arts ring” as the term was synonymous with fighting.

The Lei Tai was a part of Chinese culture for thousands of years and it was the place where martial artists gathered.

It was also the place where open tournaments were held that allowed any and all competitors to fight their way up the ladder. The cream would rise to the top and the winner would be declared champion, given respect in the community, or honored with a position as bodyguard to a nobleman or even the Emperor.

Ancient Examples of Lei Tai

Where did the idea of Lei Tai come from?

Like many of the Eastern martial arts it seems to have originated in India and spread east over the millennia.

There is a related fighting platform in India known in the Malayalam language as the Ankathattu. According to Indian tradition it was a raised platform six feet off the ground where local quarrels would be settled by a duel to the death. If there was an argument, rivalry, or feud that needed to be settled, the local rulers would send their best fighters (an Ankachekavar, or Cekor) to the platform, and the victor would win the argument for his master.

The Ankathattu comes from Kerala, India, the attributed birthplace of Bodhidharma and much of the Vajramukti martial system, which was the precursor to Quan Fa, Shaolin Gong Fu, and a vast portion of Chinese martial arts styles. The martial art used was most often Kalari, the 4,000 year old source for many East Asian arts and one that is still practiced today as Kalaripayattu (Battlefield Gymnasium). It’s probable that like the Vajramukti to Quan Fa evolution, the Akathattu would be a source for the Lei Tai.

This precursor to the Lei Tai may have appeared as early as the Qin Dynasty (221 BC – 206 BC). But its earliest recorded use was in the Song Dynasty (960 AD – 1279 AD) and was part of traditional Chinese society thereafter.

For example, a Lei Tai bout was depicted in Outlaws of the Marsh (one of the Four Great Chinese Classics), that details the experiences of 108 noble outlaws during the Song Dynasty. The book was written by two natives of Zhejiang, a martial arts hub of eastern China. Outlaws of the Marsh, like Journey to the West, has been a source of inspiration for many works of literature, films, anime, comics and video games, including Dragon Ball, with its bandits and high flying martial artists.

As the martial arts traveled eastward the Lei Tai was most likely a cultural export of the Tang Dynasty (618 – 906 AD) into Japan. I contend that this can be seen in the 1,000 year old Japanese martial art of Sumo, a sacred Shinto art where wrestlers try to push or throw one another off the platform.

The Lei Tai’s history continues in a line from ancient India, to ancient China, and then Japan, right on up to the 20th century where we eventually see it in Dragon Ball.

20th Century Examples of Lei Tai

There are a couple of examples of the Lei Tai in the 20th century that are relevant to Dragon Ball.

The first is an individual Lei Tai match between rival schools.

In the book Chen Style Taijiquan: The Source of Taiji Boxing (2001), it retells a story of a Lei Tai challenge. An enthusiastic scholar named Li Qinlin wrote about the benefits and beauty of Chen style Taiji in the Beijing Times newspaper. Beijing’s martial artists were not familiar with Chen style, but had proficient Yang style masters. The article ended with a suggestion that people “try it out” since a skilled 18th generation Chen descendent had recently arrived in Beijing named Chen Zhaopei.

While well intentioned, the article was perceived by other martial artists as an open challenge. Unbeknownst to Chen.

Chen was soon approached by a man who wanted to “test” his Kung Fu. Because there were so many challengers, he was urged to build a Lei Tai in order to formally duel them. Over the course of 17 days he defeated over 200 opponents. With the renown earned from the bouts, Chen established a school and revived the practice of Chen style Taiji as a martial practice.

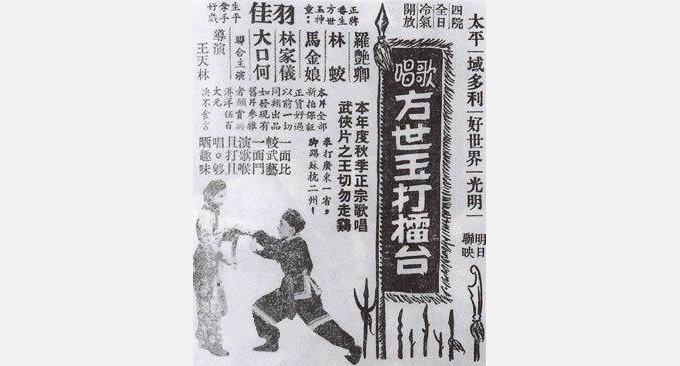

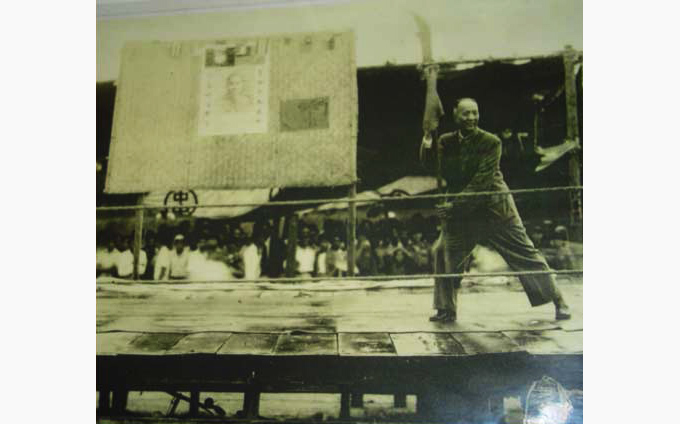

The second instance of a Lei Tai in the 20th century was a grand tournament held in Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, from November 16 to 27, 1929. It was called Zhejiang Guoshu & Entertainment Gala, and was popularly dubbed “The National Lei Tai Tournament.”

Invitations were sent out to all the major martial arts masters and schools across China, and around 240 practitioners came to the fight. Tens of thousands of people attended the Gala every day, including Japanese, Russians, and Americans, although no foreigners chose to fight once they saw the competition. They took photographs instead.

There were no weight classes or divisions, so they divided the 240 warriors into 4 groups. To decide the order of competition, numbers (presumably 1 to 60) associated with each fighter were written on wooden balls and placed into a copper globe. The supervisors shook the copper globe and chose the wooden balls at random. The numbers that came out determined the order of the fights.

For example, number 15 would fight number 34, and so on, until all 60 balls had been selected. Then they would add their names to the fighting bracket and the tournament’s match ups for the day would begin.

For this Lei Tai tournament a simple rule was put into place.

No attacking the eyes, throat, or groin. Everything else was legal.

Matches began with the beating of drums, cymbals and the bang of a gong, and were fought on a Lei Tai made of stone. One match lasted more than 10 minutes, and another lasted for more than 60 rounds of combat.

At the end of the first day there were a lot of head injuries and the atmosphere was tense.

In one powerful matchup, Cao Yanhai fought the famous Iron Palm master from Shanghai, Liu Guosheng. Liu had close to 3,000 students and had also perfected Hard Qi Gong, meaning he could strike with deadly force. Liu began the match by striking Cao with the Iron Palm and paralyzing half his body. Cao’s body went numb but he remained calm under pressure. He quickly changed tactics and became evasive, dodging all of Liu’s mighty blows, while offering his own low sweeping kicks in response. As he regained composure he eventually found his opening and struck Liu with a well-placed punch, knocking him out.

The tournament was so intense that two masters were killed. The finals were called off for concern of losing any more national treasures, and the winners were determined by votes from a jury.

It was genuine Kung Fu fighting at its best. Modern Xingyi Quan master Zhang Hongjun of Beijing has described the event, saying, “What does it mean to have gongfu? The 1929 Lei Tai tournament in Hangzhou is a classic example of how we should understand the term ‘gongfu’.” It served as a national examination of elites and is regarded as one of the most significant gatherings of martial artists in world history.

Another Lei Tai tournament was held 4 years later in Guangdong Province, where a new notice stated, “If death occurs as a result of boxing injuries and fights, the coffin with a body of the deceased will be sent home.”

The Hangzhou tournament was a real world Tenkaichi Budokai.

Keep these two examples of Lei Tai in mind as you see how Akira Toriyama used Lei Tai in Dragon Ball.

Lei Tai in Dragon Ball – Challengers and Rivals

The Lei Tai has appeared in Dragon Ball in several places, but you may not have recognized what it was since the Lei Tai is a fairly unknown thing outside of East Asia.

Before we get to the Tenkaichi Budokai itself I want to show you a few other places it shows up.

The first example is in episode 80 of Dragon Ball, titled “Goku Vs. Sky Dragon.”

In this episode Goku enters a very Chinese looking city where two schools of Chinese martial arts are feuding before an annual competition. Sky Dragon of the Panther-Fang School and Master Chin of the Chin-Star School are scheduled to fight in an annual Lei Tai match to determine “The Master of Martial Arts,” but Master Chin is ill. It’s an important match to win because Sky Dragon has intimidated all of Master Chin’s students away, and if Master Chin doesn’t win, his school will go out of business.

Luckily Goku shows up just in time and fights as Master Chin’s replacement. Goku and Sky Dragon battle on a Lei Tai in the middle of the city in front of King Wonton’s palace, and a huge crowd surrounds the platform. Goku uses Master Chin’s “Phantom Star Fist” technique to defeat Sky Dragon’s “Cyclone Kick”, thus restoring honor to Chin’s school and settling the feud. Sky Dragon admits that Master Chin’s technique was better and decides to become his disciple.

The second example is Dragon Ball episode 131, titled “Each His Own Path.”

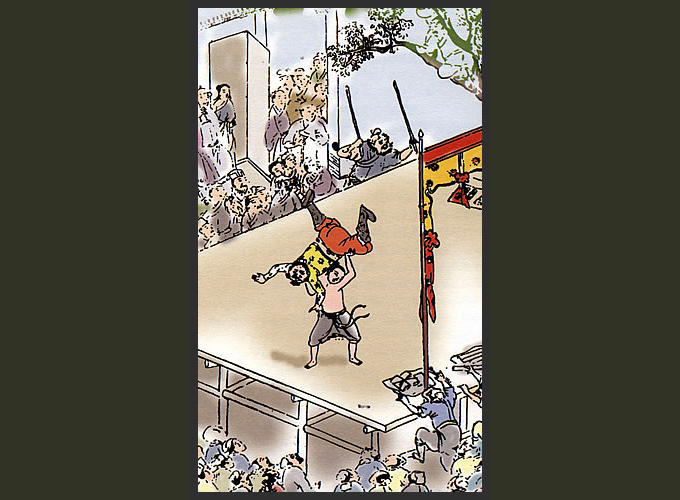

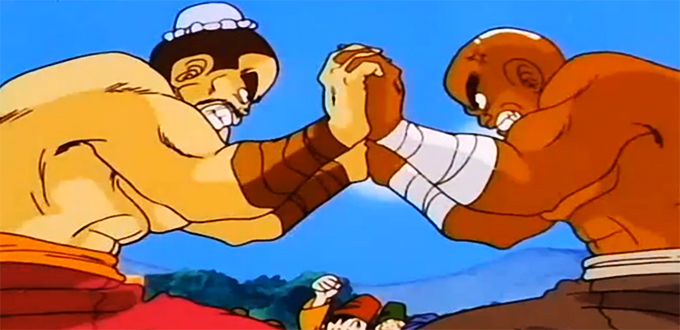

Krillin, Yamcha, Tenshinhan and Chaozu are on a martial arts training pilgrimage to the Karin Holy Land, and stop to visit a rural Chinese looking village nearby a volcano. The village is holding a festival to appease the mountain spirit and when they enter the village square they see a martial arts exhibition match on top of a circular Lei Tai fighting ring. The two competitor’s clasp hands and trade blows while the crowd cheers them on. The competitor named Tao throws his opponent out of the ring with an over the shoulder toss and is proclaimed the champion.

While joining the festivities, Krillin gets tricked into drinking some type of alcohol, as he was told it was “homemade root beer.” He drunkenly boasts to a pretty girl named Mint about how he can defeat the champion and says, “[laughter] I train every day and I’m one of the most bestest fighters in the world.” The champion Tao stands up and decides to challenge his next opponent, Tenshinhan, who accepts the challenge. But Krillin lurches up, “Hold it! Me first! Let me have a chance to take the big guy. I know I can take him; it’s what I’ve been training for. [hiccup]”

The fight begins and Krillin deftly avoids all of Tao’s punches and kicks. He rolls on the ground and begins to shake off the drunken state. Then he sees Mint and regains his composure. As Krillin stands up with confidence he bumps his rock hard head into Tao’s chin and knocks him out of the ring, becoming the new champion!

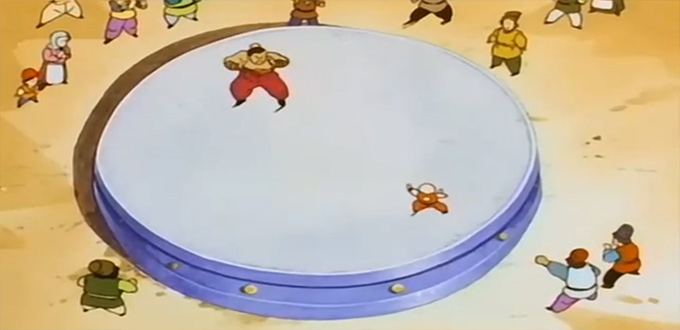

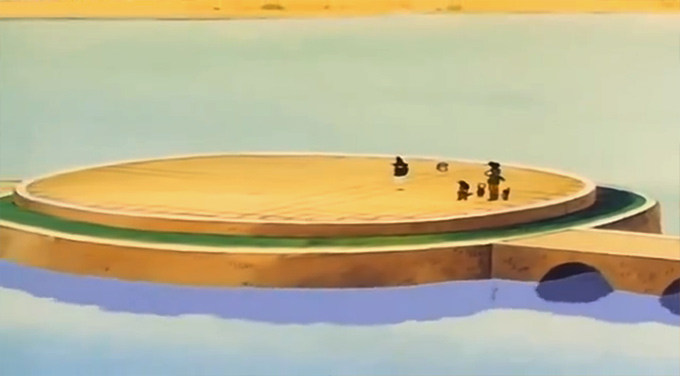

The next is during the Urunai Baba Saga, where the fighters compete against warriors from the afterlife on a circular Lei Tai surrounded by water.

The last example is in Emperor Chaozu’s tournament, in the film Dragon Ball: Mystical Adventure (1988). Fighters are competing on a large circular Lei Tai, with the winner being granted any one request by the Emperor.

The rules are announced as, “The match is decided when one of the contestants falls out of the ring, says that they give up, or is rendered unconscious.” Sound familiar?

Yamcha wins his match against a giant, red haired man, and stays on the platform until the next challenger steps up. Bora accepts the challenge. He defeats Yamcha by knocking him out of the ring and causes all of the other contestants except Goku and Krillin to run away out of fear. Of course then Tao Pai-Pai shows up and we’ve got ourselves a story, which mostly takes place on or in front of the Lei Tai. It’s also the setting for a huge battle (and resolution) between the rival Turtle School (Kame Sennin) and Crane School (Tsuru Sennin) of martial arts.

Each of these instances of Lei Tai is disctinctively Chinese or fantastical in theme and appearance. That’s because the original Dragon Ball was much more of an homage to its Chinese roots than DBZ or GT.

Lei Tai and the Tenkaichi Budokai

In this section you’ll see how the traditional Chinese Lei Tai tournament and Dragon Ball’s Tenkaichi Budokai are exactly the same.

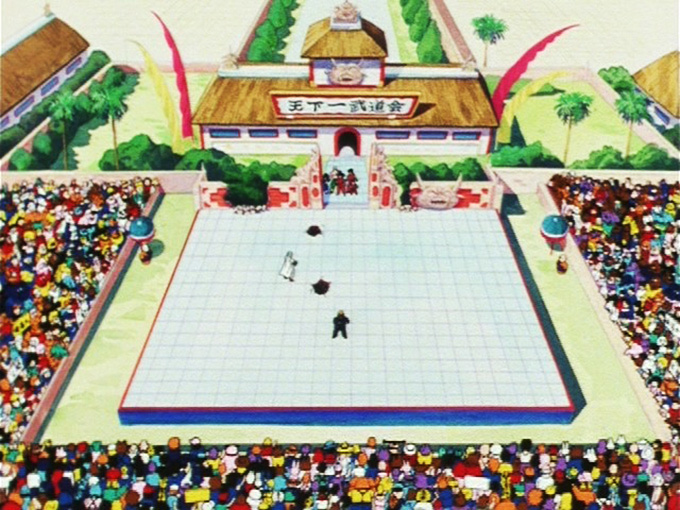

So now we’re finally at the Tenkaichi Budokai, the grand gathering of the world’s greatest martial artists. In this case it’s the 21st Tenkaichi Budokai and the first of the series.

Goku, Krillin, and Kame Sennin show up on Papaya Island, which has an appearance inspired by Toriyama’s trip to Bali.

In ancient China the styles were Shaolin versus Wu Dang, Iron Palm versus Heavy Legs, Tiger versus Crane. Masters of each style would compete to the death with techniques refined over decades of intense training. Toriyama shows us this in Dragon Ball as well. They see boxers, Kung Fu experts, Taiji masters, Bruce Lee clones, Jackie Chan look alike’s, Karate guys, big wrestlers, Sumo, and a lot of other stereotypical fighting types. They each fight in one particular style. There is no cross training in different styles with Lei Tai or in the Tenkaichi Budokai.

Before the matches on the big Lei Tai stage begin, they have to fight the preliminaries. So how do they decide the match ups?

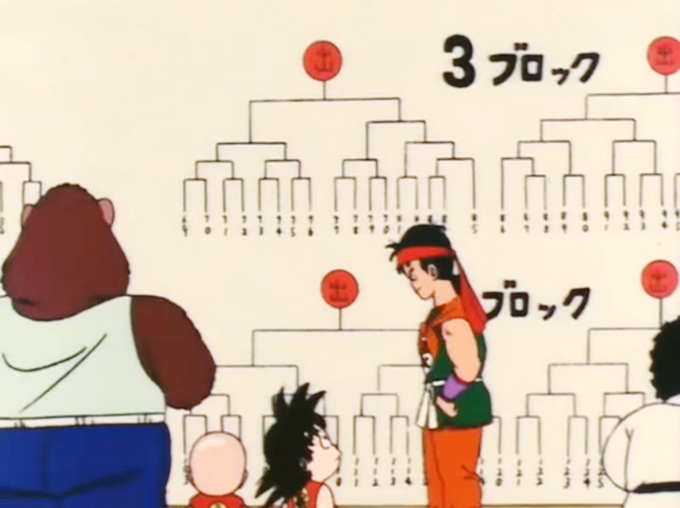

In the preliminaries they have the fighters pick a random number out of a box, their name is added to the big board, and then they get assigned to one of the Lei Tai platforms. There are 137 fighters in the Hall, and looking at the big board in episode 20 it appears there are approximately 25 people assigned per platform.

Each preliminary fight lasts for 1 minute, and if a winner has not been declared then a judge will decide the winner based on points. This is the only instance where time limits and points are ever mentioned in the series, and none if it matters because every fight ends with a knockout or ring out. The fights continue until there are 8 quarter finalists.

Goku advances, Yamcha advances, and Krillin defeats his older brothers from the Orinji martial arts temple, settling an old feud as he stands up to the bullies.

The 8 quarter finalists advance to the main Tenkaichi Budokai stage. Just as before they match off in random pairs for the quarter finals. From there they fight to determine the 4 contenders for the semi-finals, and then the final 2.

As Dragon Ball continued and more Tenkaichi Budokai’s were held, they eventually changed the pieces of paper in a box over to balls with numbers on them just like in the 1929 Lei Tai tournament, and the box changed into a rotating metal basket, similar to the copper globe.

Just as with the Lei Tai, in the 8 Tenkaichi Budokai finals there are no points, weight divisions, or protective gear. A fighter will only win based on knocking their opponent unconscious (or down for 10 seconds), knocking them out of the ring, or their purposeful forfeit. It’s extremely traditional. Simply enter the tournament and fight until you can’t fight anymore. It takes as long as it takes.

Following the rules of the Lei Tai tournament in Zhejiang, no strikes to the eyes or groin are allowed.

There is an additional rule in the Tenkaichi Budokai that says if you kill your opponent you will be disqualified. You might think this is because it’s a children’s comic so they have to keep it clean. But Dragon Ball is no stranger to death. Happens all the time. So it’s most likely the case that Toriyama was referencing the modified rules from the mid to late 20th century that made killing your opponent cause for disqualification.

Another thing that stands out is the Bu (武) Symbol at the beginning of each episode while a Tenkaichi Budokai is being held, and written on the partition that separates the fighters’ hall from the platform. This symbolically separates the Budo practitioners from the everyday people in the audience.

The Bu character appears at the beginning of each episode of a tournament until it’s complete because Akira Toriyama was paying homage to the Golden Harvest line of Kung Fu films from Hong Kong. These are the ones that influenced him to create Dragon Ball and most likely the inspiration for the Lei Tai style of Tenkaichi Budokai tournament.

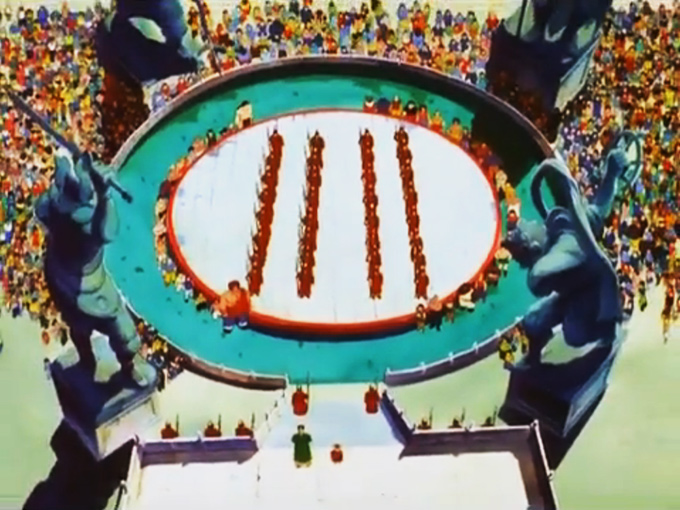

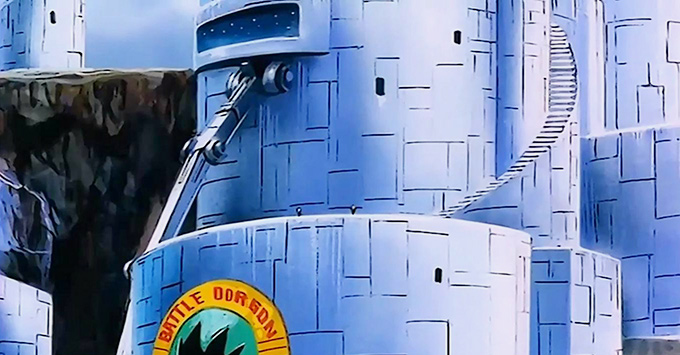

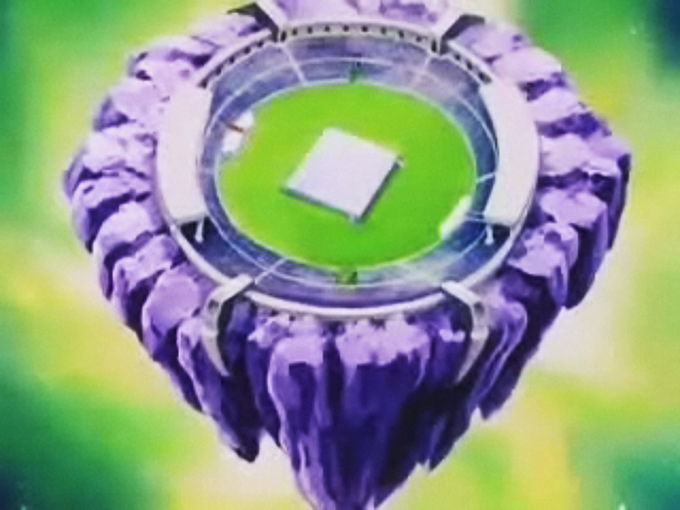

An alternative form of the Lei Tai was seen in the film Dragon Ball Z: Bojack Unbound, in the Tenkaichi Dai (Great) Budokai, where huge circular raised platforms were all set up simultaneously, hundreds of feet tall, and multiple bouts were fought at once. Opponents tossed off the platform would fall into the ocean below.

This is more or less the same scenario for each Tenkaichi Budokai, with slight modifications as the series evolved. All based on this traditional model of style versus style, no protective gear, and deadly combat.

It even appears in the Heavenly realm during the Ano-yo’ichi Budokai (あの世一武道会) in the “Other World” after Goku dies. This shows how interwoven all of these realms really are, from top to bottom, just like in traditional Chinese culture.

Historical Predecessor

The origin of the individual Lei Tai matches as seen in Dragon Ball is self-evident now that you’ve seen the comparison and learned of its history.

They’re both grand gatherings of the world’s greatest martial artists. The visual similarities are apparent, but so is the structure. Opponents are randomly assigned a number and placed in an organizational tree where they face off against opponents that use unique martial arts styles. Preliminary matches are all fought on Lei Tai platforms inside the martial arts hall. Matches begin with a drum procession and sounding of a gong. Fighters have no protective gear. The rules are the same. They fight on a large stone platform without walls that requires unique strategies to survive. The tournament is held once every 3 to 5 years. And the winner is declared “The Number One Under Heaven” and given great rewards.

It’s unlikely Toriyama came up with all of these concepts on his own. He is a manga creator well known for taking ideas from other people or places and synthesizing them together, so it only makes sense that the Tenkaichi Budokai also had an historical predecessor.

I don’t deny it’s possible that what Toriyama created coincidentally matches up exactly with how it really was in history. But it’s unlikely.

It’s also possible he actually researched ancient Chinese martial arts history to such an in-depth degree. But given his personality I doubt it.

Since Toriyama is a fan of martial arts films from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan it’s much more probable that there was some film he saw which had a Lei Tai or grand gathering of martial artists in it.

For example, the film “Lei Tai,” also called “The Big Fight” (1972) pits Chinese Gong Fu masters against the occupying Japanese forces in a death battle tournament on top of a wooden Lei Tai. They fight against Karate, Judo, Sumo and Kendo masters.

Toriyama was born in 1955 and would have been 17 when the film came out. Since he was into watching Hong Kong cinema it’s possible he saw it. He may also have been inspired by the Wong Fei Hong films which featured Lei Tai’s.

Knockout Victory

Akira Toriyama took this traditional martial arts fighting platform and exaggerated it with high flying techniques and supernormal abilities, all based on traditional martial arts concepts and real life tournaments.

The origins remained hidden even though the evidence was in plain sight. It’s simply that no one found the corollary evidence by studying ancient China (the source material for the majority of Dragon Ball’s content) and then put the pieces of the puzzle together.

After two decades of wondering where the Tenkaichi Budokai came from, we now know its origin is the Lei Tai.

To add a further layer of synchronicity, it should be noted that the Indian Kalari martial arts’ evolution into Quan Fa also carried along with it the staff and Vajra association, which was inherited by the Shaolin along with the Hanuman legend’s transformation into the Monkey King, all of which lead to Sun Wukong and Son Goku who wields a staff and subsequently fights with supernormal martial arts on the Tenkaichi Budokai platform, which is based on the Lei Tai, which is based on the Ankathattu.

So this whole thing starts 4,000 years ago in ancient India, then proceeds to China and finally into Japan, where thanks to Akira Toriyama it goes all the way back to China and ancient Indian martial arts which were believed to have been divinely derived from Vishnu and the deities that were able to strike down their foes like lightning.

As we witness in the Tenkaichi Budokai there are cataclysmic fights that rock the stadium with sonic booms, concussive blasts of light, huge explosions, warriors that move so fast they cannot be seen, magical flight into the clouds, and near 10 count conclusions that leave the audience reeling.

When lightning emanates from their bodies as if gods are on the stage, the Tenkaichi Budokai becomes the modern artistic manifestation of a “striking thunder hand platform.”

Resources

1929 Hangzhou Lei Tai Tournament

Pro Kuo Shu UK – Lei Tai Warriors

' . $comment->comment_content . '

'; } } else { echo 'No comments found.'; }