The Cloud-Soul in Dragon Ball

Discover the cloud-soul in Dragon Ball! What is the cloud-soul? What is its purpose? How is it portrayed? And where did Toriyama receive his inspiration?

The Religious Soul of Dragon Ball

This article began as an attempt to explain the traditional and modern ways that the soul is portrayed in Dragon Ball.

According to my own analysis there are 7 real-life religions that inspired Dragon Ball. Each of them has their own beliefs about life, death, the afterlife, and the soul.

These 7 religions are Buddhism, Dàoism, Shintō, Hinduism, Christianity, Islam, and Satanism and Witchcraft. Plus the two additional philosophies of Confucianism and Egyptian polytheism.

I now have enough content to discuss about religions in Dragon Ball that it could be its own book.

That’s why in this article we will focus on a single aspect of the soul in Dragon Ball: The cloud-soul.

We’ll start by showing an example of a cloud-soul in the series, and then defining it.

Dragon Ball’s Cloud-Soul

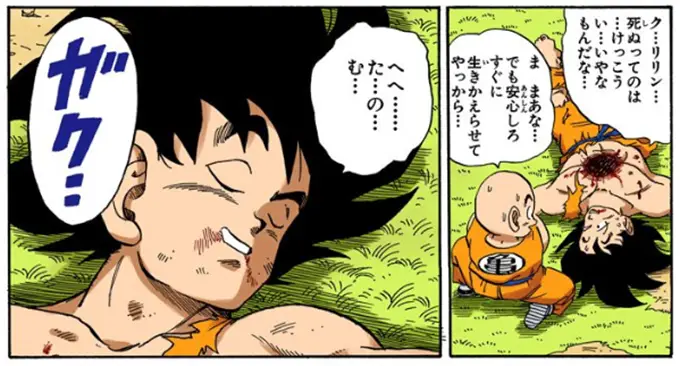

The first example of a cloud-soul appearing in Dragon Ball occurs during the Saiyan arc, after Goku dies while fighting his brother Raditz, at the hands of Piccolo.

Goku holds Krillin’s hand, dies with a peaceful smile on his face, and a moment later his body vanishes.

Toriyama then takes Goku to the Other World for the first time.

Shintō is the native religion of Japan. The a-no-yo (あの世, the “Other World,” or “afterlife”) is the Shintō concept of another dimension in which spirits, called kami (神, “god,” or “spirit”), and the animus of the deceased, live on in another world. Its counterpart is called ko-no-yo (この世, “This World”), where the living exist.

According to Shintō beliefs there is a thin and permeable line between This World and Other World, and beings with the ability to traverse these realms can do so whenever they like.

In this case, Toriyama’s depiction of the Other World in Shintō is actually a combination of Buddhist, Dàoist, Shintō, and Christian ideas.

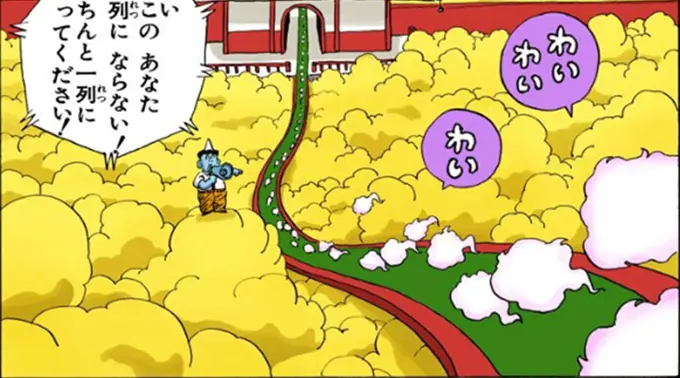

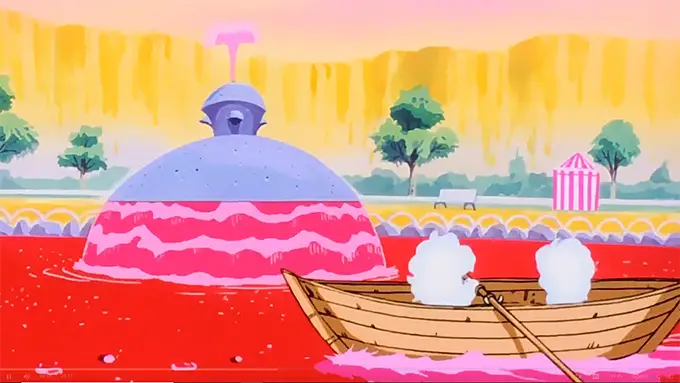

At the top of the image we are shown a large Chinese palace that is floating atop the clouds. The gabled roofs have ox horns protruding from their tops. This is because of the horns reflect the palace’s owner, whom I’ll describe soon.

The official name for this building in the Dragon Ball guidebooks is the Welcome Center. As such, a large sign in front of the palace reads, “WELLCOME.”

You might be thinking, ‘Wait. That’s not spelled right. And the other image above only had one ‘L,’ so what gives?’

The original image drawn by Toriyama said “WELLCOME,” with two ‘L’s.’ So this was likely a spelling mistake by Toriyama who did not realize that when the English words of ‘well’ and ‘come’ are combined, that one ‘l’ is dropped and the words are conjoined, as ‘welcome.’ In later editions of the manga and anime the publishers corrected this mistake by removing one of the ‘L’s’, which lends credence to this theory that it was a mistake.

What we are most concerned with in this image is a stone walkway leading toward the palace and under the sign.

This walkway has a line of clouds floating above it.

These clouds are cloud-souls.

The cloud-souls are talking amongst themselves with the Japanese onomatopoeia of wai-wai (わいわい, “lively chatter”). This shows us that even though they have no mouths, they can still talk. In the anime they make high-pitched and cute little sounds of verbalized expression that sound similar to words. In the English dub they’re actual words, while it’s unclear in the original Japanese.

Standing on the clouds next to the walkway is an oni (鬼, ‘oh-nee,’ “ogre,” “demon,” or “spirit”).

Oni are beings who are born in the afterlife and assist the bureaucracy of the dead.

Oni are a Japanese monster and synthesis of several Asian monsters from India and China that play a common role in the Buddhist afterlife as enforcers of punishment. Their job is to lead the souls to the afterlife, and once there, to enact deliverance or punishment upon each one. In Japan they are considered a type of yōkai (妖怪, “specters,” “ghosts,” or “phantoms”).

This oni is wearing a Western office shirt and tie, office shoes, and a tiger-skin patterned pair of pants. This is because the tiger-skin loincloth is a traditional outfit for spiritual beings in Buddhism to indicate spiritual power. Toriyama often combines the modern and traditional like this, in a way that appears seamless.

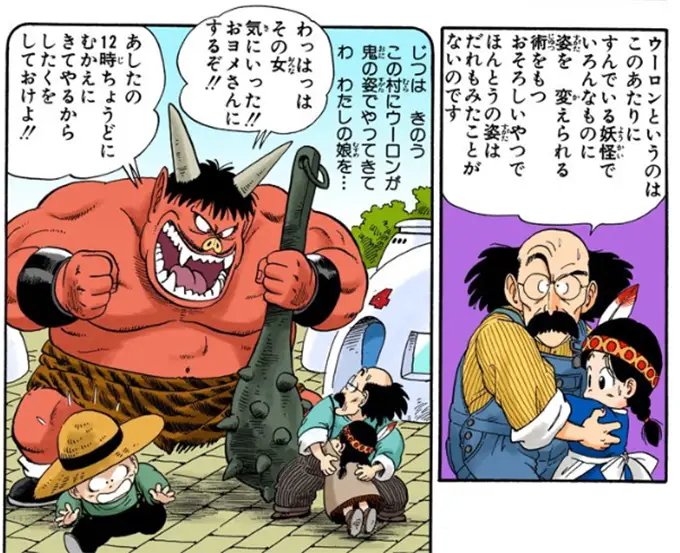

Toriyama showed us a depiction of a classical oni in Dragon Ball chapter 5. Here we see a flashback of Oolong terrorizing a village in order to kidnap beautiful girls. He transforms into an oni to frighten the villagers into submission. This scene is inspired by the pig-man character of Zhū Bājiè in Journey to the West who does the same thing.

Oni usually carry a large kanabō (金棒, “iron club”) that they use to smash people into obedience. You can see Oolong carrying such a weapon in the image above. But this oni in the Other World is speaking into a modern Western megaphone and instructing the cloud-souls on what to do. He says, “Yes, that’s right. You there. Two lines is not allowed! Please neatly form one line, thank you very much!”

If I recall correctly from watching the English dub 20 years ago, they translated this as, “Please proceed forward. Hey, you there! Single-file! Get back in line!”

Journey to the West scholar Jim McClanahan notes on his website that two such spiritual beings lead Sūn Wùkōng to the afterlife in chapter 3 of Journey to the West.

In classical East Asian stories of such beings, they individually lead each dead soul to the afterlife. But one might question how there could be enough beings to lead the millions of people that die every day in the world, or even billions across the universe, to the gates of the afterlife.

In Toriyama’s rendition we see that the dead just appear on the walkway the moment after death. Naturally they would be confused by their newfound environment and lack of body, so it makes more sense that a single oni would be there with a megaphone telling them what to do.

With that part covered, let’s dive into what a cloud-soul is and where it comes from.

Cloud-Souls in Dàoism

The idea of cloud-souls comes from Dàoism, the native religion of China.

Dàoists believe that human beings have two types of souls.

The first soul is called the hún (魂, pronounced ‘hoon,’ “cloud-soul”). The hún provides a being’s personality and consciousness. These are the voluntary active, waking, and deliberate thoughts and actions of a person. For example, movements, speech, and cognition.

The second soul is called the pò (魄, “white soul”). The pò provides a being’s subconscious. These are the involuntary, vegetative processes of the body that occur without deliberate thought or action. For example, growth of the body, healing, excretion, and inspiration.

Together they are called húnpò (魂魄, “soul,” or “dual souls”).

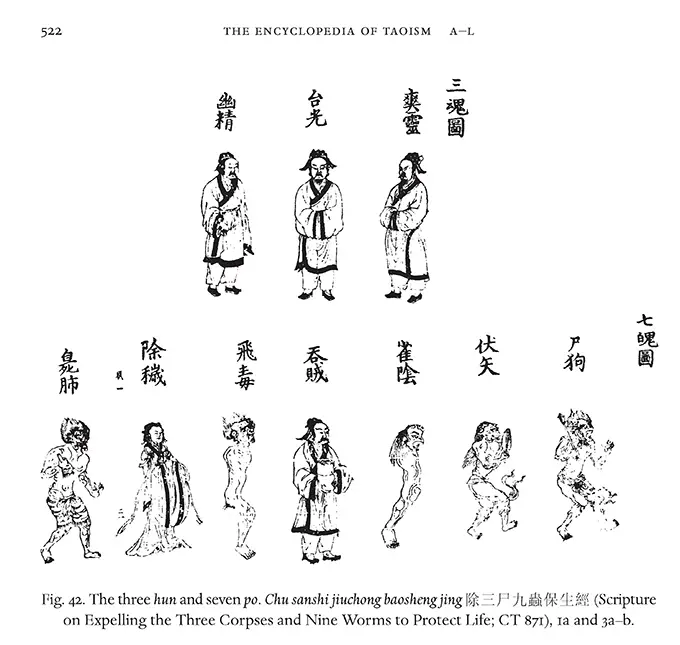

Three hún and seven pò – Encyclopedia of Taoism

Originally there were just these two souls, but by the time of the Hàn Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) there were actually 10 counts of these two souls in the body. They were defined as the sānhún qīpò (三魂七魄, “three hún and seven pò”). Toriyama doesn’t go this far with his depiction, instead sticking to the original two.

“Cloud-soul” is an English translation of hún (魂) because hún consists of two parts. On the left is a stylized radical for yún (云, “cloud”). On the right is the hànzì of guǐ (鬼), which you may recognize as the Japanese kanji used for oni (“ogre,” “demon,” or “spirit”). In this case when you combine the two together you get “cloud” and “soul.” Thus, “cloud-soul.”

The term of cloud-soul became popular in China through its use in the Dàoist scripture called Dùrén-jīng (度人經, “Scripture on Saving Humanity,” ~400 A.D.). It became the defacto scripture of the Língbǎo (靈寶, “Numinous Treasure”) sect of Dàoism and reached its zenith in the 6th century A.D. during the Táng Dynasty.

According to the Dùrén-jīng, upon death, the hún leaves the body and travels to the afterlife, while the pò stays attached to the body and returns to the earth. In other words, the húnqì (魂氣, “cloud-soul energy,” or “breath-soul”) ascends, while the xíngpò (形魄, “form soul,” or “bodily soul”) descends.

The hún then becomes a shén (神, “god,” “spirit,” or “supernatural being”). It remains in the afterlife and has the spiritual power to protect its descendants and be prayed to by them. When the pò descends to the earth, it dissolves along with the body, unless it is angry, at which point it becomes a guǐ (鬼).

This dualistic nature of mankind’s soul is fundamental to the understanding of Chinese spirituality. It goes along with Dàoist yīnyáng (陰陽, “negative and positive,” or “black and white”) concepts. Hún is associated with yáng and clouds, while pò is associated with yīn and the moon.

There’s more I can say about the etymology of cloud-soul, but I’ll save that for a Dragon Ball Z Culture book. But regarding their name in Japanese, I’ll say that from what I can tell these clouds are never given a name in Dragon Ball, nor in the official guidebooks.

However, the literal translation of hún into Japanese is tamashī (魂, ‘tahmah-shee,’ “soul,” or “spirit”). So for lack of a proper Japanese name, these cloud-souls are called tamashī.

In theory, the dualistic souls in one person would then be called konpaku (魂魄, “soul,” or “anima”) in Japanese.

The White-Soul in Dragon Ball

The second type of soul according to Dàoism is the pò (魄, “white soul”).

We never get to see the pò portrayed in Dragon Ball in a direct manner, but it still plays a role in Dragon Ball in three ways.

The first example of the pò in Dragon Ball is the ghosts that inhabit Uranai Baba’s palace. According to Dàoism, a ghost is created when a person’s pò becomes angry and instead of staying with the body after death, begins to haunt people and attack others in the world of the living. Which is to say, a pò becomes a guǐ (鬼).

The most noteworthy ghost in Dragon Ball is Obake, the personal assistant to Uranai Baba, who welcomes guests to her palace. This palace has an Egyptian polytheistic architecture and is located on a lake in the middle of the desert. I argue in Dragon Ball Culture Volume 4 that Baba’s palace is a symbol of spirituality in a realm of emptiness and void.

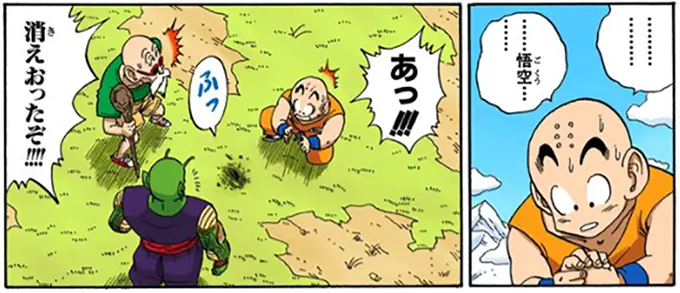

The second example of the pò in Dragon Ball is in the original Dragon Ball when Krillin, Rōshi, and Chaozu are killed by Piccolo Daima-ō and his demonic spawn. Goku tells his friends not to burn their bodies—as would be customary in Buddhism—because in order to wish them back to life, Shenron needs to have a vessel for their souls to inhabit.

This could be interpreted to mean that their hún has traveled to another dimension, and if Shenron were to create a new body for them, that it would not have the same characteristics as their current body, which is still inhabited by their pò.

There is a similar story in Dàoism regarding the immortal Lǐ Tiěguǎi (李鐵拐, “Iron Crutch Li”). Lǐ goes to visit Lǎozi by sending his spirit to another realm, and his disciple is charged with watching over his body while he’s gone. But the disciple gets called away, yet his master hasn’t returned, so he burns the master’s body before leaving. Then when Lǐ returns he has no body to inhabit, so he is forced to take over the corpse of a recently deceased and crippled beggar. Even though his hún is immortal and has divine powers, his original pò has been burned, while his new pò is crippled. As a result, he walks with an iron crutch in all future depictions.

However, this idea gets retconned in the Dragon Ball Z portion of the series when Shenron recreates people’s bodies out of nothing. For example, Chaozu makes his own body explode when fighting Nappa, yet is then revived with a new body. Same for Krillin after Freeza explodes his body with his mind. Shenron also restores Tenshinhan’s severed arm, showing he can restore individual body parts. In all cases their original body before death is revived.

The third example of the pò in Dragon Ball is when somebody gets to keep their body in the afterlife or needs a vessel to contain their body when they visit Earth. This first occurs when Son Gohan returns to earth for a single day in order to visit Goku at Uranai Baba’s palace. He returns in his original body at the time of death, even though he has been deceased for years. His body works so well that he can perform martial arts and fight in Baba’s tournament.

This idea is inspired by the Japanese Obon (お盆, “the Buddhist festival for dead ancestors”), where the dead come back to the world of the living for one day. It’s derived from the Chinese Yúlán-pén (盂兰盆, “Hungry Ghost Festival”) and is overseen by the lord of the underworld named Enma-dai-ō, whom we will meet in Dragon Ball in a moment.

But the most well-known example of this type of pò depiction is when Goku dies and gets to keep his body in order to train with King Kai in the afterlife. Afterward, this also occurs for other spiritual warriors. In this case the hún and pò travel together to the Other World.

When Toriyama depicts a warrior who gets to keep his body, he draws a halo over their head.

A halo is a flat disc that hangs above or behind a person’s head to indicate that they are holy or spiritual. Halos can be found in Buddhist art, but are most often associated with Christian iconography and Western spirituality.

This is how Toriyama conveys that dead people from a-no-yo are present in this dimension with their mortal bodies, or that people who keep their body in the a-no-yo have their bodies intact. This makes it easy for the reader to understand that Son Gohan and Son Goku have passed away and yet remain alive.

McClanahan feels these spiritual warriors keeping their bodies in the afterlife and continuing to train is similar to the Norse belief in Valhalla. Here, Vikings keep their bodies and fight an eternity of glorious battles.

My personal take on it is that it’s similar to the paradises of a Buddhā where spiritual cultivators are given an immortal Buddhā Body created by the Buddhā of that realm and allowed to continue cultivating to higher realms. This is done when a cultivator has transcended the Three Realms and has thus escaped the cycle of life and death, yet has fallen short in their character in a small regard that prevents them from attaining Arhatship, Bodhisatvahood, or Buddhahood. The Buddhā thus gives them a new body to allow them to continue their cultivation.

It also occurs in the case where the cultivator has succeeded in cultivating their body to have gone beyond the Five Phases and thus become immortal to old age, yet are then mortally wounded. In such a case their hún ascends to that Buddhā’s realm with their pò and immortal body, and they are allowed to continue cultivating their hún to reach a higher standard.

With this said, it could be equally argued that Toriyama is not as concerned with the pò as he is the hún. This is why he illustrates the hún, but not the pò, and leaves what I described to your interpretation.

Gathering of Souls

Returning to the scene at this Chinese palace, we can determine that these are the cloud-souls of people who have recently died within the Dragon World. Each cloud represents one person. The reason they are just clouds, and do not have their body, is because the hún ascends while the pò descends.

We don’t know anything about these people, nor where they come from. In fact, they may not even be from Earth, as we learn later in the series that all beings who die in this universe travel to this palace. They could have come from anywhere in the universe where there is a planet that has mortal life.

This follows Dàoist thinking, in that all beings who pass away travel to the Palace of the Southern Pole Star. Regardless of where they died, that’s where they go.

In ancient Dàoism, they didn’t even have a palace, it was just a dark underworld. So this idea is one that evolved over time. I’ve seen other sects say that it’s a palace located in the North Star of the Big Dipper.

In any case, I suspect Toriyama’s depiction of souls gathering at a Chinese palace is likely inspired by this Dàoist idea. But what occurs next is from Buddhism.

Judging Cloud-Souls – Enma-dai-ō

As we see in the next panel of the manga, this palace is inhabited by a gigantic man who sits behind a large wooden desk and judges each of the dead. He is Enma-dai-ō (閻魔大王, “Village Gate Demon Great Lord”). In Dragon Ball he is often referred to as Enma-sama (エンマ様, “Lord Enma”).

American DBZ fans of the anime know him as King Yemma. This is a warped pronunciation of his original Indian name of Yamarāja (यमराज), the “King of the Dead” in Hinduism. He’s often called Yama for short, which is believed to mean “twin,” alongside his brother Yami.

Yamarāja is adopted into Buddhism and exported to China where he’s called the Yánluó-wáng (閻羅王, “Village Net King”), which is a partial calque of the Sanskrit of yamarāja. A calque is a word-for-word translation, so this is part of his name translated. His name implies that he filters out those who are not worthy by catching them in his net of judgment. This name then carries over to Japan as Enma-dai-ō, and in-turn, Enma-sama.

When FUNimation dubbed these episodes of the anime in 1997 they called him Yemma instead of Enma or Yama. But I don’t know why. In contrast, they called Shenron ‘Shenlong’ in order to connect him to the Chinese culture that inspired his creation. But here they went with Yemma instead of Yanluo (Chinese), or Yama (Indian). So it’s not Enma, nor Emma, but Yemma, as a cross between cultures. Frankly, it’s just plain wrong. But that’s his name over here all the same.

His character in Dragon Ball is inspired by a character of the same name in Journey to the West, where he is one of 10 judges of the Underworld. In Dragon Ball’s case, there is only one judge, but he performs the same role of judging the dead to decide if they go to Heaven or Hell. In Dragon Ball, if they go to Heaven, they get there by riding an airplane!

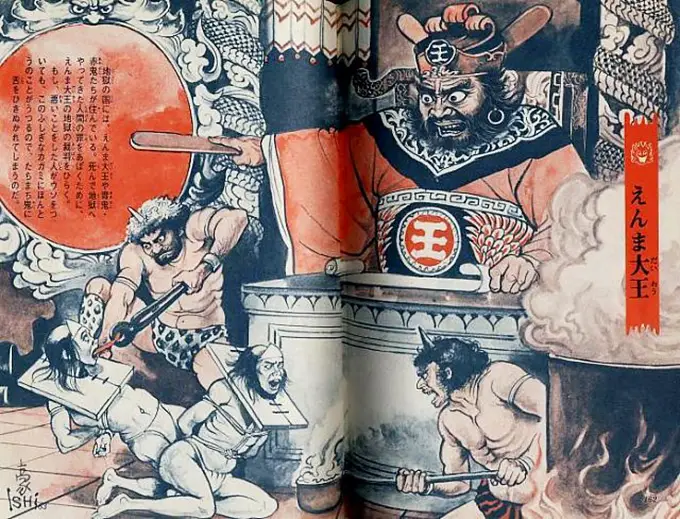

Enma-dai-ō by Kyosai Kawanabe

Enma-dai-ō is portrayed differently depending on which culture you look at. In China he is a combination of ideas from Buddhism that are influenced by Hinduism and mixed with Confucianism, so he is usually portrayed in the classical Chinese robes of a stately official. He is often shown administering punishment to sinners.

Enma-dai-ō by Gojin Ishihara

Toriyama does the opposite of this and dresses him in a modern Western suit. Yet to still convey Enma’s demonic visage, Toriyama gives him a hat with ox horns on it. The kanji of en (閻, “village gate”) is placed in a circle on the front of his hat. This is the first kanji in his name, and also signifies that his job is to manage the gates of the afterlife. He determines which gate a cloud-soul will pass through. It’s also in the same place as the character of ō (王, “king”), which he wears in traditional depictions.

It is Enma’s job to look up the cloud-soul’s identity in his book of the dead, which is inspired by the Buddhist Book of the Dead.

This book is titled the Enma-chō (閻魔帳, “Village Gate Demon Screen”). The book contains a complete record of the sinful and virtuous deeds of every person in existence. When a cloud-soul comes before Enma, he looks at his Enma-chō, reviews their deeds, and judges them accordingly. It’s also referred to as a kiroku (鬼録, “demon book”) or seishibo (生死簿, “life and death list”)

This is similar to Saint Peter in the Christian faith, who stands before the Pearly Gates of the Kingdom of Heaven and decides if a person is worthy of entering Heaven or will be condemned to Hell.

However, the term enma-chō is also common Japanese slang for a notebook carried by a teacher who writes down the grades, attendance, and behavior of a student in order to judge them at the end of the school term. It’s also used by police officers who record everything a suspect does in order to bust them on it later.

So Toriyama’s depiction of Enma using an Enma-chō is something that his young Japanese readers will get a laugh out of. It’s as if Enma is actually looking up their performance in the class of life, and someday will do the same for the young reader.

Another common Japanese expression derived from this Buddhist belief is kiseki (鬼籍, “demon’s ledger”). Like the Enma-chō, it means a book that records the names of the dead, plus their line of ancestry. So In Japanese society, when a person dies, rather than be blunt and use those harsh words, they will refer to it indirectly by saying they’ve had their name added to the kiseki. This may be an evolution of the original Chinese idea that when a person dies, their pò can become a ghost or demon.

Because a person’s entire life is recorded in the book, including their birth, lifespan, and date of death, it means that their lives are fated to end at a certain point. That’s why in Journey to the West, the Monkey King travels to the underworld and scratches out his name and the names of his monkey people from this book. This makes them immortal, because their date of death has been scratched out. As a result of ruining the book, Enma can’t judge the Monkey King or exert his power over him. This leads to the army of Heaven attacking the Monkey King to subdue him.

Enma’s name is written on a name plate placed on the front of his desk, as was common the late-80’s and early ’90’s. From left to right it reads “閻羅大王” (Enma-dai-ō). On the back of the plate it says in English letters, “CLOSED”. This suggests he turns the plate around when he goes to sleep or takes a break (if he ever does). But if that were true, would the cloud-souls have to wait for him to come back to his desk? Like when someone goes to a bank teller and has to wait around?

The last question to ask is the one of where Enma is located. I mentioned the Dàoist concept of location earlier, and in a similar fashion the location of his realm varies in the Buddhism of different countries and across time. In the Buddhism of China, sometimes it’s in the underworld inside a dark cave, or in a palace amid the darkness and behind a large gate. While in the original Buddhism of India, he can be located in a heaven realm called Svarga, which in Chinese is called Tiānshàng (天上, the “heaven above”). This earlier version more closely aligns with Toriyama’s depiction. And of course Toriyama’s depiction has parallels to the aforementioned illusion to the Christian Pearly Gates.

So even though we have seen maps of the Dragon World’s cosmos and the location of Enma’s palace, it’s still unclear where it is located within the universe itself. Or if there is a similar palace and judge in every one of the 12 universes.

Ultimately, in Dragon Ball, the souls travel from This World to the Other world, enter a heavenly afterlife filled with clouds and a Chinese palace, are guided by oni, float through a gate, and are then judged based on their deeds in life, only to receive a halo, be reincarnated, or sentenced to a heavenly or hellish realm. This occurs because Toriyama combines Buddhist, Dàoist, Hindu, Shintō, and Christian ideas into a single scene. This fusion of cultures is what I call Dragon Ball Culture. And this proliferation of religious ideas to hundreds of millions of people across the world is a power unto itself.

Of course, Toriyama does this in his classic lighthearted fashion, as if the scene were a parody of these religious ideas. He’s not trying to promote religious ideas. He does this to entertain his audience. And then to surprise his readers he adds several jokes, flips expectations by combining the traditional and modern, and inverts common depictions of these famous characters and the realms they inhabit.

Cloud-Souls in the Dragon Ball Anime

This single image of the cloud-souls approaching the palace is the only example of souls that appears in the manga. Once Toriyama establishes this idea, it’s implied moving forward that anyone who dies will arrive at the palace in this form. As a result, the anime uses cloud-souls in its filler episodes and films to reinforce this spiritual concept.

The first example is in Dragon Ball Z episode 13, titled “Hands Off! Enma-sama’s Secret Fruit” (Te o Dasu na! Enma-sama no Himitsu no Kudamono, 手を出すな!エンマ様の秘密の果実).

This is the episode when Goku accidentally falls off of Snake Way during his journey to King Kai’s planet, and has to escape from Hell.

While he’s in Hell he is surrounded by cloud-souls who have been sentenced by Enma-sama. But contrary to what you might think, they’re having a fun time. They go on theme park rides and playgrounds, run around like they’re playing a game of tag, and they even go on group hiking trips. And just like we see in their first depiction, they make playful noises to communicate their joy.

During this episode Goku confronts two oni named Gozu and Mezu. They are inspired by two characters from Journey to the West named Ox-head and Horse-face that guard the gates to the underworld.

For more on this episode’s culture, see my article titled Dragon Ball’s Bloody Pond of Hell.

Another major example is in the twelfth Dragon Ball Z film, titled Dragon Ball Z: The Rebirth of Fusion!! Goku and Vegeta!! (Dragon Ball Z: Fukkatsu no Fusion!! Goku to Vegeta!!, ドラゴンボールZ 復活のフュージョン!!悟空とベジータ!!).

In this film, a mistake occurs in the cloud-soul filtration facility. This is a place where the evil energy of souls that is generated while alive is removed from their bodies before they reincarnate or are sent to another realm. Unfortunately a negligent young oni fails to replace a tank that fills up too fast, and all of this evil energy explodes onto him. This creates a demon that takes over the oni’s body, and this demon then overthrows the afterlife and causes countless cloud-souls to return to their original bodies across the universe.

As a result, the dead come back to life! Goku and Vegeta are then called in to save the day and return these cloud-souls to their rightful place by freeing Enma-sama. Meanwhile, on earth, their families fight against the undead, including a revived Hitler!

The cloud-souls also show up in occasional filler content during transitions into other scenes in the afterlife.

Toriyama’s Inspiration for Cloud-Souls

Where did Toriyama receive the inspiration to use cloud-souls in Dragon Ball?

The most likely answer is Journey to the West, the main literary source of inspiration for Dragon Ball. However, I do not recall any depictions of souls appearing as clouds in the story. In addition, Toriyama does not read that often, so if Journey to the West is the source, then it would likely be a TV or cinematic adaptation of the story.

The next most likely answer is kung fu cinema. Toriyama is a big kung fu movie fan. Especially the films of Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan. However, Bruce Lee emphasized realism in his films and avoided the promotion of orthodox religious beliefs, while Jackie Chan celebrated traditional kung fu in his films, but for the most part avoided the supernatural.

This leaves the subgenre of kung fu films known as ‘Spooky Kung Fu.’ This subgenre emphasized the supernatural concepts found in Dàoism and Buddhism, and often featured ghosts, demons, gods, heaven, hell, jiāngshī (Chinese ‘zombie-vampires’), and other paranormal ideas. Jackie Chan’s counterpart, Sammo Hung, was responsible for making this subgenre famous. However, among all of the spooky kung fu films I’ve watched, I have yet to see an example of a person’s soul appearing as a cloud.

So for the time being, where Toriyama received the inspiration for cloud-souls in Dragon Ball remains a mystery. But I will keep looking!

Soulful Conclusion

If you’ve made it this far, then you’ve passed the test and can board the plane to Heaven!

This was a brief look into the traditional culture that inspired the creation of Toriyama’s cloud-soul. But this discussion only scratched the surface of the soul depicted in Dragon Ball, and there are still many questions to answer.

For example, why does Goku get hungry when he’s training in the afterlife if he’s already dead?

What determines if a person goes to Heaven, Hell, a paradise, or reincarnates? What is Enma looking for?

Why do some people get to keep their bodies and receive a halo?

If Majin Buu is evil, why isn’t he sentenced to Hell, and instead reincarnates as Uub?

How does Uranai Baba travel between This World and Other World to hire undead warriors to fight for her?

Why does Vegeta receive a new body at the end of Dragon Ball Z? And on a similar note, in DBZ movie 12, why does Vegeta turn back into a cloud-soul after saving the universe?

Do you have the answers to these and other questions? Or would you like to learn them? Leave your comments below.

' . $comment->comment_content . '

'; } } else { echo 'No comments found.'; }