Cultural Origin of Papparapā!

Papparapā! What is the meaning of this magic word spoken by Babidi in Dragon Ball Z? Until now, it has remained a mystery. Discover the power of papparapā!

Did Akira Toriyama make up this word? Did he find it somewhere else? What secrets does it hold?

Hundreds of millions of Dragon Ball fans have heard this word repeated in each watching of the series, and yet have no idea what it means or where it comes from.

In this article you’ll learn the complete origin of papparapā and find out where Toriyama received his inspiration to include it in Dragon Ball.

This article is an excerpt from my upcoming book, Dragon Ball Language. This book reveals the origin of over 500 names of the people, places, and things in Dragon Ball.

Definition of Papparapā

Papparapā (パッパラパー, ‘pahp-pah-rah-paah’) is a real-life Japanese nonsense-word and magic word that means “nonsense,” “balderdash,” or “gobbledygook.”

Papparapā is used to describe the indescribable, to express shock and awe, to ridicule someone speaking foolishly, and to activate magic. In this final sense it is similar to the Western words of hocus-pocus and alakazam.

Toriyama’s use of papparapā as a magic word aligns with the magical theme of the Majin Bū arc of Dragon Ball. Toriyama places it alongside the other magic words used for the names of Puipui, Dābura, Yakon, Bibidi, Babidi, and Bū.

I’ll explain these names in future articles and in Dragon Ball Language.

Papparapā is a Magic Word

The magic word of abracadabra, which is to be read with one less letter each time.

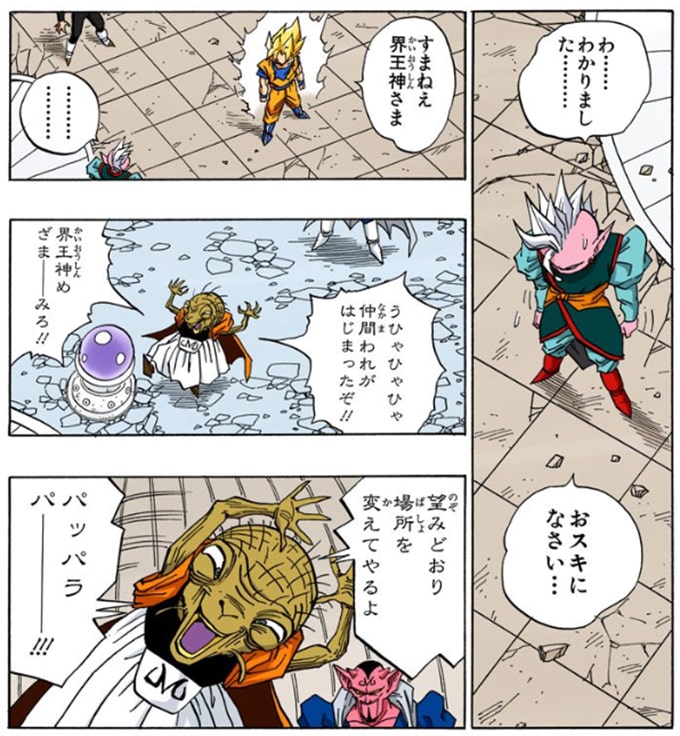

Papparapā is a magic word spoken by madōshi-Babidi and his father madōshi-Bibidi in Dragon Ball. A madōshi (魔道師, “magic-way-master”) refers to an expert in the dark and occult arts of magic spells and wizardry.

These wizards say papparapā each time they cast their spells, such as before teleportation, spirit possession, and seering with a crystal ball. The final elongated pā (パー) sound is spoken in unison with the activation of the spell’s effect, and it often coincides with a sudden hand motion.

What is a magic word?

According to the book Magic Words: A Dictionary (2008), by Craig Conley, “Magic words are words spoken with a special reverence for the Mystery—those enigmatic words and phrases, not usually employed in everday discourse or conversation, which invoke the powers of creation and destruction when something is to appear out of thin air or to disappear back into the great void. Too often dismissed as ‘meaningless gibberish,’ such magic words are, on the contrary, rich in meaning for those initiated into their significance.”

Magic words are found in every culture across the world. Toriyama uses different magic words for different characters in the series, depending on whether they are Eastern or Western (and alien) characters.

Papparapā in Dragon Ball

The first time Babidi uses papparapā as a magic word to enact his magic spells in Dragon Ball is when Babidi teleports his subordinate Puipui and his opponents to Puipui’s alien planet within the confines of his spaceship. The divine Kai-ō-shin then explains that it must be Babidi’s evil magic at work.

Babidi then goes on to use this same spell four more times. Once for Yakon’s battle with Son Gokū. The other with Dābura’s battle with Son Gohan, where he transports them to what appears to be a Demon Realm. Then once more to transport everyone to the Tenkaichi Budōkai stage. Finally, to a wasteland for Vegeta and Gokū to fight it out.

As the series goes on, Babidi uses it for magical offensive and defensive techniques. For example, covering Pikkoro with an electric slime that will make his body explode. And for creating an energy barrier around himself to defend from attacks.

Etymology of Papparapā

The etymology (‘origin and history’) of papparapā has not been well-researched and there are no definitive works to cite on the topic. As a result, I’ve invested a great deal of effort to uncover the lost pieces and put them back in place to reveal its etymology. This article represents the first time the etymology of papparapā will be fully explained.

According to my research, the most likely source for the origin of the Japanese word papparapā is the German word papperlapapp (“nonsense,” “balderdash,” “poppycock,” “hogwash,” “pish-posh,” or “rubbish”). Papperlapapp is used to ridicule someone speaking foolishly. This remains one of its uses in Japanese, creating a direct line between the two.

I am uncertain on the date when this foreign loan word entered the Japanese lexicon. But just like other foreign loan words exported to Japan, papperlapapp was localized in katakana, as pappārappu (パッパーラップ). It remains unclear how pappārappu changed over time to papparapā, but spelling differences are moot in this case because the word is nonsense to begin with and the usage of the word remains the same.

Toriyama did not coin the word papparapā in Japanese and he was not the first to use it. The use of papparapā extends at least as far back as 1967 when it was spoken in the Japanese adaptation of an American children’s cartoon.

Papparapā in Shazzan

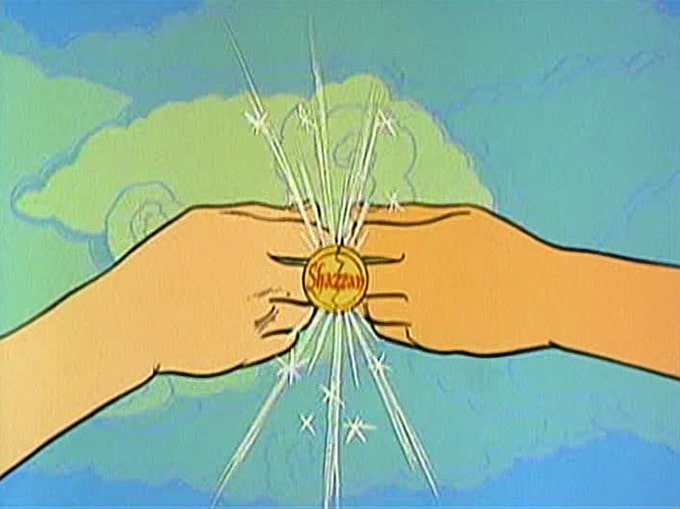

In the Saturday morning cartoon called Shazzan (1967)[1], the titular character of Shazzan is an all-powerful genie living in “the magical land of the Arabian Nights.” A pair of American twins named Chuck and Nancy discover two mysterious rings in a cave off the coast of Maine. Each ring has one half of the word “Shazzan” written on it, and when the rings are joined together the twins are sent 1,000 years back in time to Arabia.

Once there, the twins meet Shazzan, who is bound to the ring. Shazzan gives them a magical flying camel named Kaboobie and tells them to bring the ring back to its rightful owner, a great wizard. He then says he will use his magic to help the twins on their journey, such as by defeating monsters and wizards who seek the ring.

The Japanese adaptation of Shazzan is titled Daima-ō Shazān (大魔王シャザーン, “Great Magical King Shazān,” January 12, 1968—March 29, 1968).

Thanks to a forum post by a leading Dragon Ball fan screen-named “Herms,” written in 2008 on his co-owned website, Kanzenshuu.com,[2] I learned that in Daima-ō Shazān the genie shouts “Papparapā” before he casts magic. He does not do this in the English edition.[3] Herms paraphrases his discovery of this revelation on the Japanese Wikipedia article for the show. [4] Unfortunately, this Wikipedia article does not cite any sources for this claim, and Herms could not find any examples of the Japanese show to confirm the claim either, so it remained hearsay for the last 11 years.

The Wikipedia article for Shazān also says that during its first broadcast in 1967, “… papparapā became a buzzword among children.” If true, then in theory this could be where Toriyama first learned of papparapā.

Since there were no sources for either of these claims, I took it upon myself to rediscover the origin of papparapā in an attempt to prove or disprove the claims.

Shazān in Japan

Having completed my research, I can now confirm that Shazān was indeed a popular show with children in Japan during the late-1960s and early-‘70s, and then again over the following decades via sporadic reruns on the Japanese Cartoon Network.

Above is the Japanese introduction for Daima-ō Shazān that children were fond of. You can also listen to the extended version, which I believe is from the official album.

Akira Toriyama was born on April 5, 1955, so he would have been 12 years old when Shazān first aired in Japan. Given that Toriyama was, in his own words, “raised on TV,” as I describe in my book Dragon Ball Culture Volume 1, and given the hundreds of TV and film-based references in Dragon Ball, it is likely that Toriyama saw Shazān and became familiar with the papparapā buzzword among his peers at school.

Many Japanese adults today have nostalgia for Daima-ō Shazān, and several have shared their thoughts on personal blogs.

Why did they like Shazān? One Japanese blogger said Shazān stood out from Japanese anime of the time because it was produced in America with a different art style and colors than children were used to seeing. He said it had a cool introduction song that felt ‘Arabic’ and exciting.[5]

Another blogger found the heroes appealing because they were adults, rather than kids, as was most common in Japanese shōnen (“young boys”) anime; so the heroes were strong instead of thin, and smart and sophisticated compared to naïve boys.[6]

In general, Shazān introduced Arabian’naito (アラビアンナイト, “Arabian Nights”) culture to a young Japanese audience. Once this culture proved successful, the popularity of Shazān led to a native Japanese gag-anime spin-off for kids called Hakushon Daima-ō (ハクション大魔王, literally “Achoo! Great Magical King,” 1969), which is about a genie who is summoned from his lamp whenever his young master sneezes.[7]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4czzfxfzy6o

Papparapā Buzzwords

The buzzwords of ‘Detekoi Shazān,’ ‘haihaisā,’ and ‘papparapā‘

Papparapā is one of three buzzwords Shazān created among Japanese children. A buzzword is, “A word or phrase, new or already existing, that becomes very popular for a period of time.”

The second buzzword is, “Detekoi, Shazān!” (出てこい、シャザーン!, “Come out, Shazān!”). This is spoken by the twins when they summon Shazān using their magic rings.

Astute Dragon Ball fans may recall Pikkoro-daima-ō (ピッコロ大魔王, “Great Demon King Piccolo”) saying a similar expression when he summons Shenron with the dragon balls and says, “Detekoi, Shenron, to yara yo!! (出てこい 神龍とやらよ!!, “Come out, Shenron (if you will)!!”).

One is for a wish-granting genie, the other a wish-granting dragon. Perhaps this was Toriyama paying homage to this call-to-action for a magical being, as remembered from his childhood.

As a side note, daima-ō (大魔王) can mean both “great demon king” and “great magic king.” The latter form is another way of referring to a genie.

The third buzzword is “Haihaisā!” (ハイハイサー!, “Aye aye, sir!”).[8] This is spoken by Shazān when he responds to the twins’ requests.

The reason Shazān says haihaisā is because in the Japanese edition of the series the producers changed his personality to be more subservient to the twins then in the American edition—where he instead shows up, saves the day, and leaves.[9] In the Japanese edition Shazān has a childlike personality and follows the more common trope of a genie being a servant to their master, ala the classic genie from Aladdin’s magic lamp.

However, Japanese kids were not familiar with the meaning and origin of this foreign expression rooted in Western naval traditions, so when Shazān said haihaisā they thought he was speaking an Arabic nonsense-word. So then they started saying “haihaisā!” to one another as a buzzword, along with “papparapā!” and “detekoi, Shazān!”

The basic flow of the show progressed as follows. The twins would get into a dire situation, join their magic rings and shout, “Detekoi, Shazān!” Then Shazān would appear, laugh: “Oh ho ho, ho ho ho ho ho!”, and say, “Haihaisā, goshujin-sama.” (ハイハイサー、ご主人様, “Aye aye sir, my masters.”). Then he’d say “Papparapā!” and cast his magic.[10]

These three things happened in each story, and there were two stories in each broadcasted episode, so these phrases were heard many times by children. From this, one could conjecture that as a result of the show’s popularity, children were saying these phrases when playing with friends as they cast their imaginary magic.

Japanese adults still say these three buzzwords out of nostalgia.[11] In fact, some people only remember these buzzwords from their childhood without remembering the name of the show.[12] I found one man who remembers watching Shazān during elementary school, but misremembered the name of the show as, “Detekoi, Shazān!”[13]

These buzzwords were so popular that they’re still used to sell the series today.[14] For example, watch the 2:22 mark in this video to see all three of Shazān’s catchphrases spoken in Japanese back-to-back by a narrator of a commercial to sell the show.[15] There are more examples at 4:02:

Proof of Papparapā

The intro and commercial videos of Shazān are useful for describing the above background information, but I really wanted to watch Shazān himself say papparapā because that’s the only way to determine if he says it in the show, and if Toriyama was influenced by the show.

After several days of searching, I found a single clip from Shazān where we can see and hear dozens of examples of Shazān saying papparapā. It happens to be a silly edit by a NicoVideo user that features a papparapā marathon half-way through:

Despite the silliness, in this clip we find all three buzzwords being used. We also witness similarities between how Shazān, Bibidi, and Babidi say papparapā, where it is spoken quickly, with force, and with an extended ‘pā’ sound at the moment of activating the magic. This often coincides with dramatic movements of the hands.

Pā Power!

The ‘pa’ sound is emphasized in the show Ike! Gurīnman

Whenever Babidi casts a spell, he shouts the final ‘pā!’ at the end of papparapā, as if he’s saying “pappara-pā!” And it as this moment when the spell is activated.

Toriyama uses this same emphasis with the dodonpa technique used by Tao Paipai, Tenshinhan, and Chaozu, where they fire the beam at the moment of shouting ‘pa!’ Likewise Gokū’s kamehameha, where he fires the beam at the moment of shouting ‘ha!’ Each of these coincides with their hands thrusting toward their opponents.

Why does Toriyama do this? Toriyama and the anime voice actors have never provided an explanation, but I surmise there are two reasons for it.

The first reason is to emphasize the active moment of the spell. The way these words are spoken in Dragon Ball is similar to how Western magicians say the equivalent magic words of hocus-pocus, abracadabra, and alakazam when they emphasize the ‘po’ in pocus, the ‘dab’ in abracadabra, and the ‘zam’ in alakazam. Such emphasis coincides with a hand motion, snapping of the fingers, or pulling away of a dark sheet to ‘activate’ the magic.

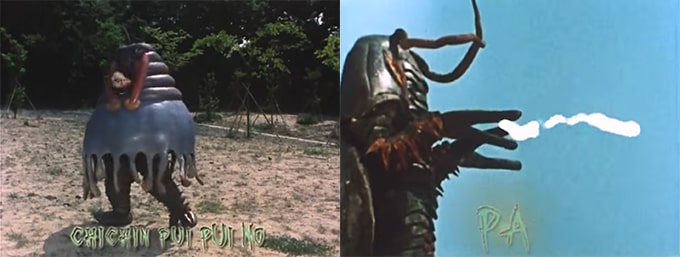

The second reason is that Toriyama may have seen this done in a children’s tokusatsu show such as Ike! Gurīnman (行け! グリーンマン, “Go! Greenman,” November 12, 1973—September 27, 1974). This TV show is produced by Toho and is a low-budget live-action series, similar to Gojira, but lighthearted.

In this show, the main villain, the Ma-ō (魔王, “Demon King”), casts his magic, chanting “Adara Mudara… Pa!”

His minion does the same thing when he chants the magic phrase of chichin puipui and then ends it with a ‘pa’!

Toriyama and Arabian Nights

Akira Toriyama interview in Shonen Jump magazine, translated on Kanzenshuu.com

Akira Toriyama was exposed to ‘Arabian Nights’ culture as a child, and he had Arabic culture in mind when creating the Majin Bū arc.

We know this because Toriyama is asked about his inspiration for Majin Bū in his American Shonen Jump interview in 2007.[16] The staff ask, “Is the appearance of Majin Bū inspired by the Arabian-style majin, or ‘genie’? His clothes seem to have a sort of Arabian fairy-tale style. Or were you thinking of a different kind of ‘majin’? Toriyama says:

“Right. I saw The Arabian Nights when I was a kid, so I have this set image of what a majin, or genie, should look like. So that’s how I came to put him in that costume.”

There are many similarities between Shazān and Dragon Ball and general ‘Arabian Nights’ culture that I will discuss in detail in a future book titled Dragon Ball Z Culture.

I cite the above quote to prove the thesis of this article, which is that from the information provided to you in this article it is logical to infer the following conclusions:

- Toriyama is exposed to the Arabian Nights mythos as a child and uses it as inspiration for his characters and parts of the story of the Majin Bū arc.

- The source of Toriyama’s inspiration for Babidi shouting papparapā as he casts magic is inspired by Shazān doing the same thing in Daima-ō Shazān.

- The popularity of papparapā among children during Toriyama’s youth, combined with Toriyama’s exposure to Arabian Nights mythos and genie-type characters, caused Toriyama to recall this period of time from his youth and add it to Dragon Ball.

This cause-and-effect relationship in the content depicted in Dragon Ball follows the trend of Toriyama referencing his childhood memories when coming up with ideas for Dragon Ball.

When he needs to come up with new ideas to meet his editor’s deadlines, he thinks back on his own life of watching television and movies, remembers things from his childhood, and then adds them into the series without telling anyone.

There are countless examples, from references to Kamen Raidā, Urutoraman, Gojira, samurai films, and sūpā sentai series, to childish games of rock-paper-scissors and pinky swears.

Like Magic!

Just like magic, now you know what papparapā means.

The truth is that papparapā means “nothing,” yet it can do anything, and millions of people have been saying it for decades without realizing it.

This article took over 200 hours of effort to research, write, and publish. Please share it with your friends and continue to support my writing by buying my Dragon Ball books.

Speaking of papparapā, check out my follow-up article, Popular Forms of Papparapā, where you will learn the other ways papparapā is used in modern Japan and across the world!

Footnotes and Resources

[1] Shazzan (1967) is a children’s animated series made by Hanna-Barbera Productions, Inc. (founded 1957) and broadcast on CBS in the United States. In Japan it was broadcast on NET (currently TV Asahi). Shazān aired Every Monday and Friday evening at 7 pm alongside popular anime of the time, such as Saibōgu 009 (サイボーグ009, “Cyborg 009,” April 5, 1968—September 27, 1968), which increased its likelihood of being watched by children.

[2] Post on Kanzenshuu by Herms titled “Origin of Babidi’s chant

.”[3] In the original English edition of Shazzan, he laughs, “Oh ho ho, ho ho ho ho ho!” before casting magic.

[4] Shazān on Japanese Wikipedia, and the Japanese AtWiki.

[5] Quote about how the Shazān theme song felt cool and ‘Arabic’: http://goinkyo.blog2.fc2.com/blog-entry-146.html

[6] Quote about how Shazān had strong, smart, and adult Western heroes, compared to Japanese shōnen heroes: https://blog.goo.ne.jp/banbo1706/e/38e11d473f9e7f29b00ccddb9eee013c

[7] The daima-ō (大魔王) in Daima-ō Shazān (大魔王シャザーン, “Great Magical King Shazān”) is translated as “Great Demon King” when referring to Pikkoro-daima-ō in Dragon Ball. But the kanji of ma (魔) can also mean “magical.” So in this case, daima-ō refers to a “genie.” I’m not certain if this is a common practice outside of children’s cartoons, as I have only encountered instances of this in children’s cartoons such as Shazān and Hakushon.

[8] The foreign expression “aye aye, sir” originates in the British Royal Navy, circa the late 16th and early 17th century. “Aye” was the formal word for voting “yes” in the United Kingdom House of Commons. The word then came to be used in the Navy as a way to distinguish between agreement to a statement, as in ‘yes, you are correct,’ and as a way for a junior seaman to confirm to their commanding officer that, ‘I under-stand your order and will follow it.’ “Aye aye, sir” was then adopted by the United States Navy. From there, I surmise it became a foreign loan word expression in Japan via the interaction of these two Navy’s with Japan in the following centuries.

Etymology of “Aye aye, sir.”: Wikipedia for aye aye, sir, and Wiktionary for aye aye, sir.

Haihaisā in Japan: quicktranslate.com.

[9] Shazān is more subservient in the Japanese edition of the series than the original English version: Japanese Wikipedia for Shazān

[10] Flow of events in Shazān: http://animenomori.sblo.jp/article/45745184.html

[11] Examples of Japanese adults saying phrases from Shazān that they remember from childhood: https://detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp/qa/question_detail/q14190329, https://blog.djf.jpn.com/?p=9988, https://sakuhindb.com/janime/7_SHAZZAN_21/, http://iblog.atclip.com/?eid=1216625, https://detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp/qa/question_detail/q13178332263, https://www.quicktranslate.com, https://chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp/tag/tags.php?tag=%E3%83%8F%E3%82%A4%E3%83%8F%E3%82%A4%E3%82%B5%E3%83%BC

[12] Japanese fans of Shazān remembering the buzzwords from their childhood, but not the name of the show: https://detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp/qa/question_detail/q1456728334

[13] More fans not remembering the title, only the buzzwords: https://ameblo.jp/45yshiken/entry-12359850127.html

[14] Promotional video for American cartoons being sold in Japan, including Shazān: https://www.nicovideo.jp/watch/sm28742471

[15] Additional YouTube copy of the Japanese commercial to sell Shazān and other cartoons, in case the NicoVideo video goes down: YouTube

[16] Kanzenshuu Translation of Shonen Jump Interview with Akira Toriyama

Leave a Reply