Nathan Johnson Makes Waves on DBZ

Are you ready for the definitive, ultimate uncut interview with Nathan Johnson, brought to you in pristine High-Definition 16:9 with fully restored dialogue?!

As a Dragon Ball fan you are most likely familiar with Bruce Faulconer (Faulconer Productions) and Mark Menza, who composed for Dragon Ball Z and Dragon Ball GT, respectively.

But you may not be as familiar with Nathan Johnson, the composer responsible for Dragon Ball Z: The Ultimate Uncut Editions [aff] in 2005, which are episodes 1 to 67, and Dragon Ball Z movies 2, 3, 10, 12 and 13.

Why is that? Who is Nathan Johnson and how did he end up working on these DBZ projects?

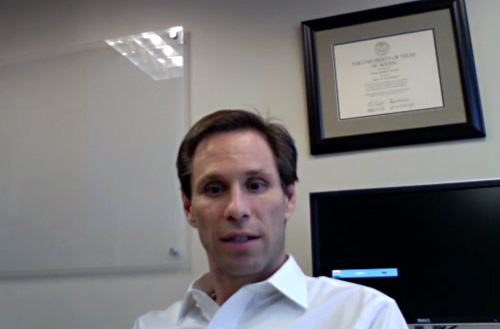

Nathan has never been interviewed before and was gracious enough to be a guest on The Dao of Dragon Ball.

Now for the first time ever you will get to hear Nathan’s story of how he helped create the #1 action anime series of all time.

For the Love of Music

Derek: Welcome, Nathan, to The Dao of Dragon Ball.

Nathan: Flattered.

Derek: Nathan, thank you very much for taking the time to speak with me, I know you’re very busy. I really want to find out the inside story of composing for Dragon Ball Z.

Your professional background has little to do with entertainment. Before you got the job composing on Dragon Ball Z, you were in business litigation law. You graduated from the University of Arizona in 1990 with a degree in Physics and from the University of Texas School of Law in 1993.

Can you tell me about that? Why would a practicing business lawyer suddenly switch over to creating Japanese entertainment?

Nathan: I played music throughout my childhood, usually not as well as I should have. Always wrote music and enjoyed it, but it was always bad and I knew it was always bad. I didn’t really consider music as something a person could have as a profession. I was pretty ignorant in that respect. But I couldn’t shake the bug.

My road to writing music for Dragon Ball Z started in law school. I went to the University of Texas in Austin and the law school was right next to the music building, which had several floors of Steinways and practice rooms.

I then got out of law school and became a lawyer and continued to play and write. I shared it with a professor at a local university and he said, “Gosh, this stuff is pretty good.” I thought it was still terrible. I found a world renown symphonic and opera composer in town who heard my music and confirmed it was quite bad, but said that I might have something to offer if I really worked hard at it.

So for the next several years while I was a lawyer I essentially went to school without going to school, and really learned to how to write music with Robert Xavier Rodriguez. He was a classical symphonic composer, and I was doodling around with the blues and things like that.

Derek: What did you do next?

Nathan: I eventually quit my job as a lawyer and lived off my wife’s income for a while because I wanted to make a real go at this. I figured other people who really tried writing music spent all their time doing it, not half their time while trying to be a lawyer. I wrote classical music for a while and at some point decided I want to make a living.

I studied opera composing and got the chance to study with a famous opera composer, Carlisle Floyd, who decided I wasn’t very good at writing for opera, but that writing for theater or stage was something I could do.

I launched into the world of film and television composition. It was a long, difficult road starting from nowhere. I did a little film, made almost no money, and worked very hard at putting together demos where I ripped music off of and re-scored TV commercials, trying to find jobs. A local shop here saw my stuff and said, “Hey, this is pretty good!” and the pay [for a gig with them] was good, but my career was still going nowhere.

A Twist of Fate

I was trying to open up my own law office because if my contract law gigs weren’t paying enough, then I needed to have my own office.

A place near my house was for rent. I called the number on the sign out front to rent an office, and the guy on the phone said, “What will you use it for?” I said “To practice law, but to be honest I might throw an electric keyboard in there and make some musical noise, but nothing to disturb the other tenants.” He said, “What kind of music?”

Derek: Get out of here!

[Note that the Cocanaugher’s are co-founders and executives of FUNimation.]

Nathan: Yeah, haha, he owned that building. Robert said, “Do you have a website with any music on it?” I said, “Yeah, but I’m not a composer anymore.” So I gave him a link to this awful website that I had built in a word processor. Haha.

Apparently Robert ended up going to the website and listening. Then he walked into Barry Watson’s office and said, “I think I’ve found that composer you’re looking for.”

Derek: Wow.

Nathan: He called me back about an hour later and said “We’d like to meet with you tomorrow.” I went and they offered me the job. That was a Friday, he said, “You’ve got to tell me by Monday.”

Derek: That’s amazing.

Nathan: He gave me a bunch of DVD’s of Dragon Ball GT because that’s what was sitting around in his office. I looked at it, and, well, I had a classical world music background. These rock tunes, I knew how to do that, but wasn’t sure if I could. I went in and asked Barry, “What do you have in mind?” He said, “We’re going to release this Dragon Ball Z Uncut and I want to take it to a new place. I want it to have an orchestral element of sound, something a little more cinematic.” I said, “Okay, I’ll take the job.”

Derek: So there was no…

Nathan:

After the interview they thought for some reason I could handle it. They also figured they could fire me as I was their first in-house composer, with all the benefits and drawbacks of that kind of arrangement.

Derek: Haha, I’d love to hear about those. But that’s extremely fascinating, Nathan. I am astounded that there was no audition process and that you were at a place in life where you were like, “I’m done with this and don’t even want to compose music anymore.” And you just happened to go to the building that was owned by the guy who is connected to FUNimation and Dragon Ball Z, and I guess he liked your style and wanted to give you the job.

Nathan: It was one of the most bizarre collisions of circumstance I’ve ever experienced. The building wasn’t even in Fort Worth or Northwood Hills where there offices were. It was out in Dallas. But it was about a mile from my house.

Derek: That’s unreal and very fascinating.

Starting the Job

Derek: So you didn’t know anything about Dragon Ball Z and you had never seen it. What did they tell you when you told them that you wanted to do the job? What was the next step?

Nathan: They wanted to know what I thought I would need. I had to be honest with them that I did not have the resources that Bruce Faulconer or Mark Menza had in terms of production.

Interestingly enough, Dragon Ball Z Uncut wasn’t yet up on the block at that time. They were rescheduling things. I originally thought we would start on that, but they said “Actually no we’re going to work on this other show called Case Closed.” We worked on Case Closed for a couple episodes and then they decided they didn’t want original music. I don’t think they didn’t like my score, because we did this really cool theme music for it.

There was another show that we did a couple episodes for that also they decided not to use music on. By the time we came up with musical concepts and did a pilot of each of those shows, DBZ was up and ready. Barry said “Never mind those. Let’s get to work on this, this is my real deal anyway.” Then he explained to me that these are the episodes that weren’t done before and they wanted to do something new with it. Barry and I and another guy from FUNimation, Matt Cheney, worked with me on these.

We sat down to work for a quite number of hours for a week or two, to try to come up with the sound for the show before we really started scoring. When we thought we generally had an idea Barry turned us loose and got to work.

http://youtu.be/yZN0RwR7eg0

Matt and I worked well together on certain things and not on others. Ultimately FUNimation found things that they thought he would very well that didn’t involve Dragon Ball Z. So now it was on me to do everything, which artistically we rarely like to simply… it’s hard to collaborate straight out of the box. It kind of turned me free because Matt and I had very different styles. It turned me free to follow my style, but frankly I was a little green, so my style wasn’t all that firm either. Down the road I collaborated with some people who were completely different from me and it was great because I had found my voice.

One of the most fun things I did on a Dragon Ball Z project was to collaborate with Dave Moran, the heavy death metal guy, on one of the movies. He was death metal and I was electro orchestral, and it was a blast. That score for Fusion Reborn had a really strong fan response.

Mixing Things Up

Derek: So you started with a partner and that didn’t work out, or FUNimation just decided, “Let’s split these guys up?”

Nathan: Yeah, Matt and I didn’t work well together on that show. But they did bring me a guy who I had a great time working with later. A mixing engineer named Neal Malley, in Dallas. Neal’s job was to go through what I did on a particular score for a few episodes and mix it. But his other job was to look for stuff that worked particularly well for a chase sequence, fight sequence, or humor or suspense. He would harvest it and create a categorization. Remember, this was wall to wall music, it was very hard to fill every second, but that’s how they wanted to do it.

Derek: Right. Barry Watson did the same with the rest of Z and GT as well. He told Mark Menza “We need constant sound.”

Nathan: Constant sound. We composers always want to take a breath [though]. Oh, and by the way, [they’d say] “Turn the volume up.” Haha. “Make this louder and constant.” But that was the job.

In the commercial business you don’t have 8 weeks to sit around thinking about your episode. In fact some weeks you had to knock out 2 episodes a week, which is a PHENOMENAL weight. I was really struggling in the early episodes to find my voice and get a handle on the show. Some of it didn’t work so well.

There are other passages that work really, really well, and Neal would go and harvest those. He would find another episode where the music could be placed intelligently. Either it would stay there as is or he’d say, “Hey Nathan, I like the thing you did here but to work in this episode it needs to be modified.” I would take the sequence from my software and line it up there and figure out how to rework it into that episode.

That may sound like a cop out but it’s not really a cop out. The highest level scoring in films you’ll find they use the same material over and over again because it lends continuity. It was a necessity.

After about 20 episodes I hit a stride. We had enough material to fill up chunks of entire episodes, and that would allow me to concentrate on the areas that didn’t work with the library of stock that Neil had built. Or the scene particularly appealed to me and I could get excited about it and write something new and good. I think some of my favorite moments of the episodes were from those times.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4-CeMa25ACc

Derek: So it was very much a collaborative effort between you the composer and Neal the mixing engineer, is that right?

Nathan: Absolutely.

Derek: A lot of people don’t know that. They think the composer makes the music and puts it in the show and what you hear is all his responsibility.

Nathan: No, and not only did Neal help me fill space, sometimes what comes out of the composers box, however brilliant it might be conceptually, it doesn’t sound that good. A good mixing engineer can take that and turn it into what it really is, what it really wants to be. He adds in panning and that sort of thing. Neal would have fun panning things around the room and adding all kinds of whiplash. We had a good time and did some good work together.

Understanding Dragon Ball

Derek: Was the original contract that you got hired for only for the episodes 1 to 67, or was the possibility out there that you would continue onto the remaining episodes? If you were given the chance, would you have continued with the rest of DBZ?

Nathan: I think the contract said absolutely nothing about how many episodes I would score. But I think the intention was to only do those 67. I also think somebody was kicking around the possibility of rescoring the other episodes also, but I think that was only at the back of somebody’s mind, and it was never presented to me.

Derek: So when you got the job you didn’t know anything about Dragon Ball Z. How was it described to you? What was your perception of the series? 67 episodes is a lot of work to do when you don’t know anything about what it is you’re supposed to work on.

Nathan: Dragon Ball Z was completely foreign to me, and not foreign in a national or geographic sense. I didn’t understand it. It took me a while to start to relate to.

I probably should have talked to the fans early on, because I struggled to relate. So I had to start looking. With time I did start to understand what this show is about. It’s not like any other kind of show. I got a feel for it and to understand the characters, the themes, the fans. Not incidentally the composing got a lot easier after that.

DBZ wasn’t explained to me. I had to figure it out. While I was figuring it out it was much harder to write than afterward.

Derek: It was the same thing with the voice actors. As they became more familiar with the characters and story their voices changed and evolved. As time went on they got more into it and the performances improved.

Nathan: Probably the same for me, I hope.

Finding the Voice

Derek: If I were to describe the sound of your compositions for DBZ I’d say it is cinematic, with a high paced sense of thriller and action oriented science fiction undertones. How would you describe it?

Nathan: I think you did a very good job of describing it. I can’t improve on that. I might distinguish a little between the episodes and the movies. I certainly had more time to go for a cinematic sound for the movies, although I never wanted to sound like Hollywood. It wasn’t natural for me and not what I was trying to do. The episodes I think were a little more electro orchestral, but I think you described the sound I was trying for really well.

Derek: What were your musical influences when creating the DBZ soundtrack? You mentioned the heavy metal tones in there; were there also film influences such as from Aliens, Tim Burton films, or possibly video game music, like the Metroid series?

Nathan: Tim Burton films definitely had an influence. I was even listening to Pee-Wee Herman’s Big Adventure. There’s a lot of silliness in Dragon Ball Z. I had never scored silliness before. Then there’s some creepy stuff. Batman was in there. Certainly some John Williams for inspiration. Sometimes I would just listen to basic pop music for ideas.

Neal and I declared that we needed a movie day, we never told Barry this, haha, and we went and watched one of the Star Wars episodes, just to immerse ourselves… at some point you get tired artistically, and it helps to see a master at work. The two of us went and got some popcorn and watched Star Wars and came back and did some really good work together.

Derek: That’s good to hear. Had you listened to any of the existing Dragon Ball music before starting production? Namely, the Japanese Dragon Ball Z soundtrack or Faulconer Production’s Dragon Ball Z soundtrack?

Nathan: I didn’t have access to any of the Japanese music. I did listen to some of the Faulconer music and I had met Bruce before this and Bruce was very nice to me. He helped me out. I was trying to make a demo and he gave me $300 or $400 of work to get my demo ready and only charged me $50.

Obviously it must have worked because he did over 200 episodes and the world loved it. So I had to find a way to figure out what he did right and not to do the same music, but somehow capture the spirit of the characters and the show. I studied each episode to see how Bruce treated certain scenes and then I got away from it, put it in a box, and worked to create my own sound.

My sound was very different from Bruce’s. He was a professional and great at what he does, but if I was not going to be a lawyer and make music for a show I didn’t know anything about, I had to do it in my own voice.

Derek: Like you mentioned, your styles are totally different.

Nathan: For that show, yes. I picked up on something Mark Menza said in your interview with him. You were talking about “Why did you do it this way?” and so on. Mark’s response was, “The producer asked me to.” I don’t even know what Faulconer’s style is, I just know how he scored Dragon Ball Z, and it wasn’t how I wanted to do it.

Derek: You mentioned Bruce was kind to you when you started. There are all kinds of rumors out there about why Bruce wasn’t scoring the first 67, things like that. The rumor is that there was some sort of conflict between the two of you, was that the case?

Nathan: I’m almost certain it wasn’t. I believe the rift was between FUNimation and Faulconer, and I don’t know anything about it.

It was only after I had the job that someone brought up Bruce Faulconer. “Oh, okay. Well, why isn’t Bruce doing it anymore? ” “We don’t want to use him anymore, we want to use you.” “Okay!” Back to work.

Making the Music

Derek:What was the music development process like? Was it all synthesized or did you play live instruments? What was the supervision from Barry Watson or FUNimation producers?

Nathan: Barry was very involved for the first 2 episodes. We worked pretty hard to try and establish a sound. I remember one day Barry kind of came out at 2 o’clock and we were going to work till 4 when Barry would go back home. About 5 o’clock came around and Barry was still there, we were working on one scary scene.

It gets to 5:30 and my wife was working late. I had 2 kids at the time and I had a 1 year old in daycare, literally a quarter mile away. I said, “Barry I know we’re making great progress but I’ve got to pick my kid up.” Barry said, “I don’t mind. I’ll wait.” I drove across the street, picked up my 1 year old, came back and put him on my knee, and started scoring the enemy spaceship.

Derek: Haha.

Nathan: I tell that story just to say we were working closely, in a groove, the 1 year old thought it was really cool.

Derek: That’s a good litmus test.

Nathan: Yeah, the 1 year old continued to be a good litmus test later on. For the first two episodes Barry had opinions about every element of the show, this works, this doesn’t. But by episode 3 he wasn’t looking at them with me anymore, he would call in. Probably by episode 5 I was loose and running. I don’t think I heard anything objective after episode 4 or 5.

Derek: So once a week you’d score an episode, maybe 2, and you would go into their studio to do that, or the office you had rented?

Nathan: The little Coconaugher building I ended up not renting. They hired me as an employee and that became the “FUNimation East,” I guess we would call it. It consisted of Neal and I, and they set up a recording booth over there so a couple times a week some engineers and actors would work in the booth down the hall. So no, I wasn’t in the FUNimation building. I was isolated.

Derek: Okay, I see. Can you tell me a bit more about the films? What was the difference between working on the episodes and working on the films? You had mentioned Fusion Reborn earlier. Can you go into more detail?

Nathan: Yeah, I think I worked on 2 films while I was still officially an employee of FUNimation. FUNimation was later purchased by Navarre. I think one of them was with Dave Moran, maybe that was Fusion Reborn. The film was fun because I got more time to do it. Dave and I worked very well together and it was fun.

We had this heavy metal orchestral sound. Dave would come in with 5 or 6 minutes of ripping guitar things. I would say, “This didn’t work here but I think it’s a good idea.” So I would take Dave’s guitar, chop it up, put some orchestra under it and then bring it back to him. He’d say, “Yeah, I can do that!” and he’d add some more guitar where it was needed. That was the most fun I had on the project.

Anyway, that was only one movie. For several of the other movies I was a freelancer at that point, because when Navarre bought FUNimation they had no interest in having an in-house composer anymore. I wasn’t part of management but I guess they wanted to cut costs and weren’t really interested in doing original music on a lot of things. So they turned me loose all of a sudden.

Barry wasn’t happy about it. Much against his protest he drove out and told me I was fired, I’m sorry laid off, haha. He immediately needed me to do some films, which was great because I could charge much more money as a freelancer. Films turned out to be more fun because I got more time and was paid better.

You asked if it was all computer or were there some acoustic instruments? Mostly straight out of the computer. A little bit of help from a guitar.

I remember I wrote it into the theme and it sounded awful because I didn’t have an engineer with me or a recording studio. I ended up laying a sampled ocarina on top of the real ocarina, and it created a very interesting sound.

Derek: That’s cool, those stories are interesting where you get creative to make it work, and it does.

Taking it to the Next Level

Well that’s eye opening, isn’t it?!

Nathan was hand picked to be the composer on Dragon Ball Z: The Ultimate Uncut Edition. No auditions, no familiarity with the series, no professional equipment, and little experience with the medium, yet he was the one FUNimation chose.

Why? Because Robert and Barry heard something they liked, and it’s my guess that they also saw Nathan’s raw talent and potential.

Nathan was about to close his doors to music forever, but as soon as he let go of that pursuit he was provided with the opportunity of a lifetime. Nathan did his absolute best to make it work and have fun while doing it!

How were Nathan’s compositions received by the fans? And does he have more revealing stories to share? Check out Part 2 of my interview with Nathan Johnson.